Scientists have discovered a new mechanism of how living organisms – including humans – avoid poisoning from carbon monoxide generated by natural cell processes.

Carbon monoxide is a toxic gas that can prove fatal at high concentrations; the gas is most commonly associated with faulty domestic heating systems and car fumes, and is often referred to as ‘the silent killer’.

But carbon monoxide – chemical symbol CO – is also produced within our bodies through the normal activity of cells. Scientists have long wondered how organisms manage to control this internal carbon monoxide production so that it does no harm.

University of Liverpool researchers, working with colleagues at the University of Manchester and Eastern Oregon University, have now identified the mechanism whereby cells protect themselves from the toxic effects of the gas at these lower concentrations.

Carbon monoxide molecules should be able to readily bind with protein molecules found in blood cells, known as haemproteins. When they do, for instance during high concentration exposure from inhaling, they impair normal cellular functions, such as oxygen transportation, cell signaling and energy conversion. It is this that causes the fatal effects of carbon monoxide poisoning.

The haemproteins provide an ideal ‘fit’ for the CO molecules, like a hand fitting a glove, so the natural production of the gas, even at low concentrations, should in theory bind to the haemproteins and poison the organism, except it doesn’t.

Professor Samar Hasnain, from the University’s Institute of Integrative Biology, said: “Toxic carbon monoxide is generated naturally by chemical metabolic reactions in cells but we have shown how organisms avoid poisoning by these low concentrations of ‘natural’ carbon monoxide.

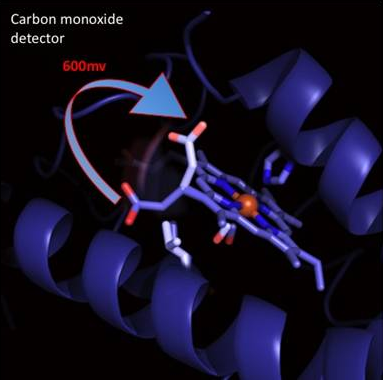

“Our work identifies a mechanism by which haemproteins are protected from carbon monoxide poisoning at low, physiological concentrations of the gas. Working with a simple, bacterial haemprotein, we were able to show that when the haemprotein ‘senses’ the toxic gas is being produced within the cell, it changes its structure through a burst of energy and the carbon monoxide molecule struggles to bind with it at these low concentrations.

“This mechanism of linking the CO binding process to a highly unfavourable energetic change in the haemprotein’s structure provides an elegant means by which organisms avoid being poisoned by carbon monoxide derived from natural metabolic processes. Similar mechanisms of coupling the energetic structural change with gas release may have broad implications for the functioning of a wide variety of haemprotein systems. Haemproteins, for example, bind other gas molecules, including oxygen and nitric oxide. Binding of these gases to haemproteins is important in the natural functions of the cell.”

Lead researcher Dr Svetlana Antonyuk, also based at the Institute of Integrative Biology, said: “We were surprised to discover that haemproteins could have a simple mechanism involving unfavourable energetic changes in structure to prevent carbon monoxide binding. Without this structural change carbon monoxide would bind to the haemoprotein almost a million times more tightly, which would prevent the natural cellular function of the haemprotein and any organism to survive.”

The work has the potential for the use of haem-based sensors for gas sensing in a wide range of biotechnological applications. Sensors, for example, could be used to monitor gas concentrations in industrial manufacturing processes or biomedical gas sensors, where accurate control of gas concentration is critical.

The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

It’s quite an interesting study about carbon monoxide, but there are similar cases of how animals and humans differently deal with internally produced substances and the same substances from an external source. Still, good reading though.