Barry Godfrey is Professor of Social Justice and Dr Kim Price is a Research Associate in the University of Liverpool’s Department of Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology

Inmates carried out heavy labour in Victorian prisons, and given the stories about the awful food in these prisons, you might assume that they wasted away while they did their time. However, our latest study shows that most convicts were within the normal BMI range at the beginning of their sentence and remained so on release.

When convicts left prison, 80% had the same BMI category (underweight, normal, overweight or obese) they had on entry. And 13% of women and 7% of men saw their BMI category increase.

Prison authorities had to provide a diet with enough calories so that inmates wouldn’t lose weight. After all, they wanted inmates to be healthy enough to find work once they’d done their time. The trick was to provide sustenance as cheaply as possible, but not let anyone become ill from malnutrition. A difficult balancing act.

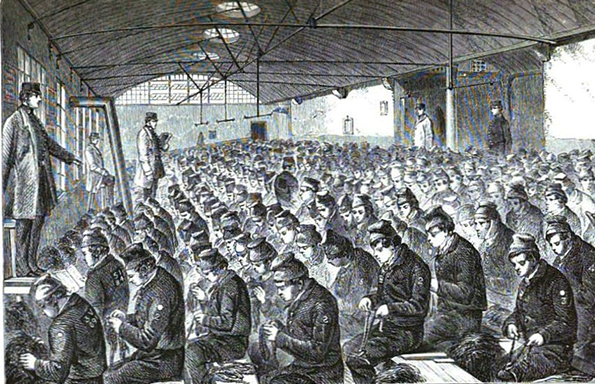

Henry Mayhew, John Binny/Shutterstock

Gruel and stirabout

Diet was an important part of reform and punishment. It was monotonous on purpose, to dull the senses, but it had to keep prisoners alive and capable of carrying out heavy prison labour. Gruel and stirabout were standard dishes.

Gruel needs no introduction, but stirabout was a hated, unpalatable gruel substitute made from cornmeal, salt and oatmeal. (It’s the source of the phrase “doing stir”.) There were, however, daily servings of bread or potatoes – more than we would now expect a person to consume in one day. The prison authorities also insisted that prisoners ate wholemeal bread “prepared as to contain as much as possible of the nutritive properties of the grain”.

Prisoners carrying out hard labour for more than three months received a better diet, supplemented with beef-suet pudding, soup and cocoa, as did some prisoners who were ill (usually more fish or milk).

Burning calories

The system was designed to deter offending through harsh conditions and hard labour. After completing time in solitary confinement, when they were supposed to meditate on their moral shortcomings, convicts carried out arduous physical tasks.

Some activities were useless. Shot drill involved moving a cannonball from one end of the cell to the other repeatedly for hours. Other tasks reduced the financial costs of the penal system; convicts quarried Portland stone, pumped water around the prison on a treadmill (a kind of moving staircase that convicts laboured on for eight hours a day); built dock fortifications at Chatham; unwound heavy tarred navy rope so it could be re-used (oakum picking). Some women worked in the prison laundry; and later, of course, prisoners sewed mailbags.

None of this heavy labour could be done on an empty stomach. The calorific intake had to match the energy expenditure or prisoners would waste away.

Digital Panopticon

For our study, we examined the medical records of more than 400 male and female convicts from the Digital Panopticon, a database of over 90,000 convicts sentenced at the Old Bailey. The records include the weights and heights of prisoners – data that was captured when they transferred to a different prison – something that usually happened five or six times during their sentence.

Surprisingly, the vast majority of male and female convicts maintained the same BMI they entered prison with – many even gained weight – and only a few lost weight.

Convicts served long sentences for committing serious crimes, and they received the standard regulated convict prison diet. Local prisoners serving short sentences for minor crimes were at the mercy of loosely regulated diets of a variable standard, and it showed.

Female convicts serving long sentences had far better BMI ratios than women serving short sentences in local prisons. With an average BMI of 23.9, female convicts even met with today’s “normal” categorisation for BMI. In fact, three-quarters were in today’s normal healthy range (18.5 to 25). A small proportion were overweight or obese, and an even smaller proportion were underweight.

In Victorian England, dietetics was not an exact science and BMI, as we know today, does not always indicate good or bad health. It seems likely that the prison authorities believed they were feeding the convicts in their charge as cheaply as possible but still at a level that ensured they could carry out their hard labour and survive their sentence.

Prison diets in Victorian England did much more than keep inmates alive, they allowed many to gain weight, despite suffering very harsh conditions inside prison.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.