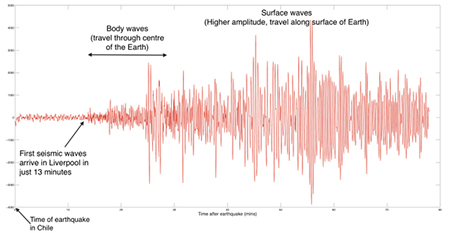

The impact of the Chilean earthquake was felt in Liverpool, as recorded by the University’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Ecological Sciences

The impact of the Chilean earthquake was felt in Liverpool, as recorded by the University’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Ecological Sciences

Andreas Rietbrock is Professor of Geophysics in the University’s School of Environmental Sciences

“Tuesday’s magnitude 8.2 earthquake in northern Chile occurred in an area that scientists had classified as an area of high seismic and tsunami hazard, with the potential for a large megathrust earthquake – the so-called North Chile seismic gap.

“This area of the Andean subduction zone has not experienced any large earthquake since the 1877 magnitude 8.6 quake, which also triggered a large tsunami.

“Subduction zones are the focus of Earth’s largest earthquakes. In these zones, oceanic plate is thrust beneath an overriding plate. In the north of Chile, the oceanic Nazca plate is currently subducting beneath the South American continent at a rate of approximately 66 mm per year.

“In the last two decades, detailed geodetic imaging techniques have been developed, which now makes it possible to directly monitor the build-up of deformation associated with plate movement. Seismology is also used to keep track of earthquake activity deep below the surface.

“The recent North Chile earthquake will provide us with new insights into how earthquakes operate and the physical properties of the plate interface. We are currently exploring possibilities to install seismic stations in the rupture area to monitor the on-going activity.”

Hi David,

You are right, Chile can provide a lot of lessons of earthquake hazard preparedness to other developing countries. Chile is one of the most seismically active regions on the planet, so it has a good reason to be prepared and conservative with its warnings.

In 2010, Chile was struck by a magnitude 8.8 earthquake – the 6th largest earthquake ever recorded on Earth. The shaking from the earthquake took few lives. However, hundreds were killed by the subsequent tsunami. Whilst a tsunami warning system was in place, the warning was incorrectly cancelled and many unfortunately returned to their homes and lost their lives.

Chile has learnt a lot of lessons from 2010 and has now made big steps to revamp its tsunami warning system. Fortunately, in the case of April’s M8.2 earthquake it looks like these changes have taken effect.

Stephen Hicks

PhD student in Seismology at the University of Liverpool

Thank you, Stephen. Obviously you know about this and therefore I would like to ask your views about two possible implications. First, better prevention is not just a one-off purchase. Some of the new expenditure needs to be permanent. The government has very ambitious reform plans (costing about 3% of GDP in higher taxes). Are earthwquake and tsunami prevention among their top priorities? Second, why is Chile in this respect so different from what we usually associate with the rest of Latin America? Maybe these questions should be part of related research programmes, which possibly we at UoL are in a good position to contribute to (maybe jointly with colleagues in Chilean universities)?

Lessons from the Chilean earthquake

A long time ago, someone suggested that possibly the most boring title ever for a news item was ‘Small earthquake in Chile: Not many dead’. The equivalent for the recent (April 1st) earthquake would be ‘BIG earthquake in Chile: Not many dead’. But there is nothing boring this time. On the contrary, a fascinating question has been raised. Why only seven people died? Although there is a large variance, typically earthquakes this strong and the following tsunamis tend to kill hundreds, or even thousands. How did a Richter 8.2 earthquake, only 60 miles away from two coastal cities of 200,000 people each, followed by an admittedly moderate tsunami (but still with seven-feet high waves) and many aftershocks including a Richter 7.6 one striking 27 hours later, exactly at midnight, this time only 12 miles away from one of the two cities, spared human life in such a spectacular way?

The answer offers two important lessons. First, institutional quality: the relevant institutions in Chile have been traditionally good, and recently they have been getting better. This includes anti-seismic building regulations, tsunami alerts, and population preparedness. The building codes are very strict, and they are enforced. Only one high-rise building collapsed in the previous earthquake in 2010 (Richter 8.8), and the respective chief design engineer and several executives were punished with severe civil and criminal penalties. A comprehensive tsunami early warning system has been installed, using the latest satellite and other technologies (developed by Israeli company eVigilo). People receive tsunami alerts in every possible way, via radio and TV, their mobile phones, the internet, road signs and sirens. Chileans have been massively trained, including schoolchildren in exposed areas. Evacuation drills mobilised 500,000 people in Valparaiso in May 2012, and over 100,000 people in Iquique (one of the two cities previously mentioned) in March 2014. When the earthquake actually happened, almost one million people were evacuated.

The second lesson is that there was no populism, because there was no room for populism. There was no gap between what was technically the best solution, and what people wanted (or what opportunistic politicians could misleadingly offer voters). This was by chance rather than design. There was no disagreement regarding the use of scarce resources. The cost of anti-seismic regulations is met by construction companies and home buyers and tenants. The investment in tsunami-warning technologies had already been paid for by the previous government. Ordinary people wanted better protection, and politicians obliged. This absence of conflict between the best policy and any populist alternatives was fortunate.

These lessons in dealing with natural disasters and their consequences apply not only to earthquakes or to Chile, but much more widely.