Originally published on The Conversation, this article was written by Lucy Williams, Postdoctoral Research Associate, and Barry Godfrey, Professor of Social Justice at the University of Liverpool.

In the centenary year of the 1918 Representation of the People Act, women’s struggle to obtain the right to vote in the UK has been strongly identified with its leading protagonists, the Pankhurst family. The rifts between Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia have become almost as famous as the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the organisation they founded in 1903.

Wikimedia Commons.

However, more often than not, Emmeline Pankhurst’s youngest daughter, Adela, is missing from the discussion. Adela was born in Manchester in 1885, the third Pankhurst daughter. She enjoyed a thoroughly genteel middle-class upbringing, like the rest of her siblings, and by the early 20th century, despite her mother’s objections, trained to be a teacher. In 1903, along with her mother and sisters, she helped to form the WSPU and the militant campaign for suffrage was born.

Like many campaigning women, Adela spent time in prison for the cause. She was one of several suffragettes arrested and imprisoned in Dundee in 1909. She was incarcerated for breaking the peace as she tried to disrupt a government meeting. Dundee Prison, controlled by the secretary for Scotland rather than the English Home Office minister, was one of the few to resist the new policy of force feeding hunger strikers.

Adela, unlike her mother and sister Christabel, spoke and wrote often against violent tactics and approved of a more co-operative relationship between the prisoners and prison staff. Later that same year, speaking on behalf of other suffragettes who had been released following a hunger-strike at the prison, Adela reported to the Edinburgh Evening Dispatch newspaper that the prison warders had “all showed great consideration and kindness”.

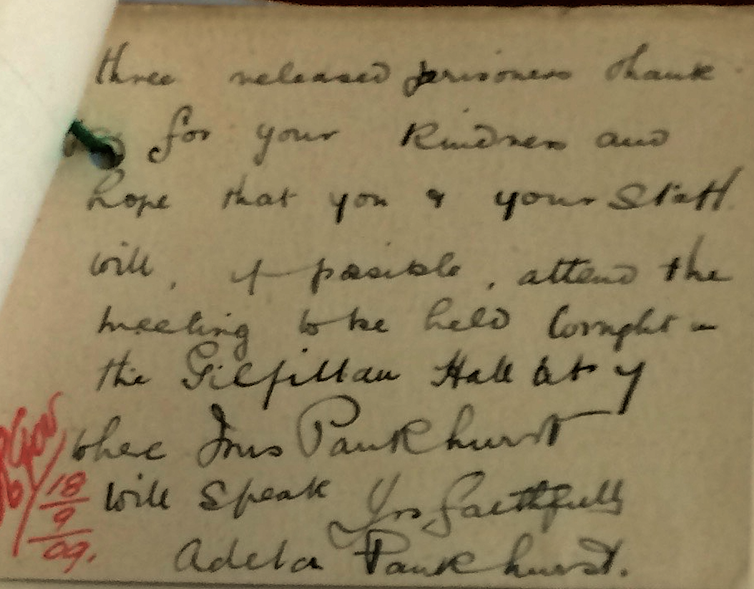

Barry Godfrey., CC BY-NC-ND

As testament to the good treatment she and the Scottish suffragettes had received at the hands of the authorities, she wrote personally to the governor of Dundee Prison inviting him and his staff to a nearby meeting where her mother was scheduled to speak.

As World War I approached, Adela and her sister Sylvia strongly disagreed with WSPU strategy which they considered unnecessarily violent. As punishment for breaking with the fold, in February of 1914, her mother gave Adela a one-way ticket to Australia (which already had female suffrage), where she remained politically active for the rest of her life.

Militants? Martyrs? Myths?

Her sisters and mother have become synonymous with the movement that won votes for women, and the Pankhurst family are rightly celebrated for their leading role in women’s suffrage, but Adela has all but disappeared from history.

Adela’s disappearance from collective memory cannot simply be explained by her “banishment” to Australia. After all, her sister Sylvia lived and campaigned against colonialism in Ethiopia and remains one of the most famous faces of the suffrage movement.

The key to Adela’s fall from grace lies perhaps not in her contribution to the campaign for votes for women in the UK, but in the more controversial causes she gravitated towards once the battle was won. She denounced contraception, abortion and even nursery schools for undermining maternal instincts and responsibilities. She campaigned heavily against Australian participation in World War I (the WSPU had suspended its activities, in order to support the war effort).

After dabbling in the newly emerged Australian Communist Party and subsequently rejecting the ideology, Adela’s politics shifted to the right, and she went on to be associated with the Australia First movement, an anti-communist, anti-immigration political party. In the 1930s, Australia First was an anti-semitic and proto-fascist organisation which favoured an alliance with Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Due to her activities with Australia First, Adela was interned in a camp for political prisoners in March 1942 where she remained for several months.

She died in Australia in 1961, having had, seemingly, a very happy family life there. Yet despite being named alongside 58 others on a statue of Millicent Fawcett recently unveiled in London, Adela Pankhurst has been largely ignored by popular histories of suffrage.

G. Ware., CC BY

Acknowledging the huge debt that society owes to the Pankhursts and the women who campaigned with them to deliver universal suffrage does not mean that historians and researchers should “iron out” uncomfortable truths. It isn’t always easy to reconcile the reality of the suffragettes as people with the way society wants to remember the movement.

Women like Adela Pankhurst are difficult to place, problematic to commemorate, and often easier to just remove from our collective history. However, the very reasons that she has been partly erased from history are exactly the reasons why she should be included. When we fail to acknowledge that campaigns for social change are often riddled with contradictions, flawed heroes, arguments over strategy, and many false turns before success, we risk producing sanitised versions of history. The full story of Adela and the other Pankhursts reminds us that messier but more complete histories of such struggles are worth recording and commemorating.

Lucy Williams, Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Liverpool and Barry Godfrey, Professor of Social Justice, University of Liverpool

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.