Professor Anna Saunders is Head of the University of Liverpool’s Department of Modern Languages and Cultures

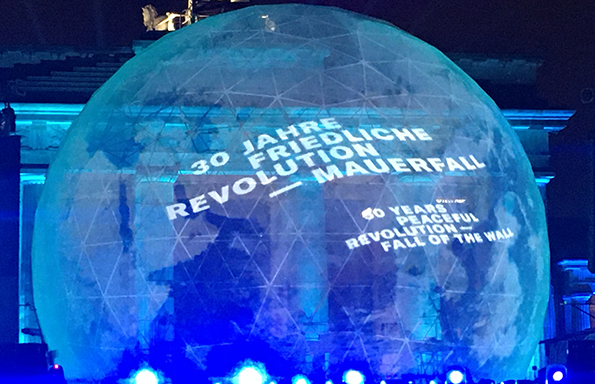

Berlin has just concluded a ‘festival week’ of art installations, performances, exhibitions, talks, tours, workshops and concerts to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall 30 years ago: over 200 events in total. One of the main attractions was the installation ‘Visions in Motion’: a fluttering overhead carpet of 30,000 coloured ribbons, on which Berliners and visitors, young and old, had written their wishes, hopes and visions for the future. It was a mesmerising sight, providing spectacular scenery for the main evening extravaganza at the Brandenburg Gate on 9 November. But what does this tell us about 1989? Is this not too gimmicky – too light on history? It pays to examine the history of this anniversary before passing judgement.

‘Visions in Motion’ in the evening

November 9 is the most fated date in German history. Not only does it mark the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, but also the end of the monarchy in 1918, Hitler’s failed ‘beer hall’ putsch in 1923 and, most prominently, the Pogrom against the Jews, or Kristallnacht, in 1938. Engagement with this date has, thus, been wrought with controversy, and despite proposals after unification to make it Germany’s national holiday, the emotional baggage was considered too great (instead, 3 October was chosen: the official administrative date of unification, which bears little emotional resonance).

Alexanderplatz (with evening video projections of the demonstrations)

Given this history, a celebratory anniversary culture around 9 November 1989 was slow to emerge. In the early years of unification, it was still the memory of the 1938 pogrom that dominated in the public sphere, not least because the newly unified nation felt a need to take responsibility for this past, and unification provided an opportunity to review this history. Also, throughout the 1990s, the reality of life for many in the East – which often included unemployment, economic insecurity and persisting inequalities – meant that 9 November often represented the start of an unfinished, and often unsatisfactory, process of unification.

East Side Gallery (with evening video projections on the Wall)

On the tenth anniversary, for instance, a massive banner was displayed on Alexanderplatz, which provocatively stated ‘Wir waren das Volk’ (‘We were the people’) – in contrast to the dominant chant in 1989 of ‘Wir sind das Volk’ (‘We are the people’). The international focus on the fall of the Berlin Wall as the defining moment of 1989 has also been questioned by former activists: the demise of the German Democratic Republic was a highly complex process that took place over months – if not years – and Berlin was not always at the centre of events. Indeed, the first mass demonstration took place in the Saxon town of Plauen, and the major breakthrough came on 9 October in Leipzig, when it became clear that the regime would not counter demonstrators with violence.

Stasi-HQ

Over the past decade, however, commemorative trends have changed, and the celebration of the fall of the Wall on round anniversaries has become a large-scale and emotionally-charged event. For the twentieth anniversary in 2009, approximately 1,000 huge, painted domino stones were lined up along the course of the Wall and toppled on 9 November; in 2014, nearly 8,000 illuminated balloons mapped the course of the Wall in central Berlin and were released into the sky.

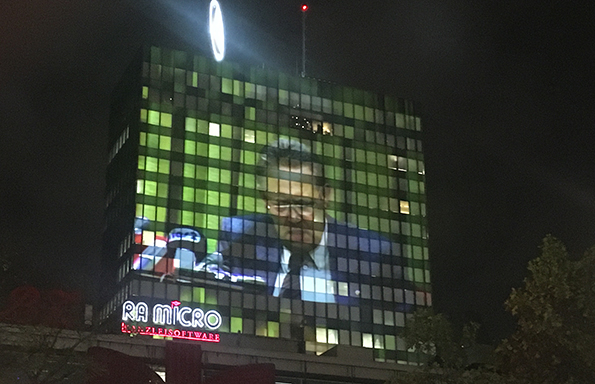

Kurfürstendamm (the only West Berlin location – here with a night-time projection of the now famous press conference with Günter Schabowski)

Like the fluttering overhead carpet of ribbon messages this year, one could argue that such installations have become a clever marketing ploy for the city. There is certainly some truth in this. Yet closer examination also reveals the intention to engage mass interest in this past – often from younger generations who were too young to experience it. Indeed, the emphasis in recent anniversary years has been on widespread participation, often in schools, workshops and public events, through painting the domino stones, sponsoring balloons or writing one’s own message on a ribbon. All these actions encourage personal reflection on, and engagement with, the history of November 9.

Berlin’s Mayor, Michael Müller: ‘Living in freedom means also taking responsibility for freedom’

A sharp awareness of previous historical events has also shaped the development of the anniversary: the achievements of 1989 are always firmly embedded in an international context, and the values of international peace, freedom and democracy are consistently at the forefront of celebrations. This year, event organisers also attempted to profile multiple voices throughout the ‘festival week’, profiling seven different locations across the city, including the former Stasi headquarters and the Gethsemanekirche (one of East Berlin churches to play a central role), both off the beaten tourist track. Exhibition boards and night-time video projections onto buildings told the story of 1989 from the perspective of each location. And while much of this narrative is jubilatory, the difficult process of unification was also highlighted, from revelations regarding Stasi informants, to economic difficulties and right-wing extremism. In the evening ‘show’ on 9 November, references were also made throughout to contemporary problems in Germany and beyond, highlighting the rise of right-wing extremism and the plight of refugees today. As Federal President Steinmeier said in his speech, ‘responsibility for the past does not go away’, and ‘we must fight for this democracy’: 1938 and 1989 are connected in memory.

Final firework display

November 9 will doubtless remain a historically difficult date in Germany, but an anniversary culture is growing. The 2019 anniversary has demonstrated the need to develop pluri-vocal and multi-site commemorative events that recognise the complexities of this history. While participatory installations such as ‘Visions in Motion’ are different from traditional forms of historical engagement, they encourage reflection on the streets: the very place where history was made in 1989.