Claire Taylor is the Gilmour Chair of Spanish and Professor in Hispanic Studies in the University of Liverpool’s Department of Modern Languages and Cultures

In recent years we have seen a rise of what has been termed “artivism”: the bringing together of art and activism. Artivists see art as a social practice. They address particular societal concerns or inequalities and involve communities and activists, as well as other artists. For many of these artivists, new media technologies have provided particularly fruitful ways to engage in this. Different groups and collectives are variously promoting “tactical media”, “electronic civil disobedience”, and “hactivism” as ways of employing digital technologies in order to make creative, artistic protests.

Some particularly interesting examples of these types of conjunctions of art, activism, and new media, have focused on the US-Mexico border region, a space which has come under increased scrutiny in recent months, particularly in the light of Trump’s infamous plans to build a wall between Mexico and the US.

As part of my ongoing research on digital art and activism in Latin America, I’ve looked at artists whose work has focused on the US-Mexico border. Some of the features that they highlight in their work make clear that the situation is a lot more complex than the “them/us” rhetoric that Trump uses – a rhetoric that it is extremely important to overcome. These artists make work that attempts to express a non-nation state identity and provide a critique of the late capitalist conditions of the border economy.

Activist art

There have been many festivals and interventions on the border, including the Borderhack festivals that began in 2000, which aim to protest “the inequalities and dangerous conditions” that Mexican immigrants face. There is also the Tijuana Calling online exhibition, which makes use of new media technologies to explore the concerns of the border, and to investigate the ways in which technologies – often put to use to police these very borders – may be re-encoded in a resistant fashion.

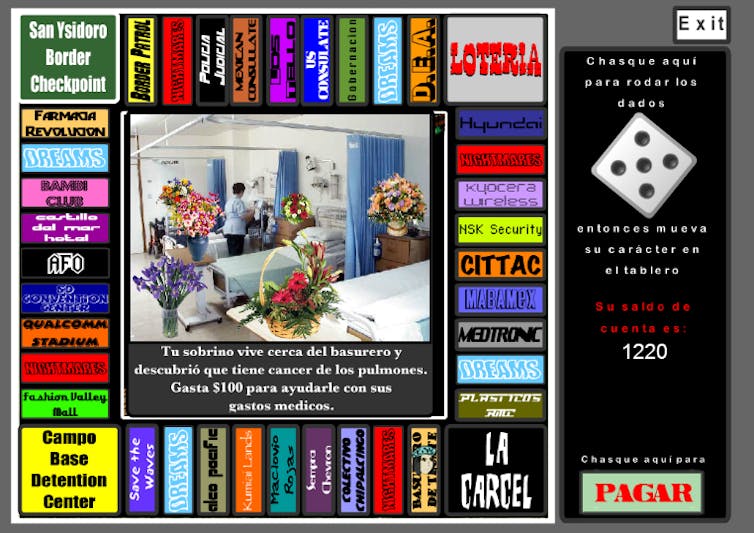

One such work is “Turista Fronterizo”, made in collaboration between Cuban-American performance and multimedia artist Coco Fusco and media hactivist Ricardo Domínguez. Turista Fronterizo takes the format of an electronic board game, loosely similar to the Monopoly format, but with the properties spaced along the San Diego-Tijuana border.

Image reproduced courtesy of Coco Fusco.

When we play the game – which can be done online – by moving our avatar to a new square, a short animation appears in the centre of the board commenting on the socio-political realities associated with each particular location. These avatars frequently make reference to real-life controversies, disputes and human rights abuses that have taken place within the border region. This is a work that encourages us to critique the structural inequalities of the border economy, and to take an active, critical position.

Another example is the work of Latino artist Ricardo Miranda Zúñiga. His recent project, A Geography of Being (2012), is an interactive installation consisting of a video game along with sculptures that contain electronic circuits that react to the game. Far from drawing the user into a purely ludic, pleasurable world, this game encourages them to reflect on social issues. It narrates the experiences of undocumented young immigrants in the US – young people who enter the US in search of better life opportunities. The game positions the player in the role of an undocumented youth who needs to negotiate the virtual world and learn about the hardships that such young people face.

Image reproduced courtesy of Ricardo Miranda Zúñiga

Perhaps one of the most high-profile examples of the creative use of digital technologies to contest dominant neoliberal logic and enable cross-border identities is the Transborder Immigrant Tool (2010). This is a mobile phone app that uses GPS to aid undocumented migrants to find sources of water when crossing the US-Mexico border, as well as showing the location of the nearest US Border Patrol stations and other landmarks on both sides of the border. Installed onto recycled mobile phones, and distributed free to migrants, the tool has been dubbed a “virtual divining rod”. As well as providing practical support, the tool raises important issues about inequalities and access in the border region.

These artists often present the US-Mexico border as a continuous space. They emphasise that the US-Mexico border has a complex – if fraught – shared history, that doesn’t fit neatly into national borders.

Protest politics

Perhaps the most important role of these artists and activists is the way they often protest against the sorts of neoliberal policies imposed on the border region by the US.

It’s widely accepted that NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement has ensured the US access to an abundant supply of cheap labour south of the border. NAFTA has long been the subject of criticism by Mexican activists for its devastation of the traditional Mexican rural economy.

Indeed, the reality of the border is that the US economy relies on a disavowed underclass of cheap Mexican labour. This labour comes from the same US policies, enacted through NAFTA, which drove Mexican peasants from their land, and created a disposed class who were forced to look for work in the maquiladoras – factories run by a foreign company exporting its products – so common on the border. The rhetoric of President Donald Trump, in which Mexicans (them) are coming to steal our jobs (us) is therefore much more complex than it appears.

In these ways, artists – both those living in the border regions and elsewhere – have been engaging creatively with border experiences for years. Their works provide a nuanced and complex take on what it is like to live in the border region, and encourage viewers to take a critical stance as regards the inequalities faced by many living there.

Perhaps the greatest indicator of the importance of their work is the reactions that they have generated. In 2010 for instance, three Republican congressmen called for an investigation of the Transborder Immigrant Tool, and Ricardo Domínguez was threatened with loss of tenure from University of California San Diego. Fortunately, Dóminguez remained in post, and his work, and that of other artivists, continues.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.