Stefan Rousseau/PA Wire/PA Images

Dr Kerry Traynor is a Lecturer in Professional and Media Writing in the University of Liverpool’s Department of Communication and Media

No sooner had the ballots closed than Boris Johnson’s new government was advancing and accelerating its attack on public service broadcasting, threatening to decriminalise nonpayment of the licence fee, boycott the BBC’s flagship Today programme and review the remit of Channel 4.

Labour, meanwhile, has accused the BBC of “conscious” bias, arguing that the corporation’s conduct during the election campaign contributed to Labour’s loss.

While the BBC warned that decriminalisation could reduce funding for programming by up to £200 million, it’s feasible that a much larger proportion of its £3.6 billion licence fee income could be at risk.

One of the key concerns is journalism. Of all the BBC’s output, news and current affairs is the most time-consuming and expensive. The fleeting shelf life of news content – coupled with the costs of maintaining a global network of producers, reporters and researchers – meant that last year the corporation spent £355 million on television news and current affairs programming, more than any other genre of programming.

If the Conservative threats are realised, the capacity of journalists to scrutinise and hold to account MPs, councillors and other elected officials around the country could be severely diminished.

The BBC is already struggling to fund the £5 million annual costs of the Local Democracy Reporter scheme, which pays for around 150 local journalists in local news media to scrutinise local politics.

Before introducing the local democracy scheme, the coalition government of 2010 to 2015 ringfenced £40 million of BBC funding to establish a network of local television news services. It argued the network would play an important role in “the wider localism agenda, holding institutions to account and increasing civic engagement at a local level”. But of the 34 local services established since 2012, at least 12 have failed to launch, collapsed or been merged. The largest local broadcaster, That’s TV, recently closed 13 of its 20 studios.

Reduced scrutiny

Weakened accountability of local politicians chimes with Johnson’s unprecedented avoidance of public scrutiny during the election campaign. This was most notably seen in his refusal to agree to an interview with the BBC’s Andrew Neil, his empty-chairing at the Channel 4 Leader’s Climate Debate, and his hiding in a fridge to avoid an ITV interview on Good Morning Britain.

Sidestepping broadcast journalism enables Johnson to weaken the appeal of public service broadcasting and drive audiences on to social media, where they can be reached directly without interference from journalistic mediators. Johnson’s disdain for the media during the campaign may not be quite on a par with Trump’s tweet of August 5 2018, in which he labelled the media “dangerous and sick” and an “enemy of the people”, but there are clear parallels between the Johnson and Trump strategies.

Plight of local journalism

Local and regional news is particularly vulnerable because, while no less expensive to gather and produce than international news, it attracts small regional audiences and has little export value. Earlier in 2019, the BBC cut regional nightly news bulletins from 11 minutes to seven and the number of staff supporting regional news.

The local newspaper industry is collapsing as readers demand free online news and advertisers find greater reach and targeting on social media. Between 2005 and 2018, there was a net loss of 245 local news titles in the UK. Today, an estimated 58% of the country is not served by a regional newspaper.

When establishing the local television network, then culture minister Jeremy Hunt cited the success of local TV in the US, claiming:

Birmingham Alabama has eight local TV stations, despite being a quarter of the size of our Birmingham. New York has six … It’s crazy that a city like Sheffield doesn’t have local TV.

But a study by the Pew Research Center showed how US local television is only kept afloat by “huge influxes of campaign cash” for political advertising during election and midterm years. In the UK, party political broadcasts are transmitted for free, and strictly controlled.

In other parts of Europe and elsewhere in North America, local journalism is heavily subsidised by the state and through levies on major telecoms companies.

Most Canadian towns have at least one community television service and legislation requires commercial cable broadcasters to support community channels.

In Germany, most cities have a local channel subsidised by the regional government. There, local programming is particularly strong because national broadcasters are not allowed to provide detailed coverage of local issues, so competition is limited for local channels.

In Spain, around 800 local television services have been licensed since the digital switch-over in 2005, with around half funded by local governments and the rest supported by larger media groups.

Post-Brexit broadcasting

Now that a January 2020 Brexit seems certain, one of the most pressing media concerns is whether the UK will continue to align with EU broadcasting standards. Departure from EU alignment could mean more adverts per hour on UK channels, more product placement and a relaxation of the bans on advertising junk food to children.

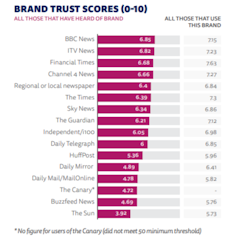

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019.

If the UK adopts the more commercial US approach to broadcasting, the BBC could be forced to accept advertising or shift to a subscription model. Relaxation of the rules on political advertising is a further possibility. Such a move would probably benefit parties with greater spending power, while further damaging – rather than addressing – concerns around the integrity of political communications.

But Johnson might do well to remember that the BBC remains the most popular and the most trusted news source in the UK, across platforms, across generations and across political perspectives, and is well respected worldwide.

Dismantling the nation’s favourite broadcaster is unlikely to be as easy as he might imagine.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.