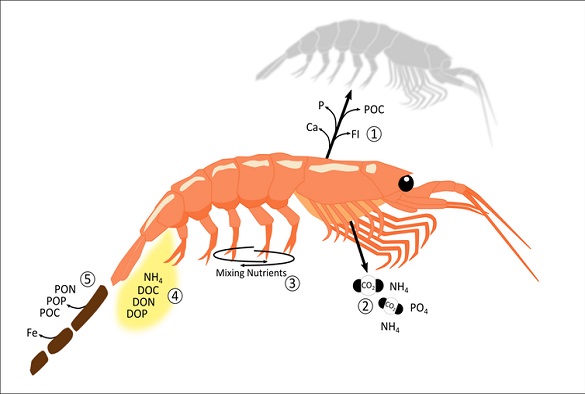

IMAGE: Krill release ammonium (NH4) through excretion and iron in faecal pellets. Pellets also contain a lot of carbon which then sinks to the deep ocean. McCork Studios/Nature Communications, Author provided

This article by Lavenia Ratnarajah (School of Environmental Sciences, University of Liverpool), Emma Cavan (Imperial College London) and Anna Belcher (British Antarctic Society) was first published by The Conversation:

Krill are best known as whale food. But few people realise that these small, shrimp-like creatures are also important to the health of the ocean and the atmosphere. In fact, Antarctic krill can fertilise the oceans, ultimately supporting marine life from tiny plankton through to massive whales and, through their faeces, they can increase the store of carbon in the deep ocean.

In a review we recently published in Nature Communications, we highlighted this less well-known role of Antarctic krill.

Krill are able to fertilise the oceans and help store carbon because they release essential nutrients, including ammonium and iron, into the surrounding water, either excreted as a waste product or in solid faecal pellets. These nutrients can then be used by tiny ocean plants at the base of most marine food webs (phytoplankton) to photosynthesise and grow. This is much the same process as humans adding nutrients to a field through a fertiliser.

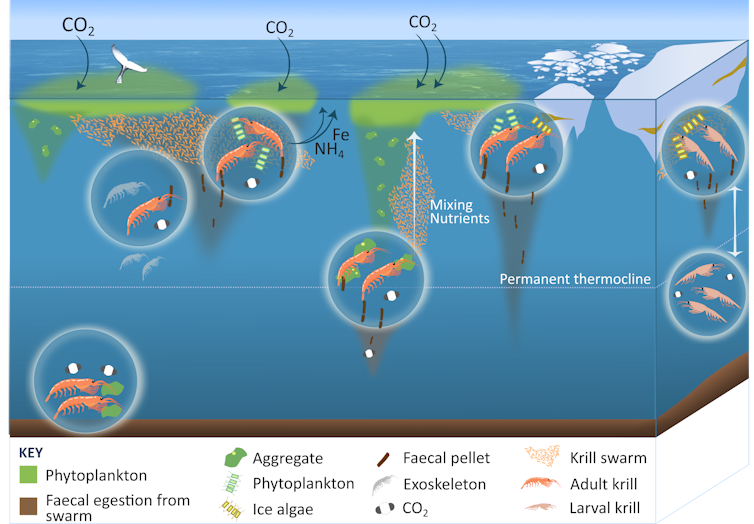

The Southern Ocean surrounds Antarctica and is a long way from landmasses from which nutrients are washed into the ocean. As a result, nutrient concentrations can be low, particularly of iron which is essential for phytoplankton to grow. Concentrations tend to be highest near the Antarctic continent itself, its sea-ice and a few remote islands.

The krill poo carbon sink

Krill waste also influences the carbon cycle. Krill poo is in the form of relatively large, carbon-rich pellets which can sink quickly to the deep ocean where they may remain for many years. This means krill poo can lock carbon away from the atmosphere for long periods of time.

Our synthesis has highlighted that young krill who live near sea-ice may be particularly important in the carbon sink. This is because they live deeper in the water column than adult krill. So any pellets released by younger krill have a better chance of escaping any ocean currents that may return them to the surface, and instead sink further until eventually reaching the deep ocean.

Human impacts to krill and the environment

But what happens when humans disrupt these natural cycles, for example through fishing or causing climate change?

Humans also commercially fish for Antarctic krill – in fact, krill is the most fished animal in the Southern Ocean. Their oily bodies are either used in pharmaceuticals as an alternative source of omega-3, fed to livestock and aquaculture fish, used in pet food or a small amount are even prepared for humans to eat.

McCork Studios/Nature Communications, Author provided

Warming over the past 90 years has meant Antarctic krill have moved south toward sea-ice and fewer juveniles are surviving to adulthood. Given the likelihood that juveniles are also important in the carbon sink it is crucial to ensure that in future fishing boats do not encroach on young krill habitats near the sea-ice.

The krill “fishery” is international, made up of companies from a number of different countries and managed sustainably by international convention – the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources – which sets limits so that only 0.5% of the population is fished in a given year. This ensures that there is enough food in Antarctic waters for whales and penguins, and safeguards the future catch. Scientists and the krill fishery need to work together though to protect nutrient cycles, the carbon sink and the environment. In fact, we believe it is unlikely that any fishery globally considers the impact that removing animals like krill or fish has on nutrient cycles.

We still don’t know exactly how removing krill from the oceans will impact the atmosphere and oceans, and how climate change will further exacerbate this. But one thing is for sure, krill are important in supporting life and storing carbon in the oceans.

Emma Cavan, Postdoctoral Research Associate in Ecosystem Modelling, Imperial College London; Anna Belcher, Ecological Biogeochemist, British Antarctic Survey, and Lavenia Ratnarajah, Postdoctoral research associate, University of Liverpool

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.