A new study by the University of Liverpool, in collaboration with the Universities of Lancaster and Oslo, sheds light on a longstanding question that has puzzled earth scientists.

Using previously unavailable data, scientists at the University confirm a correlation between the movement of plate tectonics on the Earth’s surface, the flow of mantle above the Earth’s core and the rate of reversal of the Earth’s magnetic field which has long been hypothesised.

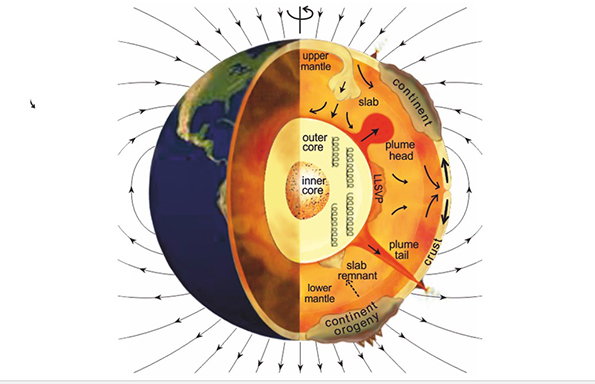

In a paper published in the journal Tectonophysics, they suggest that it takes around 120-130 million years for slabs of ancient ocean floor to sink (subduct) from the Earth’s surface to a sufficient depth in the mantle where they can cool the core, which in turn causes the liquid iron in the Earth’s outer core to flow more vigorously and produce more reversals of the Earth’s magnetic field.

This study is the first to demonstrate this correlation using records and proxies of global rates of subduction from various sources including a continuous global plate reconstruction modeldeveloped at the University of Sydney. These records were compared with a new compilation of magnetic field reversals whose occurrence is locked into volcanic and sedimentary rocks.

Liverpool palaeomagnetist, Professor Andy Biggin, said: “Until recently we did not have good enough records of how much global rates of subduction had changed over the last few hundreds of millions of years and so we had nothing to compare with the magnetic records.

“When we were able to compare them, we found that the two records of subduction and magnetic reversal rate do appear to be correlated after allowing for a time delay of 120-130 million years for the slabs of ocean floor to go from the surface to a sufficient depth in the mantle where they can cool the core.

“We do not know for sure that the correlation is causal but it does seem to fit with our understanding of how the crust, mantle and core should all be interacting and this value of 120-130 million could provide a really useful observational constraint on how quickly slabs of ancient sea floor can fall through the mantle and affect flow currents within it and in the underlying core.”

The magnetic field is generated deep within the Earth in a fluid outer core of iron and other elements that creates electric currents, which in turn produces magnetic fields.

The core is surrounded by a nearly 3,000 km thick mantle which although made of solid rock, flows very slowly (mm per year). The mantle produces convection currents which are strongly linked to movement of the tectonic plates but also affect the core by varying the amount of heat that is transferred across the core-mantle boundary.

The Earth’s magnetic field occasionally flips its polarity and the average length of time between such flips has changed dramatically through Earth’s history. For example, today such magnetic reversals occur on average four times per million years but one hundred million years ago, the field essentially stayed in the same polarity for nearly 40 million years.

Professor Biggin heads up the University’s Determining Earth Evolution from Palaeomagnetism (DEEP) research group which brings together research expertise across geophysics and geology to develop palaeomagnetism as a tool for understanding deep Earth processes occurring across timescales of millions to billions of years.

It is based in the University’s world class Geomagnetism Laboratory and supported through the Leverhulme Trust and the Natural Environment Research Council.

The paper `Subduction flux modulates the geomagnetic polarity reversal rate’ is published in Tectonphysics (doi: 10.1016/j.tecto.2018.05.018)