Alberto Valdes/EPA

Dr Marieke Riethof is a Senior Lecturer in Latin American Politics in the University of Liverpool’s Department of Modern Languages and Cultures

Chile’s capital city Santiago appears dynamic and bustling, complete with gleaming skyscrapers and a modern metro network. Against the backdrop of the snow-topped Andes mountains, the Costanera Tower – South America’s tallest building – symbolises the country’s open neoliberal economy and mass consumption society.

But protests have rocked the country, challenging this image of stability and prosperity.

Following a government proposal to increase the price of metro tickets, students began to dodge metro fares in protest on October 14, jumping the turnstiles en masse and setting metro stations on fire. The protests soon spread within Santiago and to other Chilean cities, leading President Sebastian Piñera to declare a state of emergency and daily curfews on October 18. This legislation, which dates from the dictatorship era of the 1970s and 80s, allows the military to patrol the streets.

But the move has led to an escalation of the protests, as thousands of Chileans disobeyed the curfews by marching peacefully against government policy and violent repression on a daily basis, calling for Piñera to resign.

The images of soldiers and tanks on the streets, dispersing protesters with water cannon, tear gas, and physical violence, recall the images of military repression during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet between 1973 and 1990. The economic and ideological legacies of the Pinochet era as well as the nature of Chile’s transition to democracy are key to understanding the reasons for the protests. The anger of those on the streets is as much a reflection of the country’s high inequality as it is of these unresolved legacies.

Much of the media coverage of the protests has focused on the spectacle of looting, vandalism, and soldiers beating the protesters. Since the protests started, 18 people have died and there have been 3,000 arrests. But there are wider causes behind these events. The protests emerged in the middle of growing dissatisfaction with high levels of inequality and a high cost of living.

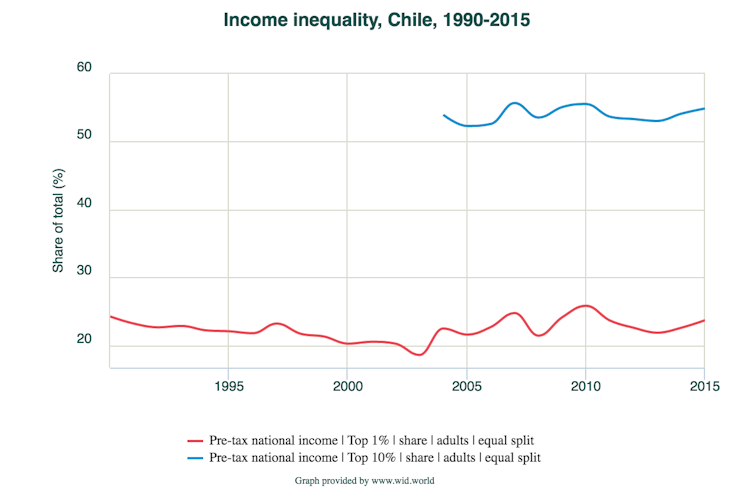

World Inequality Database

On the surface, Chile looks like an economic and political success story, as the country’s GDP growth has outpaced that of Latin America as a whole in recent years, but many Chileans are struggling. The metro fares have come to symbolise what they feel is the unjust distribution of income and social spending.

Legacy of Pinochet era

Like the state of emergency, Chile’s social and economic policies also date from the dictatorship. Neoliberal reforms were introduced in the mid-1970s by Pinochet and his team of American-trained economists, known as the “Chicago Boys”. The reforms took place in the context of violent repression. Official investigations showed that 3,065 people were murdered by state agents during the dictatorship, 40,000 tortured, and hundreds of thousands forced into exile.

The 1970s reforms included the elimination of subsidies, welfare reform, and the privatisation of state-owned companies, the health sector, education and pensions. Pinochet’s reforms led to high levels of unemployment, declining real wages, and expensive social services, such as education. The impact is clear today in education, characterised by low levels of public spending and highly unequal access to good-quality schools and universities. Between 2011 and 2013 students organised mass demonstrations against Chile’s education policies, and dissatisfaction remains.

Chile turned from a military to a civilian government in 1990, following the 1988 referendum in which Pinochet was defeated. But due to the nature of the transition, social and economic policies changed very little. Pinochet negotiated his departure in such a way that the armed forces kept control of the political process, including his own appointment as a lifelong senator. The 1980 military constitution – which is still in place today – has allowed Piñera to declare the controversial state of emergency to deal with the protests. Although some of the military control structures have been dismantled since Pinochet’s death in 2006, the civilian governments on the right and the left have had a limited appetite to address the country’s inequalities.

In response to the protests, on October 22 Piñera suspended the planned fare increases and announced a spending package of reforms to address the protestors’ concerns. The fact that Chileans continue to protest around the country shows that many people feel these measures are too little, too late.

Given the long historical roots of the inequalities, it’s unlikely that one-off extra spending can address the country’s structural problems. Even if the government’s intention has been to de-escalate the situation, its hardline response to the protests signals growing polarisation rather than a quick resolution to the issues.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.