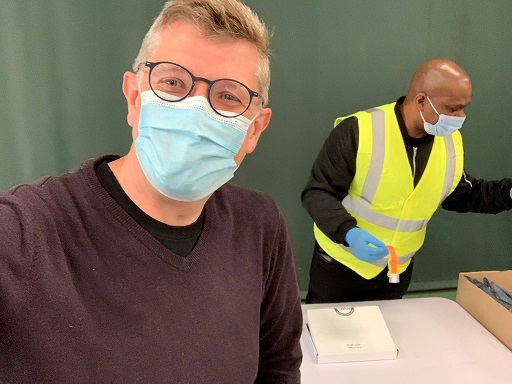

After a momentous weekend in Liverpool, we caught up with Professor Iain Buchan – now officially known as ‘The Party Professor’ – to find out about the Events Research Programme, and how he and teams across the UK will be working together to find out if live, large-scale events can resume safely and securely post-Covid.

Can you tell us a bit about the Events Research Programme?

The Events Research Programme has been a fantastic partnership of a wide National Science group. A lot of people concentrated at the University of Liverpool working in partnership with the local authority, public health teams, event teams, and event organizers to get the data on how to build a safety net around events that involves testing – people have to get tested in the 24 hours before the event.

There’s also a social responsibility piece to that safety shield. People have to declare if they have any symptoms, and not go on the day if they do. For research purposes, we’ve done another two tests. We’ve asked people to take some home tests that are not part of the entry criterion – a PCR test on the event day, and five days later. We’re looking for any signs of virus, but we’re not expecting to see much, because we’re not expecting to see any substantial amount as rates are so low at the moment (around 1 in 1000). So if you apply testing on top of that with lateral flow, they detect at least 8 out of 10 likely infectious individuals. The chance of encountering someone in one of these venues has been exceptionally low, maybe 1 in 5000. It was a mixture of a public health decision – informed by good science – that now is the time to build that safety net.

We’re looking at the early warning system that needs to be in place so that we have all the data, should we need to ramp up later on. If rates were to rise a little bit in July, let’s say, do we have the very quick flow of information between testing, ticketing and event organizers? Do you know who everyone is? Can you trace them quickly? It’s a bit like putting a contact tracing system in place even though you don’t need it. Everyone’s coming to an event, but can the local public health team handle that amount of information in a short period of time? That’s what we’ve really tested – that safety net, and whether the audience understands how important it is that they are part of that safety net. This includes the choices they make, such as minimizing their unnecessary contacts with other people in the days leading up to the event. And afterwards, we can all play our part in securing these events.

Why was Liverpool selected for these pilot events?

Liverpool was selected because it’s been a global pioneer city in testing for people that is voluntary, and irrespective of whether or not they have symptoms. The people of Liverpool embraced the testing scheme with having a larger amount of asymptomatic testing in place. That gives us more intelligence about what the background patterns of the virus are. If you want to understand what events would do to that, you need a lot of background information. Liverpool’s probably the best place in the world to do that.

How did you work with the other organisations in Liverpool to make these events happen?

This is a partnership that’s been growing over the past year, a remarkable partnership of science and society. I’d say it’s one of the most rewarding partnerships of my working life. The events teams and the public health teams in Liverpool City Council have worked with us in the University as just one family. A lot of hard work has been done in a very short period of time, and that’s based on trust, hard work and capability. This was prepared in the community testing program from November. Liverpool already had a plan in December to open events when it was safe to do so when the vaccination scheme was advanced and rates were low. But because of the tight partnership between the University and the City Council and the population, there was the ability to offer a really prepared community for the Events Research Programme.

What has been the most challenging aspect up to this point?

Timescales. Events are complicated – there are a lot of moving parts. If you take public health responding to a pandemic, that’s complicated with a lot of moving parts! You put the two together, and it’s super complex. There’s a lot to consider – consequences of actions that are interconnected in ways that they don’t normally work, ticket offices don’t normally accept health information! They didn’t have a process for doing that, so we had to create processes for the world of events to work efficiently with the world of public health, and to communicate that to both the scientific audience and the public attending the events. Those timescales were the most challenging.

