Professor Peter Shirlow is Director of the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Irish Studies.

It would be downright bizarre to claim that the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) solved all of Northern Ireland’s problems – although it did shift the gun out of Irish politics. The very existence of Northern Ireland remains the defining fault line between unionists, who wish to remain in the UK, and republicans, who want to unite Ireland.

For republicans, the GFA was a holding operation. And given demographic changes, they feel that Irish unification is now within sight. With the republican community of Northern Ireland growing faster than the unionist, they believe the majority of the population will soon share their perspective. For unionists there is the inherent fear of being outnumbered – although many more Catholics (around one in five) favour remaining in the UK than do Protestants wishing for Irish unification (around one in ten).

But the GFA did create new social spaces. Today, a younger generation in Northern Ireland is slowly escaping the confines of ideological, social and cultural enclosure. Around one in five long-term relationships in Northern Ireland are now across the sectarian divide. Such relationships were once near heresy.

The vast majority of those who grew up over the past two decades have friendships across the divide that were unimaginable to their parents. Northern Ireland election surveys conducted at the University of Liverpool show that nearly half of those aged 18-24 do not choose the labels unionist or republican when asked about their identity.

A people’s movement

Unfortunately, the perpetual fascination with the Northern Ireland Assembly’s various machinations drowns out this progress. And the anniversary of the agreement is a similar story.

Marking 20 years of the GFA will mean being reminded of senator George Mitchell’s ability to drag politicians over the line and of prime minister Tony Blair’s summation that reaching an agreement meant that “the hand of history is upon us”. Although it’s right to celebrate such leadership and to discuss the failures of the GFA to sustain devolution, a more precise account should point to how people sustained the GFA and the desire for peaceful coexistence.

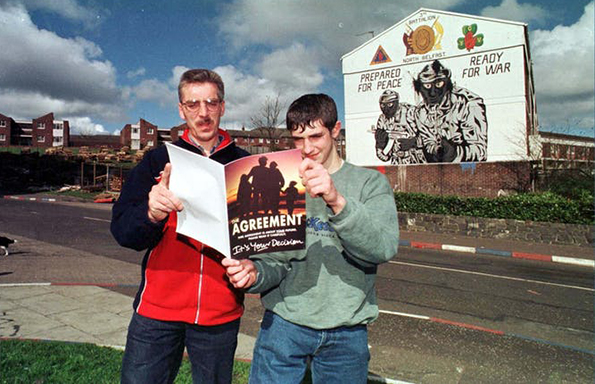

The GFA does not and never did belong to the politicians. Its owners are the people who voted for it across the constitutional divide and sent out a resounding message that they were wearied by a conflict that did not correspond with their desire for a society based on parity of esteem. On May 22 1998, they voted overwhelmingly in support of the deal in referendums held both north and south of the border. For every person who voted against, 18 voted for. The people sent a clear message that they were repulsed by violence and supported democratic means alone. They were merely waiting for the politicians to catch up with them. The GFA, and the overwhelming endorsement of it, was a silent revolution.

A critical aspect of the GFA was the significant de-escalation in violence. Between 1968 and 1998, some 3,600 were killed and 30,000 injured or imprisoned. In that period, there was an average of 110 killings per year. Last year, there were just two.

This agreement led to the Irish Republican Army (IRA) accepting the unthinkable in terms of its ideology. It recognised and approved the principle of consent. That principle enshrines the right for constitutional change based upon majority support. The people believed in consent and thus rejected the use of armed violence to achieve political goals. Their endorsement was the death knell of violence.

The increasing agnosticism about identity in Northern Ireland is evocative of the GFA’s desire to create a new sense of identity. The people now support inter-community marriage and wish for equal treatment for sexual minorities and women. It’s they who step across the sectarian divide while politicians fail to do so.

It is the people who have known loss, suffering and harm, who are most sensitive to compassion and a way forward. Former conflict-related prisoners worked to re-image murals to remove the allure of violence. Victims worked with those who caused harm to share ideas on how to sustain peace. Police and community members once hostile to each other constantly reduce sectarian tensions to embed peace. Civic, religious and community leaders challenged sectarian prejudice while the Assembly constantly teetered on the edge, crashed and rose and crashed again.

The silent revolution of the people channelled the GFA – it was not the GFA that guided them.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.