Recidivism rates amongst Victorian young offenders were significantly lower than today, revealing the value of providing “skills and stability”, say University of Liverpool researchers.

The After Care project, conducted by Department of Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology’s Professor Barry Godfrey and Dr Zoe Alker, studied the lives of 500 children passing through a range of industrial and reformatory schools in nineteenth-century England.

Digitisation

Recent digitisation of court records, census returns and birth, marriage and death indexes has made it possible to collate life histories of nineteenth-century young criminals and unlock Victorian England’s ‘artful dodgers’ for the first time.

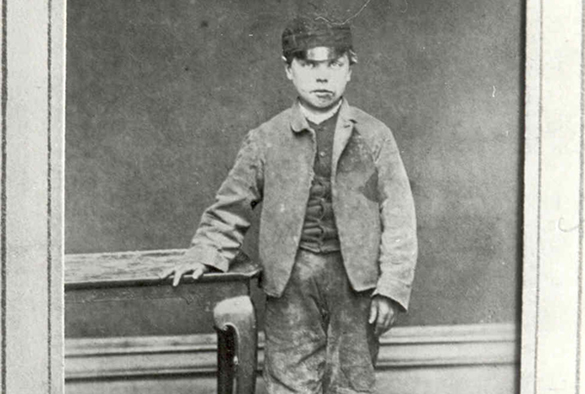

The majority of the young people studied were boys from poor and difficult backgrounds who were picked up by the courts for petty offences such as larceny, vagrancy or public disorder. Put in to industrial and reformatory schools until their late teens, many were placed in apprenticeship-type schemes for three years after their release.

This gave the boys essential skills to take in to the Victorian workplace and included trades such as hatting, shoemaking, farm work or the military.

The study found that only 22% of the 500 young criminal lives that were studied continued to offend after release. This is in stark contrast to recently released government figures that showed a 73% recidivism rate amongst today’s young offenders.

Dr Zoe Alker said: “We are unable to fully measure the impact of Victorian youth justice, however our findings suggest that residential stability and gainful employment helped young offenders in the nineteenth century ‘get back on track’.

“What’s shocking is that today’s young offenders aren’t given the same opportunities as their Victorian counterparts. Today, only 27% of men and 8% of women are released on to a job or training scheme which must count significantly towards the high reoffending rates of 73%.”

Skills and stability

“Youth Justice has always been subject to lurches in policy, but our study shows how important it is to provide skills and stability for young people living difficult lives before and after release.”

Professor Godfrey and Dr Alker worked alongside University of Essex’s Professor Pamela Cox and Dr Heather Shore of Leeds Beckett University, on the project.