Professor David Whyte is part of the Department of Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology.

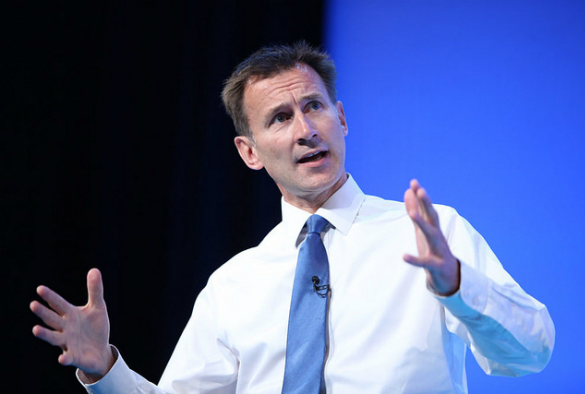

In the midst of the crisis over British diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia following the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the UK foreign secretary, Jeremy Hunt, announced that he intends to appoint British business leaders as ambassadors in the diplomatic service.

You can see how this might play out. Why bother getting a government representative to deal with the Saudi government when you can get a former BAE Systems executive to do the job? Or send a former head of GlaxoSmithKline to China to do the same.

Hunt’s announcement reflects a slightly more extreme version of the neoliberal logic now embedded in diplomatic policy. The support from embassies and consulates that businesses – and their employees – can expect, significantly exceeds support for ordinary citizens.

Since 2010, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) has promised: “To equip its staff with the necessary skills to be effective in supporting UK business and investment, as a core part of the job of the Diplomatic Service.” This includes working to “open the way to greater access for British companies in new markets worldwide” and the “tireless” lobbying of foreign governments to award contracts to British firms. As part of this role, British corporations are regularly invited to accompany government ministers on diplomatic missions.

This exceptional access to diplomatic resources extends to the highest levels of ministerial office. In 2012, the then-chancellor, George Osborne, and the Financial Services Authority begged the US Department of Justice, not to prosecute HSBC for money laundering. Instead, HSBC was hit with a US$1.9 billion (£1.4 billion) fine.

The following year, prime minister David Cameron defended GlaxoSmithKline on an official visit to China when the company was under investigation for a crime that led to a US$490m fine by Chinese authorities. Cameron told the Chinese government: “I know that they are a very decent and strong British business.”

Problems of legitimacy

Hunt’s proposals aim to short-circuit what happens already. The only difference is that appointing former business leaders directly as ambassadors cuts out the need for a government official to play the role of intermediary.

The deeper problem for the legitimacy of the British state is that the government will be much less able to distance itself from companies that engage in questionable practices abroad.

The appointment of business people into key government positions is not unusual in the UK. Labour’s 1997 appointment of BP chief executive David Simon into the cabinet (via the House of Lords) as minister for trade and competitiveness in Europe gave momentum to what is now an accepted practice in government. And of course such appointments are common in the US. Perhaps the most controversial in diplomatic terms was the appointment of ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson as Donald Trump’s secretary of state.

And don’t forget the farcical appointment of Trump himself as one of the Scottish government’s GlobalScot business ambassadors in 2006 – which turned out to be a monumental embarrassment for all concerned. Trump was stripped of this dubious honour in 2015 for his comments against Muslims.

It is difficult to see how the government will be able to recruit business leaders that do not embarrass them. The Department for International Trade already has a list of likely candidates for those jobs. It already engages the services of 48 “Business Ambassadors” who are charged with: “promoting the UK’s excellence, economy, business environment and its reputation as the international trade and inward investment partner of choice.” Some of those on the current list are linked to companies which have been fined for fraud and misconduct.

Hunt’s proposal, then, simply streamlines an enduring logic at the heart of foreign policy: use the channels of diplomacy to defend the right of British corporations to commit crime, then appoint their CEOs as British ambassadors.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.