The “adoption gap is going to continue” unless ethical issues around smart cities are addressed, Professor Rob Kitchin told a Heseltine Institute for Public Policy and Practice audience.

In a scathing assessment of the uptake of the smart city concept, Prof Rob Kitchin, one of the world’s leading human geographers, identified problems of privacy, consent, value, security, social division and technological maturity, among others, as key causes of the concept’s current failure to live up to the hype.

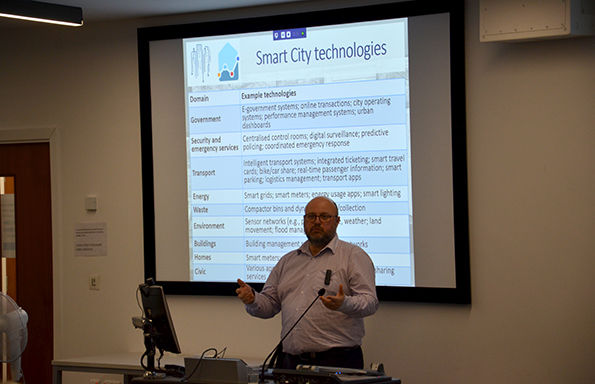

Prof Kitchin was speaking at the University of Liverpool’s Management School, as part of the Heseltine Institute’s public lecture series.

Describing the smart city as a “system of systems” and a “technocratic way of managing what goes on”, Prof Kitchin said the idea had existed for a long time but had always been presented as “a kind of civic paternalism” rather than something in which citizens are directly involved.

Prof Kitchin, Principal Investigator of the Programmable City project at National University of Ireland Maynooth, said: “Is the smart city primarily about creating new markets for profit? Or is it about improving quality of life for citizens?

“Very few cities work through these kinds of questions.”

He told the audience that cities are “really difficult to predict” and “really difficult to capture in code”, adding that the kind of technology smart cities utilise “does not address structural issues”.

Prof Kitchin said: “The way to deal with traffic is to get people out of their cars and onto public transport and bikes – it’s not about developing an app.”

He said that some cities are administered in convoluted ways, creating further difficulty, and that most “want to be second” in order to learn from others’ errors or best practice before committing to technological change.

But, crucially, Prof Kitchin raised the lack of “democratic oversight” and “citizen involvement” in the smart city agenda, as currently envisioned.

He said: “We’re data points. We’ve never been consulted and there is no notice of consent in these systems.”

He pointed to ‘anticipatory governance’, ‘predictive profiling’ and ‘dynamic pricing’ as examples of organisations using the kind of technology associated with smart cities, without citizen consent, asking; “who decides who gets nudged?”

To address these issues, Prof Kitchin said those pushing the smart city agenda must improve privacy and security and embrace end-to-end strong encryption, as well as developing a smart city advisory board and strategy, a risk and compliance board, core privacy/security team and a computer emergency response team.

Prof Kitchin added: “Not enough attention has been paid to these issues. Unless attention is paid, the adoption gap is going to continue and we won’t have the type of smart city we want to live in.”

To find out more about the activities of the Heseltine Institute for Public Policy and Practice, please visit www.liverpool.ac.uk/heseltine-institute/