Eve Rosenhaft is Professor of German Historical Studies in the University of Liverpool’s Department of Modern Languages and Cultures

The genocide of the Roma by the Nazis remains for many the “forgotten Holocaust”. February 26, 2018 marked the 75th anniversary of the day in 1943 when, following an order issued by SS leader Heinrich Himmler the preceding December, the first transport carrying German Sinti and Roma arrived at the “Gypsy Camp” in Auschwitz-Birkenau – the beginning of a wave of mass transports which peaked that March. By war’s end, some 20,000 Sinti and Roma had been murdered in Auschwitz or died as a consequence of their internment there.

The families of the victims of the Roma Holocaust still struggle for compensation and equal rights. Meanwhile, institutional and rhetorical anti-Gypsyism is sadly becoming politically respectable in parts of Europe.

Yet at the same time, the way the Romani Holocaust is commemorated and represented is shifting. Thanks above all to the mobilisation of Romani communities, physical memorials are proliferating, from the central memorial to the murdered Sinti and Roma in Berlin, which opened in 2012, to local initiatives all over Europe.

Holocaust testimony in many forms, such as photographs and survivor accounts, is intrinsic to new cultural initiatives such as RomArchive’s digital archive of Romani culture.

Museums are also responding. In the UK, the Holocaust Galleries at the Imperial War Museum in London are currently under review. As I learned in conversations with some of those involved, this is partly being done with a view to integrate the fate of the Roma into a more comprehensive narrative. In its 25th year, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC (USHMM) is also reassessing its permanent exhibition. There, too, I’ve learnt that one outcome will be the more effective deployment of its now substantial holdings on the Roma in educating its own staff and updating the displays.

Museum practices reflect the ways in which scholarship on the Romani Holocaust has broadened and deepened, often through partnerships between research and educational institutions. For example, the USHMM can draw on the work produced through its own Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, which has invested substantially in research and teaching on the subject.

Romani persecution

One thing that recent scholarship makes clear is that those who passed through the gates of Auschwitz were only a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of Romani victims of the genocidal policies of the Nazis and their allies. In occupied Poland, Serbia and the Soviet Union, they were hunted down by the same Wehrmacht units and death squads that massacred Jews. In Romania, some 25,000 were deported to “colonies” east of the Dniester river (Transnistria); nearly half of them did not survive the brutal conditions there.

Before the 1943 deportations from Germany, there had already been two large scale removals of Sinti and Roma: 2,500 shipped to primitive camps in Poland in 1940, and 5,000 deported to the Łódź ghetto, where those who did not die of typhus were sent to the gas chambers at Chelmno.

The victims of the Romani Holocaust also include many who suffered internment without ever leaving their home territories. The names of the Lety and Hodonin camps in what is now the Czech Republic and the Jasenovac camp in Croatia are notorious for the crimes committed against Roma interned there.

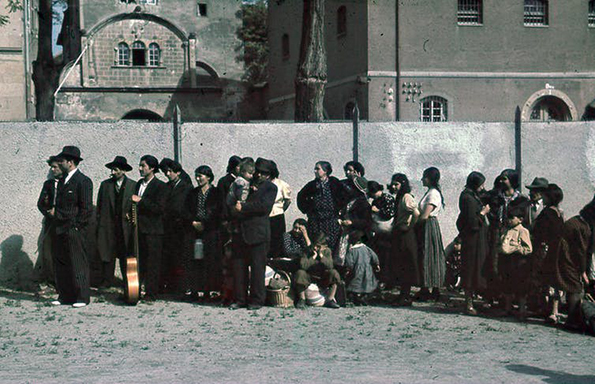

In Germany, internment of Roma began as early as 1935, in designated camps set up by local authorities. Under permanent police surveillance, forced to work for local firms, labelled as “antisocial” and increasingly criminalised, many were already in SS concentration camps by the late 1930s. They included several hundred “Gypsy” men targeted for arrest in mid-June 1938 during “Operation Workshy”, which also saw the first mass arrests of Jews and some 10,000 others. Most of these Romani prisoners never saw Auschwitz, but were shipped from one camp to another over the years, permanently available to the SS, while they were alive, for exploitation.

Life and death in Auschwitz

Auschwitz remains a powerful symbolic point of reference for European Roma – as it does, of course for global memory of the Holocaust. August 2 is commemorated annually in memory of the “liquidation” of the “Gypsy Camp” there in 1944, when 2,900 men, women and children were gassed in a single night. Increasingly, Roma communities also mark May 16, 1944, when, as survivors remember, the inmates successfully resisted the SS’s first attempt to clear the camp.

Auschwitz was a special kind of hell for Sinti and Roma. Himmler’s order decreed that they should be deported “as families”, and in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Section BIIe was set aside for them as a “family camp”. They were “allowed” to wear their own clothes and let their hair grow. Children were born. Non-Romani observers, including Jewish inmates and political prisoners, sometimes imagined that this made life easy.

But Romani survivors remembered that they had to watch as their children and parents, brothers and sisters were humiliated and abused, and as they died from malnourishment, exhaustion and disease. Arriving as relatively healthy, relatively young people, they also constituted a ready supply of “human material” for the experiments of SS physicians such as Joseph Mengele, whose “medical” facility was immediately adjacent to their camp.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.