Researchers at the University of Liverpool are co-authors of a new study of patients with rare cases of blood clots in the brain following COVID-19 vaccination.

The findings provide a clearer guide to clinicians trying to diagnose and treat patients by giving more information about the characteristics of cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) when it is caused by the novel condition vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT).

The observational study was led by University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH) and UCL and is published in The Lancet.

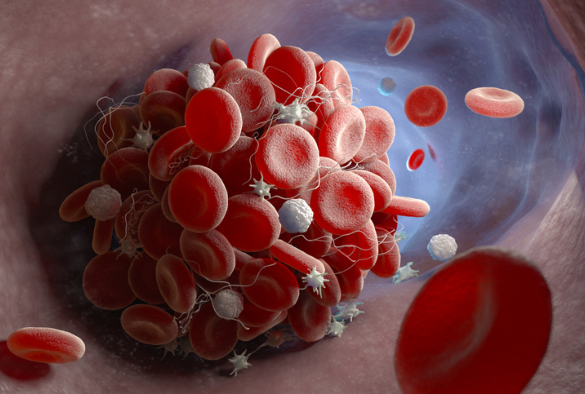

VITT is a condition characterised by a blockage of the veins and a marked reduction of platelets, blood components which are an important part of the blood clotting system.

The commonest and severest manifestation of VITT is CVT, in which veins draining blood from the brain become blocked. The new study provides the most detailed observational study of such cases so far, in which 70 patients with VITT-associated CVT following vaccination are compared to 25 with CVT without evidence of VITT.

The researchers suggest that some treatments such as intravenous immunoglobulin seem to be associated with better outcomes but caution against reading too much into the findings of the observational study, saying that reliable evidence about treatments can only be obtained in a randomised clinical trial.

The NHS’s success with the vaccination programme makes the UK a very good place to study rare side-effects of COVID-19 vaccination. The researchers started collecting their cases within a few weeks of the discovery of this new condition and submitted their report within two months of it being reported in the medical literature.

VITT-associated CVT has a very high mortality rate. Even without VITT, CVT is a very serious medical condition, with around 4% of patients dying during their hospital admission. In patients with VITT-associated CVT observed in this study, though, the mortality rate during admission was around seven times higher than that, at 29%.

This poorer outcome is explained at least in part because the abnormal blockage of veins is much more extensive in this condition, with more veins blocked both in the head and elsewhere in the body.

The study provides support for the three principles of treatment established so far by the Expert Haematology Panel, based on early work at UCLH and two other European sites:

- The use of non-heparin-based anticoagulation

- Give treatments to try to reduce the level of the abnormal antibody that is implicated in this condition, and

- Avoid the strategy of trying to bring the platelet count back up to normal levels by giving platelet transfusions.

Lead author Dr Richard Perry, a consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, said: “With an illness of such severity, often in young patients who were previously fit and well, doctors have been desperate for evidence regarding treatments that might prevent some of the death and disability that arises from this condition.

“While an observational study is not the ideal platform to provide evidence for which medications work, it may be a long time before we have evidence from randomised clinical trials, the gold standard for testing new treatments. For the moment we are dependent on observational studies like CAIAC for our evidence.”

Professor Tom Solomon, a co-author on the paper and a member of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) Vaccine Expert Working Group, said: “Our paper provides the most comprehensive evaluation to date of this very rare side effect from one of the COVID-19 vaccines. By understanding who is most at risk and how they are affected, we can minimise the risk and also optimise their treatment. I think we can be proud that in the UK rather than panicking about such extremely rare events which can potentially derail the whole vaccine programme, we have studied them carefully and modified our approach to vaccination for the overall public health benefit of the whole country.”

Arina Tamborska, a clinical research fellow involved in the project, added: “This paper will greatly advance our understanding of this very rare event occurring after one of the COVID-19 vaccines. It is also a testimony to the UK neurology, stroke and haematology communities coming together at a crucial time to study the condition and positively impact on the UK vaccination strategy.”

Although VITT-associated CVT is a severe condition, it appears to be extremely rare and the researchers stress that, for most individuals, the risk to their health of not getting vaccinated against COVID-19 is likely to be much higher.

Research reference:

Cerebral venous thrombosis after vaccination against COVID-19 in the UK: a multicentre cohort study, The Lancet, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01608-1