What were your personal highlights of the events that took place over the past week?

I think the finale at Sefton Park with over 5000 people. I’ve never seen a crowd cry happy tears – the event organizers, the participants, the audience broke out into song an hour before the bands came on. There was an outpouring of joy. And suddenly all of the very hard work on the science and the logistics – you could see it was worthwhile. You saw a part of public health that’s about social fabric, mental health and wellbeing just come alive in that room. A GP friend of mine was there, she’s 58. She wanted her teenage twins to go, but they were just under age. She was crying too and it was the most joyous, collective experience I think many of us have ever encountered – and probably will ever encounter. It was major goosebumps time.

So, what happens now?

You have the teams looking at the data coming in, other colleagues in universities in Loughborough, London, and Edinburgh. They’re taking data from sensors from air quality sensors, cameras, and the AI behind the cameras. We’re looking at testing, social media, the usual public health information closely, we’re going to put all of that together. Liverpool is the only place where all the components come into a social critical mass of multiple events happening as they would be. These are realistic events, they weren’t artificial. The Wembley events were not as a big football match would normally be run, but at the nightclub, I can tell you it was pretty realistic because I was terrified! That was full on – the festival was as it would normally be. The business event was as it would have been, so realistic evidence will come out of Liverpool. We will crunch the numbers and deliver a draft report that goes first to Government in May, then fuller public reports come after 11th June. There’s now a ‘Knowhow’ feedback from all the teams who delivered the events being populated and the data needs to be crunched in the next week.

Who will you be working with to analyze the results?

The Institute of Population Health has a great health data science team who take data from an integrated system that we have in Cheshire and Merseyside called CIPHA (Combined Intelligence for Population Health Action). That gives us a feed, so the CIPHA team have been working really hard over the weekend and matching ticketing and testing. We’ll then be marrying the data that comes back from the follow up tests, and they don’t conclude until Friday. They have to be processed by our laboratory in Cambridge – it will be the middle of next week when the full data comes through. The teams have got the ability to flow data from public health, NHS and ticketing into the Institute of Population Health with de-identified secure data. The teams who worked on community testing are the same team, so they are now looking at events and they are used to handling these kinds of data. Marta Garcia-Finana, David Hughes, Chris Cheyne, Girvan Burnside – they’re the team in health data science. Michael Humann in Psychology has bust a gut to deploy questionnaires to eventgoers at military pace. Gary Leeming and teams at the Civic data cooperative have been helping to make sure the data flows work between ticketing and testing. Gary’s worked really hard with his counterpart in events who is the data lead of Robin Kemp. Everyone’s rolled their sleeves up and really worked as one.

What does it mean to be part of the University of Liverpool at this time?

I’m very proud because we’ve delivered on our civic mission and founding principle of ennoblement of life certainly. We’ve made science work very fast, and very deep with social purpose. We looked at the needs of underserved communities, we’ve studied inequalities and Covid-19 extensively. We’re now responding to the need of particularly young people to reconnect in that way that’s important for their formative experiences for their general wellbeing. That has been missing for a very long time. This University has contributed to so many aspects of the COVID response, I’m immensely proud of being at the University of Liverpool.

Anything else you’d like to add?

Yes, I promise to revisit my dress sense in a nightclub! The New York Times sent that tweet out and I’ve acquired a label of the party professor somehow! My friends have laughed their heads off because they know I can’t dance!

On the serious side, the main point I’d like to make is teamwork. I am humbled and delighted by how well the teams across the University of Liverpool, local agencies and city council, NHS and most of all the local community, have just mucked in. There has been 170 years of public health innovation and the spirit of Liverpool is alive and well – just as it was with TB in the 1950s, cholera in the 1800s. There’s a grit, social responsibility and determination that just delivers the generosity of spirit in Liverpool and it’s remarkable.

Discover more

Find out more about Professor Iain Buchan’s Covid-19 work.

Explore the wide range of Covid-19 research work going on at the University of Liverpool.