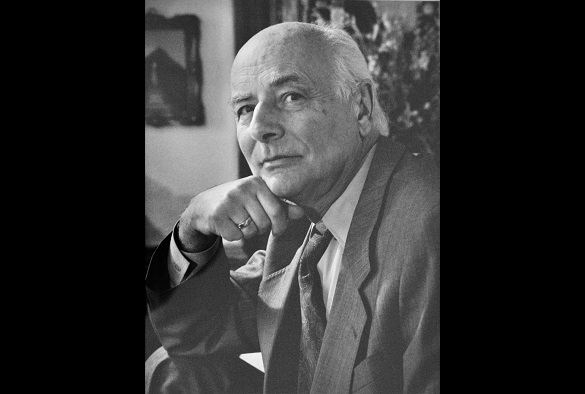

Professor Fred Ridley Photo Credit: Wolfgang Suschitzky

The University is saddened to learn of Professor Fred Ridley’s passing on Thursday, 16 April. Fred Ridley joined the University in 1958 and was Professor and Head of the Department of Political Theory and Institutions from 1965 until his retirement in 1995.

The University’s Associate Pro Vice Chancellor for Civic Engagement, Professor Michael Parkinson CBE has provided a personal tribute for Fred Ridley:

Fred (Fernie to his friends and family) Ridley who has died at the age of 91 was a huge influence on me personally and professionally. I first met him in 1962 when I came as a student to Liverpool’s Department of Political Theory and Institutions, at that time chaired by its first Professor Wilfred Harrison where Fernie was Senior Lecturer. I was equally charmed and intimidated by his elegance and eloquence. The Department then was based in an exquisite Georgian House in Bedford Street North, sadly now a University car park. The Department was tiny. There were only 4 of us in the first year, 6 in the second and a solitary 1 in the final year. He, we subsequently decided without much proof, went on to become a spy. By definition the Department was a small club. Staff and students knew each other well. One of us at the time, Paula Clyne, who was Lady President of the Guild of Undergraduates, later married Fernie. Paula became a significant public figure nationally and locally, not least as Chair of the Victoria and Albert Museum and Tate Liverpool.

Fernie’s mother had wanted him to become an office worker. But Fernie, who had learned English at his kindergarten, insisted he wanted to become ‘educated’, going on to study at the LSE, Paris and Berlin before coming to the Department in 1958 and being made its Professor and Chair in 1965. He taught comparative European politics and public administration and was a convinced Europeanist before it was fashionable, having been a pre-war émigré from the Sudetenland. I still remember his brilliant inaugural Lecture ‘Germany Year 20’ with its literary reference to Isherwood and a world that had incredibly changed. What he would made of a UK post-Brexit world does not bear thinking about!

Fernie was challenging and forced you to think, typically and frustratingly adopting his ‘devil’s advocate’ mode of debate. He was not an easy task master. Still one of my most embarrassing moments is that having missed one of his 9.30 tutorials – no doubt due to drinking the night before – I unfortunately bumped into him outside the Everyman at 1 p.m. that day, where he got to me to admit shamefacedly that one of the rules in those days was that you rang the departmental secretary personally to explain that you would not be present for the Professor’s tutorial! But at least he did not make me appear a total fool by challenging the miraculous recovery which I claimed that I had had from the illness of 3 hours earlier.

Having taught me, Fernie later started my own academic career by offering me a junior research post in the department, after I had done my graduate work elsewhere. He properly began it when he offered me a Lectureship in the Politics department in 1970 which I held for over 20 years. I have no idea what kind of career or life I would have had if he had not done that. So, I always feel he made me. Fernie was capable of acts of great kindness. In the 1970s he helped my family greatly in supporting our wish to remain on leave from UoL working for several years in a University in the USA so we could to continue to receive educational support there for our learning-disabled son, Joey.

Fernie contributed to many spheres of public life. Within the University as only the second Professor the Politics department had had, for 30 years he had an outstanding reputation on comparative public administration. He helped establish it as a top 10, high profile department which attracted many distinguished scholars and visitors. He led it through some politically turbulent times. I recall his fury in 1968 when the University dismissed one of our Politics students for leading the occupation of Senate House over South Africa. He would have been pleased that wrong was righted recently when Peter Creswell was belatedly awarded a degree by this University (https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/politics/blog/2016/pete-cresswell/).

