Professor Mark Viney is the Head of Evolution, Ecology and Behaviour in the Institute of Integrative Biology. He recently visited Bangladesh as part of an ODA Research Seed Fund project investigating parasitic nematode worms.

“We’re driving – well, inching – to today’s field site in Chittagong, Bangladesh’s crowded second city. It feels as if a substantial proportion of the city’s 2.5 million souls are with us on the road.

Parasitic nematode worms are extremely common parasites – about a billion people have worms in their guts, mainly the young or poor of the developing world. The World Health Organization defines these infections as a Neglected Tropical Disease.

We’re heading back to a slum community in the city, where we’ve already found infections with the worm Strongyloides that we’re looking for. This community lies squashed between a main road and the busy river, where drying fish is one of the main activities.

We aim to collect Strongyloides worms from children and dogs, to see whether there is one species of worms infecting both people and dogs, or whether there are two species. This question is both a basic science question – what is the ecological niche of a species of Strongyloides – but also of practical importance. If you want to control Strongyloides infections in people, you need to know where it’s coming from. If it’s coming from dogs then treating dogs has to be part of your control programme too.

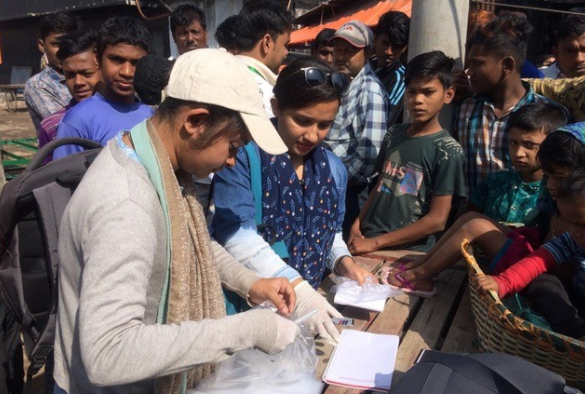

In the community there are dogs everywhere, roving around in small packs, all the while wary of people. I, with two assistants, head off looking for fresh dog faeces, which we’ll take back to the lab. It’s harder to find dog faeces than you’d think – areas on the edge of the communities are the best sites we’ve found. There’s lots of open human defecation too, and telling dog and human faeces apart isn’t always so easy. Colleagues from the University of Chittagong and the Integrated Development Foundation (who run clinics in these communities) are meanwhile working hard to collect faecal samples from children, who are most likely to have Strongyloides.

The community is a busy, thriving community, with a tremendous generosity of spirit (I’ve drunk a LOT of tea!) but clearly very poor. As with all gut worm infections, sanitation is the most effective way to stop worm infections, and when it comes to this community, then worms and other infections should start to disappear – though of course they’ll still be present in dogs.

Back in the University lab we will keep the faeces damp for a few days. If there are Strongyloides infections, then larval stages grow that we then collect. Back in Liverpool we’ll sequence the genome of these worms, so that we can work out the genetic relationship between the parasites in people and dogs.

Today’s work is the first step in our work. Strongyloides occurs in people across the tropics, and in the longer term we need to understand the patterns of infection of Strongyloides in dogs and humans across the world. Now we’re staring at a pile of faeces – human or dog?”

The project was funded by the ODA Research Seed Fund, which has two rounds a year offering researchers up to £10,000 for pilot work, relationship development and other ODA-relevant activities. University of Liverpool staff can find more about it here: