Researchers at the University of Liverpool, together with UK and international partners, have launched a new global initiative to advance the development of a vaccine for river blindness.

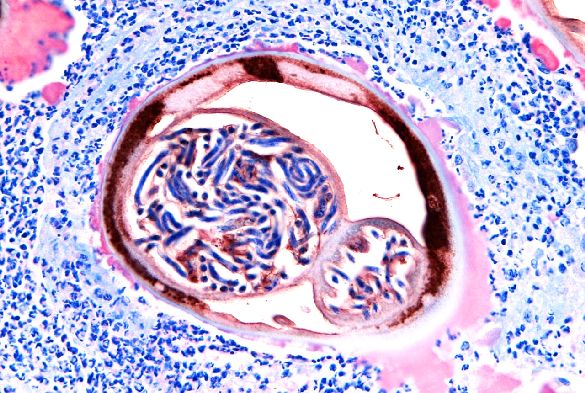

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by a nematode worm and transmitted through the bite of blackflies. An estimated 17 million people are infected with more than 99% of these cases spread through 31 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Infections can lead to blindness, but over 70% of infected individuals will suffer from an eruptive skin disease which can be severe and debilitating, with a particularly serious negative impact on the lives of women.

Over 30 years of research

The new partnership, called The Onchocerciasis Vaccine for Africa Initiative (TOVA), involves 14 international organisations, including the University of Edinburgh, the University of Glasgow, Imperial College London and the Sabin Vaccine Institute Product Development Partnership.

The Initiative builds on over 30 years of research by partner laboratories in Africa, Europe and the United States. This involved the development of preclinical models, as well as detailed immunological investigations of human infections, which ultimately led to the identification of several protective antigens as lead vaccine candidates.

Dr Benjamin Makepeace, from the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Infection and Global Health, said: “As part of this important global initiative, we plan to take one vaccine candidate to a phase one safety trial by 2017 and phase two efficacy trials by 2020.

“Following successful trials, this would be the world’s first vaccine for this long-neglected disease and will help us eradicate the parasite from the African continent.”

Future plans

The longer-term plan is to administer an onchocerciasis vaccine to children as part of national immunisation programme.

Vaccination aims to complement the current use of a drug called ivermectin, particularly in regions where mass drug administration cannot be implemented for safety reasons, and could make a major contribution to eliminating one of the most serious public health risks for African communities.

More information on TOVA can be found in an editorial by Dr Benjamin Makepeace and colleagues and on the TOVA website.