Dr David Jeffery is a Lecturer in British politics in the University of Liverpool’s Department of Politics

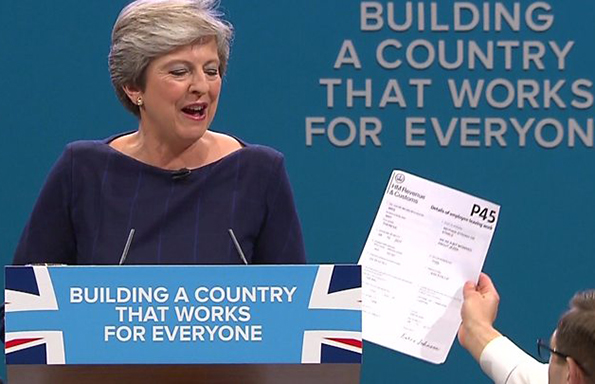

After last year’s Conservative Party Conference, where Prime Minister Theresa May faced her party after losing her majority in a shock electoral defeat just four months earlier, and where her speech was interrupted by a comedian handing her a P45 as her voice cracked and the stage collapsed around her, she might assume things could only get better.

She might be wrong.

Theresa May goes into her party conference in Birmingham in dire straits. Her Chequers Plan for Brexit – which would see the UK remain in the single market for goods but not services – was meant to square the circle of leaving the EU without erecting a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

However, Chequers was quickly trashed. EU officials rejected the proposals at a recent summit in Salzburg and members of the European Research Group (80ish pro-Brexit Tory MPs) threatened to vote against the plan if it was presented to parliament.

May quickly doubled down. She returned from Salzburg with a strong message for the EU – that the UK must be treated with respect during these negotiations – and was praised on the front pages of the British media for it. Then, she hit back at Chequers nay-sayers within her own party by stating that no deal was better than their ERG’s preferred alternative, a Canada-style deal called ‘Plan A+’.

So what does this mean for the Conservatives’ conference this weekend?

Firstly, each speech given on the main stage – and at the numerous fringe events outside the secure zone – will be painstakingly analysed for ministers’ and MPs’ positions. Adjectives, pauses, and even clothing choices will be deconstructed for clues: are they pro-Chequers? Do they prefer EFTA to Canada-plus? Or perhaps, like most of the public, are they more WTF than WTO?

Secondly, there will be positioning by the ‘next generation’ of Conservative MPs, laying their stall for when May steps down. Not much unites Conservative MPs nowadays, but one thing that does is the thought that May should not see the party into the next general election – and so the top spot will be up for grabs. The next election has to be held by 2022, and the party would want to give a leader time to bed in – a leadership election after Brexit makes intuitive sense. MPs are getting ready: expect speeches by Home Secretary Sajid Javid and Chief Secretary to the Treasury Liz Truss to be closely watched.

Finally, there will be plenty of people in Birmingham who will want to talk about ABB – Anything But Brexit. Despite appearances, the Conservatives are in government and there are many MPs who have new, radical and bold ideas for reshaping Britain which have nothing to do with our relationship with the European Union. The spate of new right-wing think tanks over the last year is testimony to this. Look for hints of the party’s post-Brexit/post-May domestic agenda at these fringe events.

In normal times, a leader like Theresa May would have been booted out by the Conservatives a long time ago – but these aren’t normal times. May will survive the party conference – regardless of how good or bad her speech is, regardless of what stunts Boris pulls, and regardless of how the conference is received by the public (those who care enough to follow it, anyway) – for the simple fact that there is no realistic alternative to May.

Jacob Rees-Mogg and Boris Johnson may be popular with the membership, but most of PCP would rather have a bucket of cold sick as their leader. Similarly, Brexiteers would never countenance someone like Chancellor Philip Hammond who has been lukewarm in his support for Brexit, and they would be unlikely to support an MP who didn’t vote leave in the referendum. Anyone else vying for the leadership probably sees Brexit as a poison chalice – why not wait until it is sorted by May and then start their own leadership unencumbered?

So for all the analysis that the conference will generate, my money is on little changing over those four days in Birmingham.

May returned from Salzburg with a strong message for the EU? Surely the idea was to go to Salzburg with a strong message? We are talking absolute basics of diplomacy here. It was Theresa May who on 29 March 2017, notified the European Council of the intention to leave the European Union under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. Just one month later on 29 April 2017, the European Council set out the EU’s overall positions and principles. Furthermore, considering it was a British White Paper from Arthur Cockfield in the 1980s that identified 300 measures to be addressed in order to complete a single market which led to the Single European Act, and then Single Market by 1992, no wonder there is surprise among our EU partners that the institutional memory of the current British state leads it to propose unworkable solutions to the current impasse. Note – 300 measures, so not something to be dealt with on the back of a cigarette packet by the weakly skilled politicians such as those we have sent to negotiate with the EU! Talk of “respect” is all very shrill in such circumstances – presenting half-developed proposals to the rest of the EU shows little respect given all the time and expense involved for all concerned. The Conservative Party needs a full and frank opportunity to reflect on how it came to be in its present position – though one wonders whether the conference next week will be used to have this, or rather to stage manage displays of unity, and to close down dissenting voices. The latter increasing tendency hardly being in the Conservatives’s ‘broad church’ tradition. Hope of talking of ‘ABB’ (Anything But Brexit) and issues that have nothing to do with our relationship with the European Union is all very well. Indeed it is correct that most of the issues that the classic ‘solution in search of a problem’ that the option of leaving the EU was attached to in fact have – well, “nothing to do with our relationship with Europe”. Some circularity there! Secondly, the Conservatives may wish to move on, but they were more than any other mainstream party the origin of the present crisis and things have not actually moved on. It is common in any policy making context, or even at an individual level, to wish to move on from awkward situations and failure. But the nation and society is not there yet much as the Conservatives may wish us to follow the advice – ‘move on there’s nothing to see here’. Thirdly, the desire to move forward to talk of domestic issues and challenges (again regardless of their EU dimension, or otherwise) is understandable, but there was surely a need to mention the paralysis across government and decision making which has been engendered by the effort, time and resources that have been swallowed-up by trying to make sense of a mitigate the impacts of the proposed ‘Brexit’ of the UK from the EU?