By Professor Costas Milas and Dr Mike Ellington from the University’s Management School:

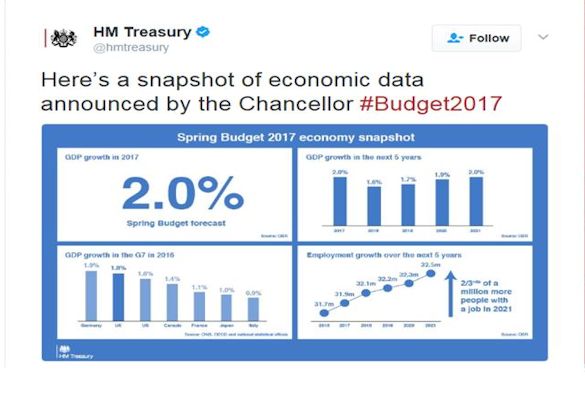

Philip Hammond has delivered his first budget since taking over the role of chancellor of the exchequer after the UK’s Brexit vote put paid to his predecessor, George Osborne. He has unveiled a brighter outlook for economic growth, with an upgraded forecast for growth in 2017 from the Office for Budget Responsibility. He spoke of job creation and wage growth. And, with public finances in better shape than expected, he was also able to report lower borrowing forecasts than in his Autumn Statement.

But recent history shows us why we should not be so confident about all these healthy forecasts. A look at the recent history of economic forecasting makes the upgraded expectations of 2% growth in 2017 questionable. Then there’s the fact that Brexit hasn’t happened yet. With Article 50 soon to be triggered, the uncertainty that harms economies the most will only get worse in the months to come.

The problem with forecasts

Deriving forecasts about the state of the UK economy and public finances is a huge challenge – in general – but especially now that we do not know how the UK’s relationship with Europe will shape up following Brexit. Indeed, the ancient Greek scientist Thales of Miletus was one of the first experts to (implicitly) recognise the challenges of forecasting by noting that “the past is certain, the future obscure”.

Reflecting the state of economic forecasting, the Bank of England’s interest rate setter Jan Vlieghe recently informed MPs: “We are probably not going to forecast the next financial crisis, nor the next recession. Models are just not that good.”

As astonishing as this statement might sound, Vlieghe knows exactly what he is talking about. Figure 1 shows the inability of policymakers (the Bank of England’s in this case) to forecast GDP growth two years into the future.

As the graph shows, policymakers’ ability to predict UK GDP growth has been rather poor. This can be seen in the way the forecast moves in the opposite direction to the actual outcome.

Figure 1 makes two further worrying readings. First, UK policymakers have been overconfident in their predictions. The Bank of England has, on average, over-predicted annual GDP growth by a massive 1.52% over the past nine years. Second – and perhaps much more worryingly – the Bank’s officials (and many other economists) completely missed the 2008-09 recession.

So what this tells us is that models are not good – at all – when they are needed the most. If this is indeed the case, what is the purpose of going through the somewhat futile exercise of presenting budget forecasts three to five (or even more) years into the future? Was this train of thought going through Phillip Hammond’s mind when he announced that there will only be one, rather than two major budget statements a year?

Revising the estimates

Irrespective of what Hammond’s thinking might have been, the health of the UK public finances critically depends on the country’s economic performance. This is hard to pin down. Indeed, provisional (or real-time) published GDP data are often revised quite dramatically down the line. This is more the case in periods of increasing uncertainty – such as the recent financial crisis and (arguably) the present volatile economic climate following the recent Brexit vote.

Figure 2 plots together provisional and revised estimates of annual GDP growth in the UK. The revised estimates reflect the latest belief of how the economy has performed based on the most recent information.

Although the correlation between provisional and revised GDP growth is quite high, a closer look at the data reveals the following:

1) During the 2008-2009 financial crisis, GDP fell earlier and more sharply than policymakers thought at the time.

2) Since 2015, provisional GDP growth data seems to be sending the rather misleading signal that the economy is doing better than it actually is.

This all has important implications for the UK’s public finances. Policymakers use data available in real time to produce forecasts about GDP growth and public finances. These forecasts should always be taken with a pinch of salt because real-time data (which are subject to potentially large revisions) are used as inputs in any forecasting model. To make things worse, forecasts critically depend on the underlying forecasting model, which is unlikely to adequately capture all the time-varying, evolving features of what we want to forecast.

The challenge of uncertainty

Even if we were to naively assume that provisional data remain unrevised and that we have an accurate forecasting model, economic uncertainty itself will challenge the economy. As Figure 3 shows, economic uncertainty takes its toll on annual investment growth, which in turn limits economic growth.

To keep buying UK debt, international investors will require a higher yield on UK bonds. This yield will also experience further ups and some downs as the UK goes through a potentially messy Brexit divorce. With economic uncertainty on the rise, UK investment will slow down. This will bring with it job losses and a reduction in public finances because of lower tax receipts and rising unemployment benefits.

The chancellor will no doubt be hoping that his plans to lower the UK’s corporate tax rate to 19% in 2017 and 17% in 2020 will keep businesses happy. But the UK’s existing corporate tax rate of 20% was already much lower than the 24% average for 34 OECD countries. It might be helpful for existing businesses and may even attract additional ones. But it will not be enough to counteract Brexit uncertainty. Business would definitely prefer assurances about a smooth divorce today rather than lower taxes in the future.

This article first appeared in ¬The Conversation’.