He helped to establish and professionalise the academic study of politics in this country. He was a member of the Political Studies Association (PSA) Executive Committee and the second President of the Politics Association. He was the editor of Political Studies, the house journal of the PSA from 1969 to 1975 and subsequently of Parliamentary Affairs from 1975 to 2004, which he turned into a provocative and challenging journal. Fernie was an excellent if acerbic editor. “This man”, he would say, “has a good point – if only he could make it!” I once offered a manuscript of my own for his reaction. It came back with handwritten alternatives between every typed line of the first page. Unsurprisingly I did not ask him again. Alongside his great academic friend and collaborator Jean Blondel he was an early supporter of the European Consortium of Political Research. Much influenced by the work he did with Blondel on public administration in France, Fernie was a trenchant contributor to the debate about the UK’s ‘non-constitution’.

Fernie also played an important part in the city during the challenging period of the 1970s and 80s. He spoke up for Liverpool and its people during those difficult days of revolts, riots, unemployment and the Militant Tendency. He was Deputy Chair of the Merseyside Manpower Services Commission for most of a decade, the public response at that time to massive unemployment in the city. He received his OBE for that work.

Fernie was the quintessential middle European intellectual, tri-lingual, interested in all aspects of public and political life. He had an extensive cultural hinterland. He was a Trustee of the Museum and Galleries on Merseyside and a sophisticated supporter and patron of the visual arts. He was instrumental in purchasing many of the University’s best paintings of that period and had a very fine personal collection of the leading Liverpool painters at that time, many of whom were personal friends including Adrian Henry, Sam Walsh, Maurice Cockerill, John Baum, Don McKinley and Melvin Chantry. With Paula he kept an elegant but always inviting home – a salon really – where they held interesting and often challenging dinner parties. Their General Election night parties were legendary attracting a diverse collection of friends and neighbours with different party loyalties – guaranteeing robust debate as the wine flowed, the results came in and the winners more or less gently gloated over the losers’ disappointment. Who can forget their legendary Portillo moment in 1997? I won’t. Fran and I were on the verge of leaving the Ridley party at about 3 a.m.when an excited roar went up and we rushed back into the main room to witness the coup de grace for Thatcherism. But we also went to other election night parties where the other side’s star was in the ascendant and we suffered our own defeats. Fernie rather enjoyed provoking both sides in that way.

He was terribly clever. And this made him a less than easy person. He could be a difficult and sometimes infuriating opponent. You could not defeat him, even when he was in the wrong. To complicate life, he was also immensely shy. This made him an occasionally diffident host and slightly difficult guest. He was not averse to sitting silently through dinner and then suddenly announcing someone had been talking rubbish – leaving poor Paula to pick up the pieces. He did not suffer fools – let alone gladly. His tongue could be as sharp as his wit and his brain. This perhaps explains why he did not receive as much recognition as he deserved in later public life. But he was always interesting.

The sharpness of his mind only underlines what a sin it was that the thief of time stole it from him so comprehensively in his later years. These were dreadfully difficult times for him, his friends and his family Francis, Carrie, Dominic and most obviously Paula who bore the burden with great stoicism and evident love.

Fernie Ridley was one of that declining body of people, the European émigré who came and added lustre to the intellectual, political and cultural life of this country – as well as to his adopted city of Liverpool. In a way I am not sorry that he has missed the terrible challenges of Brexit and COVID 19. But he would have been a brilliant interlocuter in both of them. However, the final memory of Fernie I will treasure was at his 80th birthday lunch in his home surrounded by a small number of students who had been with him in the early 1960s avidly reflecting on what had happened to him, us and the world since those halcyon days. In these terrible times, every death is a tragedy. But Fernie’s death for me marks the end of an era. I doubt that I at least shall see his like again. I count myself privileged to have been first his student, then his colleague and at the last his friend for 58 years.