Dr Stephen Royle: “This research is another step towards fully understanding the complexities of the human brain.”

Scientists at the University of Liverpool have found that a protein produced by a gene identified in fruitflies, is responsible for communication between nerve cells in the brain.

The ‘stoned’ gene was discovered in fruitflies by scientists in the 1970s. When this gene was mutated, the flies had problems walking and flying, giving rise to the term ‘stoned’ gene. The same gene was found in mammals some years later, but until now scientists have not known precisely what this gene is responsible for and why it causes problems with physical functions when it mutates.

‘Packets of chemicals’

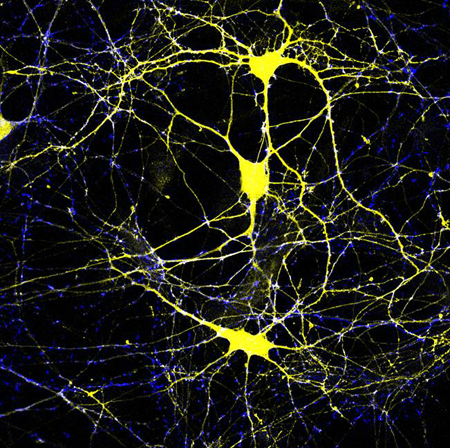

Scientists at Liverpool have found that the protein the gene expresses in mammals, called stonin2, is responsible for retrieving ‘packets’ of chemicals that nerve cells in the brain release in order to communicate with each other. The inability of the gene to express this protein in the fruitfly study, suggests why the insect appeared not to be able to walk or fly normally.

The team used advanced techniques to inactivate stonin2 for short and long periods of time in animal cells grown in the laboratory. The cells used where from an area of the brain associated with learning and memory. They showed that without stonin2 the nerve cells could not retrieve the ‘packets’ needed to transport the chemicals required for communications between nerve cells.

“We have shown that a protein called stonin 2 is needed for the packets to be retrieved. There is currently no evidence to suggest that the gene which expresses this protein is mutated in human disease, but any failure in its function would be disastrous. The research is another step towards fully understanding the complexities of the human brain.”

The research is published in the journal, Current Biology.