Professor Thomas B Fischer and Dr Olivier Sykes from the University’s Department of Geography and Planning consider the issue of Impact Assessments in light of events this week:

Impact Assessments (IAs) have certainly received a lot of media attention recently.

This week, David Davis, the UK government’s Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, admitted to a Select Committee that the 50 to 60 IAs that he had claimed his Department had been preparing on the implications of the UK leaving the EU had not been carried out.

One of Davis’ key statements on the matter of IAs was that he was ‘not a fan of economic models because they have all proven wrong’.

Yet the notion that IAs are mere ‘economic models’ is rather startling from an IA expert’s point of view.

It is true that Cost-benefit analyses (CBAs) are economic models that are routinely used in justifying investment decisions. They function using mathematical equations, comparing estimated costs to implement a policy / a development on the one hand, and likely economic – monetary – benefits on the other.

Results of CBAs do indeed often turn out to be wrong, partly due to consistent cost overruns of projects and partly due to meddling of decision makers with the parameters used within them.

Yet whilst variants of CBAs have been in use since the mid-19th century, the term ‘impact assessment’ (IA) is more recent and denotes something quite different. It was initially associated with Environmental impact Assessments (EIAs) in the 1970s. Subsequently, it became applied for a multitude of other purposes, including health, social and the wider sustainability agenda.

The kinds of IAs at the heart of the ongoing controversy around the UK leaving the EU are routinely prepared in the context of drafting government policies and were until recently called regulatory IAs. There is a government template which provides a list outlining the purpose and focus of an IA, which it states should include:

- a “description of the problem under consideration’,

- [the] rationale for [the] intervention;

- [the overall] policy objective,

- [a] description of options considered (including status-quo),

- monetised and non-monetised costs and benefits of each option (including administrative burden);

- [the] rationale and evidence that justify the level of analysis used in the IA (proportionality approach);

- risks and assumptions;

- direct costs and benefits to business calculations

- [… and what is referred to as] wider impacts”.

With regards to wider impacts, reference is made to an IA Toolkit, which was released by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) in 2011. This document reveals that the approach used is broadly in line with an internationally accepted understanding of what IAs should look like.

They are participatory, transparent and open decision support procedures, consisting of various (logical) steps. The assessment of different options is at the heart of assessment, focusing on various economic and other impact areas.

This suggests that David Davis’ understanding of IAs as ‘economic models’ is fundamentally flawed when set alongside accepted definitions used by UK government.

In order to be able to make informed and transparent decisions about future policy choices, comprehensive and participatory IAs, considering, not just sectoral, but wider-economic, societal and environmental impacts of different options should be prepared, going far beyond what economic models aim to achieve. What is particularly advisable in the light of the significance of the changes that leaving the EU will unleash, is the consideration of the potentially differential regional effects -as for some regions economic and other consequences are likely to be more severe than for others.

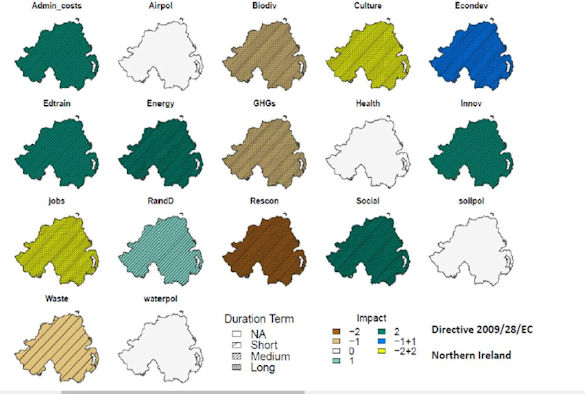

In this context, the Environmental Assessment and Management Research Centre of the University’s School of Environmental Sciences has contributed to the development of an approach which has been termed ‘territorial impact assessment’.

It was originally developed in order to help understand potential impacts EU policies (directives and others) may have on different European regions. Its rationale is connected with a desire to allow every region within Europe to develop its full potential within a long term sustainable development.

Given that TIA considers social, economic and administrative aspects it is therefore a highly suitable tool to consider the differential economic, social, environmental, UK-wide and regional impacts of leaving the EU. In this way it might help decision makers and citizens anticipate the impacts and consequences and plan to mitigate these and try to develop their resilience in the face of an uncertain future.