Dr Clare Downham is a Viking expert and Senior Lecturer in the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Irish Studies.

The words Zombie and Vampire both entered the English language relatively recently (in the early nineteenth century), but belief in revenants – that is in reanimated corpses – has been found in many different cultures at different times, stretching back thousands of years.

Medieval Icelandic sagas give detailed insight into beliefs in revenants. The reanimated corpses described in these texts tend to be hideous malevolent creatures, and much nearer the contemporary concept of zombies rather than the suave and sometimes sexy images we see of modern vampires. There is only space here to describe two examples from the rich story-lore surrounding revenants.

Olaf and the restless corpse

Laxdaela Saga is one of the most famous Icelandic sagas of the thirteenth century, and the plot is a bit like a complicated soap opera with supernatural elements thrown in. It includes the tale of a strong and stubborn man called Hrapp. When he is about to die he demands that his wife buries him upright under the doorway of his hall, but the corpse is restless and after a series of deaths his hall is abandoned. Sometime later, a man called Olaf buys Hrapp’s property at a cheap price, but he soon encounters the dead man one dusk when gathering his cattle. The next section is quoted from the saga:

Olaf went to the gate and struck at him with his spear. Hrapp took the socket of the spear in both hands and wrenched it aside, so that the spear shaft broke. Olaf was about to run at Hrapp but he disappeared …The next morning Olaf went to where Hrapp was buried and had him dug up. Hrapp was found undecayed, and there Olaf also found his spear-head. After that he had a pyre made and had Hrapp burnt on it, and his ashes were flung out to sea. After that no one had any more trouble with Hrapp.

Grettir and the mound-dweller

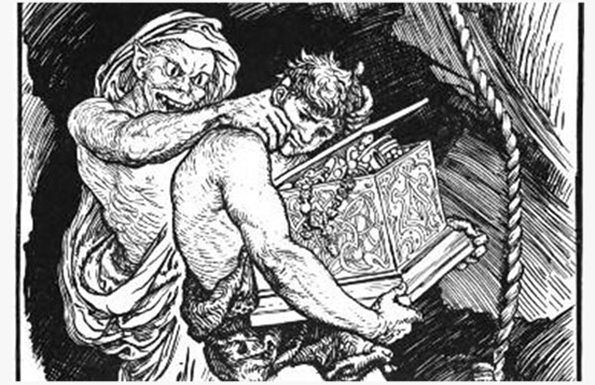

The fourteenth century Grettir’s Saga is the story of a troubled youth and outlaw, who encounters two of the undead in his lifetime. On the first occasion, he breaks into a pagan burial mound in a desire for adventure and approval:

Then he descended into the mound. It was very dark … Grettir took all the treasure… but on his way, he felt a strong hand pull him back… The mound-dweller made a ferocious onslaught… and here they struggled for long, each in turn being brought to his knees. At last it ended in the mound dweller falling backwards with a horrible crash, … Grettir then drew his sword Jokulsnaut, cut off the head of the mound dweller… Then he went with the treasure.

In this story, the way to defeat the revenant is different to the account in Laxdaela saga (beheading rather than cremation), but the revenants are similar in their strength and belligerence. Later on, Grettir finds himself volunteering to take on another zombie. This was a shepherd Glámr who had died under mysterious circumstances and who is rising from his burial mound to terrify his former neighbours. When Grettir hears the story, he goes to stay in the hall which is haunted by Glámr. The revenant does not disappoint, entering the building at night in the guise of a giant. A desperate fight breaks out between them:

The benches flew about and everything was shattered … Glámr … tearing away the lintel with his shoulder and shattering the roof, the rafters and the frozen thatch. Head over heels he fell out of the house and Grettir fell on top of him. The moon was shining very brightly outside…. Grettir … when he saw the horrible rolling of Glámr’s eyes his heart sank so utterly that he had not strength to draw his sword, but lay there between life and death.

Although the evil eye of Glámr briefly renders Grettir powerless, he rallies. Glámr curses Grettir before he is beheaded. Afterwards, Grettir has the body cremated and buried a long way ‘from the haunts of men or beasts’. This seems a watertight way to defeat a zombie by both beheading and cremation. There is a high price to pay for the victory however, as the rest of Grettir’s life is blighted by Glámr’s curse.

Supernatural beings – what do they represent?

It has been suggested by some writers that these supernatural beings in Icelandic literature might be metaphors for plague, mental illness or other trauma in a person’s life. The modern terms and concepts to discuss trauma were lacking in medieval Icelandic society and talking of zombie-like creatures provided in indirect route to touch on such issues. Similarly, nowadays, we might sometimes refer to mental illness as a black dog or inner demons, representing a problem as another entity, in order to discuss it.

The undead have also be repurposed through the centuries to serve as powerful metaphors for social concerns. For example, in contemporary society, the vampire who doesn’t seem to belong in society, may represent the struggles of alienated teenagers, while the representation of herds of mindless of zombies driven by greed can sometimes serve as a symbol for humanity’s wilful destruction of the planet we live in. The reduction of these dark images to kitsch humour at times is also a way of laughing in the face of fear. It is the adaptability of the undead in mirroring the concerns of society that have made them a source of fascination for centuries.