Peter Andersen is a PhD candidate at the University’s Department of Politics:

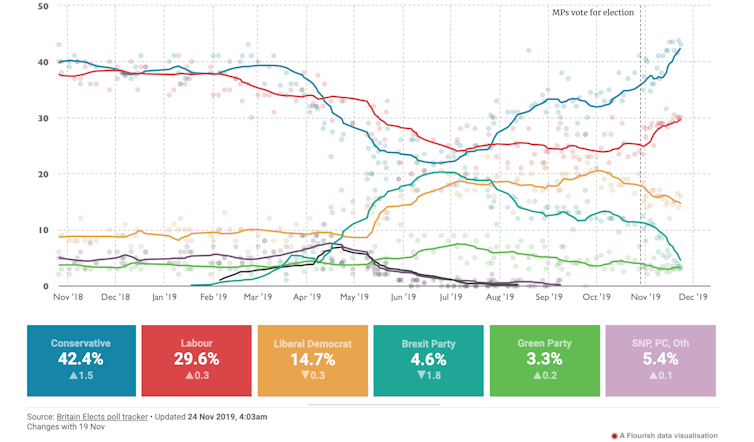

With the 2019 election campaign in full swing, there is little evidence in the polls that things are changing. The overall picture shows both the Conservatives and Labour are both gaining support but the Conservatives remain on track for a majority.

Britain Elects

There have been numerous opportunities for the polls to move in a drastic way. There have been major policy announcements, manifesto launches and several leader debates. Yet little seems to budge, no matter how many times a party leader sticks their hand down the back of the sofa to find another billion for a crowd-pleasing spending pledge.

No wonder so many people are asking: isn’t this campaign a little bit … boring? The Conservatives and Labour are not locked in a tight race for the number one spot. Nothing we’ve seen from the leaders has dramatically changed the way they’re viewed by voters. One of the major parties is not gaining at the expense of the other. Should we expect that to continue? We have significant evidence from the past few elections that shows how much voters really change their mind during a campaign.

How many voters switch?

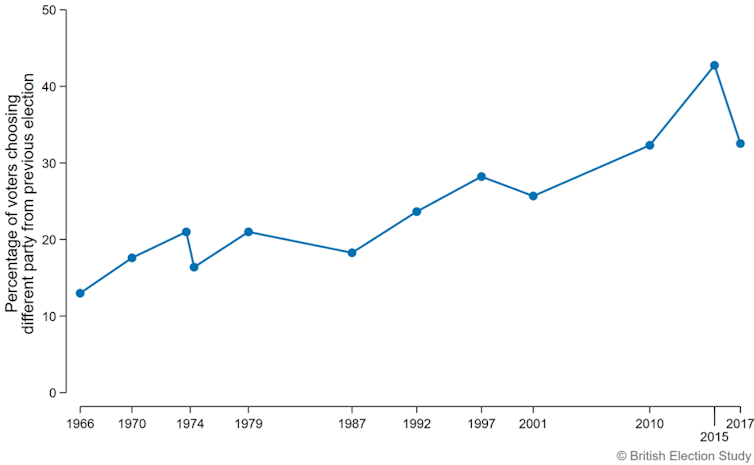

The British electorate is highly “volatile” according to researchers at the British Election Study which begun in 1964. Volatility is measured by the number of voters who choose a different party from one election to the next.

In 2010, 32% of voters picked a different party than the one they voted for the previous election in 2005. Between 2010 and 2015, 43% of voters switched.

However, in 2017, the figure dropped back down to 33%. This lower volatility is particularly interesting given how much political turmoil unfolded between 2015 and 2017, including the EU referendum.

And while these figures suggest we might expect at least one in three voters to switch parties between elections, that doesn’t necessarily mean it will be the campaign itself that changes their mind. They may have already decided to take a different option before the campaign began.

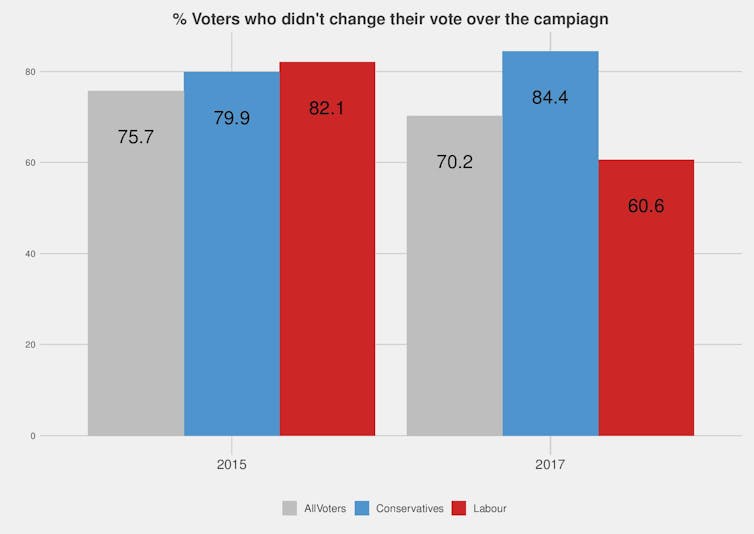

British Election Survey Internet Panel

In 2017, 70.2% of voters stuck with the same party right the way through the campaign. In 2015, that figure was as high as 75.5%. So the overwhelming majority of voters do not change their mind during the campaign – but there is a substantial minority that do.

In 2015 a quarter of voters changed their mind during the campaign. That’s more than enough voters needed to swing the outcome of the election – and yet they didn’t. That’s because these voters didn’t move decisively in one direction. So, while there was a lot of change in individual vote intention, no single party benefited significantly more than the others. It’s also worth noting that stability was higher for the two major parties compared to voters as a whole, with 82.1% of Labour supporters sticking to their party and 79.9% of Conservative voters.

The overall proportion of voters that moved during the 2017 campaign was even higher – and Labour was the key beneficiary. Popular policies, an enthusiastic leader and a dismal showing by then prime minister Theresa May led to noticeable change over the campaign. Nearly 40% of the people who ended up voting for Labour in 2017 had been undecided or intended to vote for another party at the beginning of the campaign. Increased support for Labour in some polls and in the actual results indicates that in some campaigns votes can shift dramatically in favour of one party.

What could happen now?

In all likelihood, the 2019 campaign is affecting the way some people are intending to vote. But because the Conservatives and Labour are both gaining, the broader picture of the outcome of this campaign isn’t changing. The Conservatives appear to be gaining at the expense of the Brexit Party and Labour at the expense of the Liberal Democrats and Greens.

Under the current trajectory both Labour and the Conservatives are convincing similar numbers of voters. Unless there are dramatic revelations in the next couple of weeks, we are unlikely to see a repeat of the dramatic change seen in 2017.

The Conservatives will be happy keeping this campaign as “boring” as possible so long as the big picture doesn’t change between now and polling day. If this campaign is going to be the saving grace for Jeremy Corbyn and Labour, they are rapidly running out of time.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.