“Is a cyborg still a human? Are we already cyborgs? Should we be frightened of AI? Are we still human if our minds are uploaded into machines?”

Dr Will Slocombe, from the University of Liverpool’s Department of English, will present at the Being Human Festival this week, exploring representations of cyborgs, digital consciousness and virtual environments, as well as questioning how technology is changing us, our attitudes towards artificial intelligence, and considering what our relationship with machines might say about ‘being human’.

Here he talks to Claudia Wentworth, School of the Arts student, about the potential future of technology and considers the impact of its increasing presence in our everyday lives.

What made you want to delve so deeply into ideas of ‘being posthuman’ and the relationship between technology and humans?

“I’ve always been fascinated in how people ‘think’ – I nearly studied cognitive science rather than literature at university – and how we represent that, and I’ve always had an interest in science fiction.

‘Being posthuman’ is a way for me to share these interests, and to learn what other people think about the kind of issues involved. We tend to take technology for granted, making it invisible, and when it is seen, it is often perceived as evil somehow. I think the truth is somewhere in between, and that what we really need to do as a society is to work out what we think about it, rather than just accepting it.”

Would you consider yourself for or against the increasing impact of technology?

“I tend to be really interested in technology as a concept, but I’m actually something of a Luddite. Technology is not inherently evil, or the wrong direction for us to take, but I think we have to consider how we use it, rather than buying into the latest gadget or using it because it is there to be used.

“Technologies can often be used in surprising ways, and I would be cautious of criticising innovation for innovation’s sake, but we have to also take time to reflect on how it is changing us, individually and as a society. I suspect they might close as many doors as they open.”

Is the purpose of the event in any way a warning to trigger a response, and change our way of looking at technology?

“I don’t know about a warning, but certainly I want to prompt a moment of reflection, a ‘taking stock’ of where we are and where we’re going in technological terms. Of course, I also want to show people that science fiction, as much as it can be completely implausible sometimes, is also a kind of fictional test-tube for technology, speculating on what things might exist as well as how they might change us.

If you think about it, science fiction writers have given scientists a lot of ideas about what they might develop, and certainly coined terms (like ‘cyberspace’) before the technology existed in a meaningful sense. So one of my interests is in what I call “fictions of technology”, by which I mean not only the kind of stories that have technology at their centre, like science fiction, but also the fictions that we tell ourselves about technology and the kinds of stories that we build up around it: we have this myth of progress, for instance, that technological development is always moving us forward, making us better, but I don’t think that is necessarily true. For every medical application of a technology there’s probably a military one too – does that technology make us ‘better’ then?”

Where do you see our reliance on technology in 10 years time?

“I think we’re becoming more and more networked as a species, and as much as this can really be a positive thing in terms of fostering better understanding and lines of communication, I’m concerned that much of this is derived from market economics rather than need or use. We already have ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’; I think this gap is going to get much wider over the coming decade. It’s not so much about opting into or out of using technologies so much as whether you might even have the option of opting in or out, that really worries me.”

Your event explores the impact of technology on our everyday lives and how it might affect us in the future. Do you ever think humans will evolve in a way to have lesser brain capacity with increasing reliance on technology to perform tasks for us?

“I think evolution would take too long to catch up with technological usage for technology to have such an impact in physical terms. That said, technological interventions that change us physically and mentally are an almost certain thing, and I am equally sure that a reliance on technology can have an impact on our attitudes and our development.

We’ve always used writing as a kind of ‘external memory’ and with the advent of computers and smart phones, I think we’re doing that more and more, possibly to the detriment of our actual memory, which is a kind of developed skill. If we fix that by implanting computers in our heads, as some science fiction writers have suggested, we’re compounding the problem rather than solving it.

The same applies to knowledge; I don’t think we value knowledge as much as we used to, as it is seen to be easily accessible over the internet, but I think this prompts a kind of laziness of thought. We tend to rely on internet search engines to make the connections for us, rather than seek to work them through ourselves, and I think being able to find information is not the same as understanding the contexts around that information: that’s where real knowledge comes in.”

What do you think contemporary culture’s fascination is with artificial intelligence? Do you think it is in any way fuelled by mankind’s want to be lazy?

“I think most people would like to have robots to help with housework, for example, but I think they’d be too suspicious of the technology for it to really take off, at least in the near future, aside from the very specialised robots we already have.

For whatever reason, and however inaccurate it might be to do so, we tend to trust human judgement over that of a machine. We do tend to put quite a lot of value on humanity, distancing ourselves from other animals too, and so I think one of the interesting issues here is machine rights, because if a computer has to be as ‘intelligent’ as a dog or monkey to do a particular task, then doesn’t it deserve to be treated in the same way?

I think artificial intelligence takes quite a lot of thinking through, because it opens up a whole series of problems about definitions of what is ‘human intelligence’ and why that makes us so special. I think that’s the real reason why we’re fascinated by AI – we want to know what we look like to something as intelligent as us.”

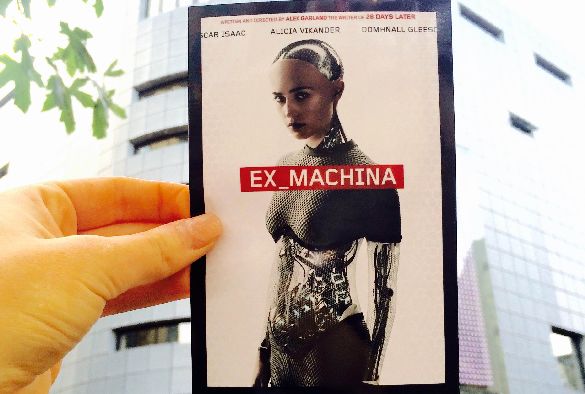

Do you think cinema’s obsession with artificial intelligence is setting a precedent to where technology is heading in the future? Do you think our consumption of these programmes and films make this future something we now expect and accept?

“I think people tend to believe a lot of what they see, and certainly these films, games, books, and tv shows tends to normalise that kind of view of the future (like flying cars or one-piece clothing in mid-c20th science fiction, although at least one of those didn’t come about). The current obsession with AI seems to be creating an environment in which people believe computers might one day take over the world if we’re not careful, and I think that attitude is worth exploring.

We worry about making machines smarter than we are, but so much of it depends upon what you call ‘intelligence’ and what it’s good for, and I think these kind of things are really worth thinking about critically. It’s far more interesting in some ways to work out why we’re thinking these things and representing the future in this way, rather than assuming that it reveals a self-fulfilling prophecy about the future: why are we so worried about machines at the same time as we rely on them so unquestioningly? What does that tell us about us?”

‘Being posthuman’ takes place on Saturday 21st November, 10.00-17.30 at FACT, Liverpool, as part of the University of Liverpool’s ‘Fantastic monsters and machines’ series of events for the Being Human festival.

To reserve free tickets, please visit: http://beinghumanfestival.org/event/being-posthuman/