Figure 1

By Costas Milas, Professor of Financial Economics in the University of Liverpool’s School of Management.

“Less information is more. Sadly, this also applies to the Bank of England’s (BoE) Inflation Report.”

A piece earlier this week by Chris Giles (the influential editor of The Financial Times) uses rather strong language to conclude that the “BoE is talking nonsense”.

The reason has to do with the data series monitored by the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) in order to judge inflation risks and consequently, decide on the appropriate timing of raising the main policy interest rate.

This is indeed an important decision to make because a premature interest rate hike will add unnecessarily early to the costs of borrowing for individuals (through, for instance, mortgages payments) and companies which in turn will slow down the momentum of economic growth and revert the recent fall in unemployment.

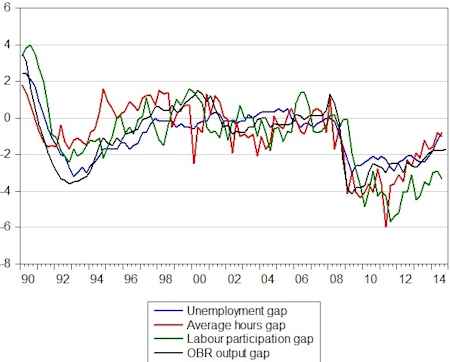

Figure 1 plots, over the 1990-2014 period, three measures of “labour market slack” used by the Bank of England.

These are Bank of England estimates of the unemployment gap, the labour participation gap and the average hours gap.

All three measures represent economic slack indicators: the higher their value, the closer the economy operates to full capacity and therefore, the higher the risk of inflation and the need to act rapidly by raising the policy interest rate.

Figure 1 also plots the output gap estimate of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) which provides independent and authoritative economic advice to George Osborne, the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

The output gap provides an (alternative) estimate of how the economy does with respect to its potential and can be thought of as a “competitor” of the Bank’s own measures.

Chris Giles (The Financial Times editor) uses statistical arguments to conclude that the measures produced by the Bank of England are “nonsense” because (among other things) they suggest that “the labour market was probably worse in 2011 than at any time since before the earliest dinosaurs”.

I am not going to get involved into a debate about dinosaurs. Rather, I will try to address the question of whether the BoE’s measures are of (any) use in explaining UK inflation. If the answer is a definite “No”, then it makes sense for the Bank to drop reference to these measures. To address this issue, I estimate (using regression techniques) four standard models of UK inflation. Each one of these models attempts to explain inflation based on an intercept term, lagged inflation (as a measure of inflation persistence) and economic slack by reference to the three BoE slack measures as well as OBR’s output gap.

My findings are as follows:

- Both OBR’s output gap measure and the BoE’s unemployment gap measure have similar (in-sample) predictive power for UK inflation (in terms of standard diagnostics like the adjusted R-squared). Equally important, both measures resist the “passage of time” (in statistics this is equivalent to saying that these models “pass” parameter stability tests).

- On the other hand, the BoE’s measures of labour participation gap and average hours gap have lower (in-sample) predictive power for UK inflation. More worryingly, their use is extremely sensitive to the “passage of time” (as these models fail parameter stability tests).

- Nevertheless, one might argue that pooling information from the Bank of England’s three different measures is of some use in predicting inflation. To address this issue, I use a weighted average (with equal weights) of the three BoE measures. In this case, I fail to find any evidence that pooling information of the three labour slack measures is any better in explaining UK inflation than the three measures separately.

The implication of all of the above is that the BoE should probably drop reference to the labour participation and average hours gap measures of labour slack. As is often the case, less information (in terms of monitoring slack indicators) is more. Indeed, this appears to be the case with the Bank of England’s Inflation Report.