Peter Kinderman is Professor of Clinical Psychology in the University’s Institute of Psychology, Health and Society and President of the British Psychological Society:

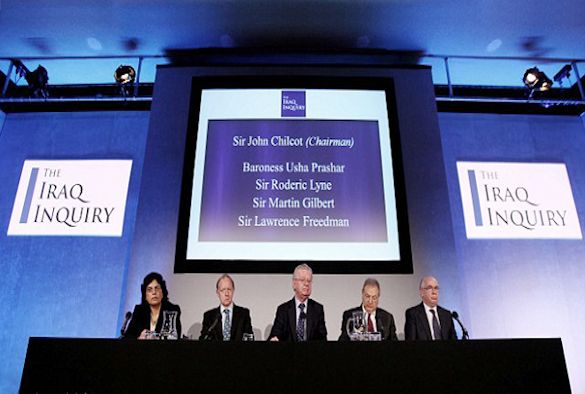

“The Chilcot Report into the decision to go to war in Iraq has highlighted the irrationality and psychological vulnerability of our leaders, and how disastrous the consequences can be.

As the fall-out from the EU Referendum left us painfully aware, there are dangers in making decisions under conditions of high emotion, poor quality information and great uncertainty. Coming so soon after Brexit, we are even more acutely aware of the limitations of our politicians.

Sadly, we have become to expect that politicians will act in their own best interests, avoid direct answers and backtrack on their promises. But I had hoped senior civil servants, military commanders and, crucially, the shadowy chiefs of our intelligence services would take the most rational approach to the process of decision-making.

But the Chilcot Report shows that decisions – life-and–death, world-changing decisions – fell prey the same disastrous cognitive biases to which we are all prone.

Psychologists have always known that human beings are irrational. The philosopher and proto-scientist, Roger Bacon suggested in 1266 that a principal source of error was our “false conceit of our own wisdom”.

We find it difficult to retain more than a few relevant facts so use rules of thumb – heuristic reasoning – rather than cool logic. Our decisions are distorted by emotions, by the most memorable information, by irrelevancies and by other people. We seek out information that confirms rather than challenges our assumptions. And we seek the company of people who agree with us.

Once a decision has been made, we naturally feel terrible at the thought that we may have made mistakes. The phenomenon of ‘cognitive dissonance’ – and the psychological discomfort it causes – means that we sometimes try to change the facts to make ourselves feel better. Chilcot said Tony Blair had presented intelligence about Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction “with a certainty that was not justified”.

We are cooperative animals. Cooperation has been and remains crucial for our survival. But the nature of human groups means that we form alliances and support our friends in ways that are not always in the best interests of anyone. Political alliances may be of short-term benefit of politicians, but may not always serve the interests of citizens.

But what of irrationality, what of an understanding of flawed human psychology, in this mess? These flaws in human reasoning and in our human relationships all applied in the run-up to the fatal decision on Iraq. Individuals will be blamed, but it’s important that we also understand that psychological biases were at play and to make the necessary changes to legal, constitutional and political processes to improve the quality of decision making and prevent future mistakes.

As with the EU referendum, we should let the lawyers, politicians and civil servants do their jobs. We should actively inform and advise leaders of civil society as they sort out the mess in which we find ourselves. We can offer advice as to how we choose our leaders, form our groups and make our decisions. Above all, we need to choose and select people free, as much as possible, from the conceit of false wisdom.”

well said. A life time of politicians acting through emotion and not logic

would robots do any better????