Dr Mike Jones is a Lecturer in the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Popular Music, part of the Department of Music

I was 14 at the time of the Aberfan disaster and I retain strong recollections both of the day and of the following weeks. The strongest of these is one of hush, not so much silence but a generalised restraint.

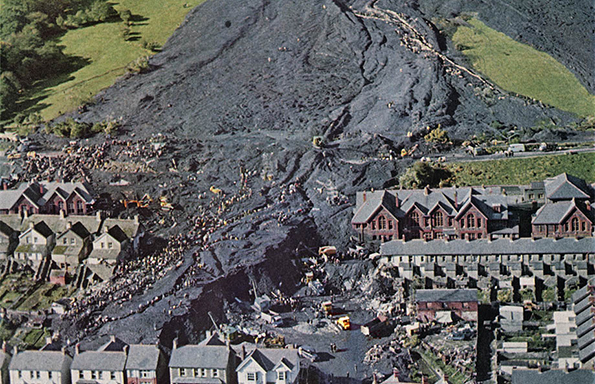

In the evening of the disaster, a police officer called at our house (in Rassau, 12 miles from Aberfan). He asked how many able-bodied men lived at the address. I was too young to be so considered, but my father fell easily into this category and he was instructed to collect his garden spade, put out on his wellingtons and warm clothing and to await further instruction. That ‘further instruction’ never came, but he sat up all night waiting for it. This call for ‘diggers’ at such a wide radius conveys something of the scale of the disaster, and that ‘hush’, that ‘restraint’, conveys some sense of what was then a shared culture and a shared experience that has dissipated in the 50 years since the avalanche of slurry destroyed the Pantglas Junior School.

On the eve of the World War One, there were 250,000 men underground in South Wales. In the 1960s, almost all working class families in South Wales derived from that enormous influx of men into what formerly had been remote, rural valleys. Mining was a shared and general back-drop to existence, but ‘existence’ is the pivotal term here: coal mining is an inherently dangerous occupation, for example, in 1913 at Senghenydd, nine miles south of Aberfan, 439 miners died in an underground explosion. Premature death, whether this way, by accident, or by the constant breathing of coal dust miles from fresh air, constantly problematized the lives of a family’s ‘bread-winners’. And there was little ‘bread’ to be won, certainly until the nationalisation of coal in the wake of World War Two. So it was that mining families might also be very poor families and ones exposed always to the exigencies of fluctuations in demand and therefore in employment and income. In its turn, these shared experiences translated into a shared culture across the Western and Eastern Valleys.

As it transpired, ‘fluctuations’ were severe: what broke the back of coal mining as an industry was the end of steam-powered navies (Royal and Merchant). Demand for domestic coal persisted and what proved to be an essentially temporary boost in demand was generated by the ‘artificial’ revival of the steel industry in South Wales but when the railways switched quite abruptly away from steam and towards diesel power and electrification, the ‘writing was on the wall’ for coal-mining. Even so, as Aberfan showed so horribly, a further threat to existence persisted in the form of the ‘tips’ that were, almost literally, everywhere throughout the coal-mining valleys.

As a child I had no idea that the landscape in which I lived and played was, substantially, a man-made one; because they are so steeply-sided, the valleys exude a strong, natural authority – you can’t see over ‘the mountain’ and journeys to and from other towns and the Welsh coastal cities were slow affairs, as if the landscape begrudged your movement through it. But all of those steep mountain sides were heaped with tips thrown up as the pits were being dug.

Because they were largely historic and had, through time, been largely grassed over, they seemed only to be a feature of the landscape, but as Pantglas demonstrated so cruelly, those tips had been amassed over many, many years and then left there with little or no care or subsequent supervision.

When it became known that a school had been swept away in an avalanche of sodden spoil, the response was an immediate and collective one. The emotional response was also a shared one and it manifested as that ‘hush’, I remember. I am not sure how long this lasted or when, and how long after the catastrophe, life returned to normal. At least one school in my home town of Ebbw Vale closed permanently because it, too, was threatened in a similar manner, and this may have been the case in other towns. Certainly, two enormous slag heaps generated by the steel-works were cleared and used as ‘hard-core’ in the construction of the M6 motorway (and this was an operation that took several years to complete such was their alpine scale). In these ways the Welsh landscape was sanitized rather than ‘improved’ and all this work seemed to be carried with a rightful and justifiable sense of shame, as if an impossibly splintered ‘stable door’ was being bolted long after the worst of its horses has fled and trampled the immediate area in the most ghastly and destructive ways imaginable.

In a culture in which it was recognised that coal-mining was a lethal business, no-one had anticipated that it could reach out of history and continue to bring its grief to the communities created around pits. Aberfan is a tale of waste – colliery waste lay waste to the lives of 116 children and 28 adults. Remembering that it did still does not seem quite enough.