The findings of a new study by the University of Liverpool provides further evidence of an approximately 200 million-year long cycle in the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field.

Researchers performed thermal and microwave (a technique which is unique to the University of Liverpool) paleomagnetic analysis on rock samples from ancient lava flows in Eastern Scotland to measure the strength of the geomagnetic field during key time periods with almost no pre-existing, reliable data. The study also analysed the reliability of all of the measurements from samples from 200 to 500 million years ago, collected over the last ~80 years.

They found that between 332 and 416 million years ago, the strength of the geomagnetic field preserved in these rocks was less than quarter of what it is today, and similar to a previously identified period of low magnetic field strength that started around 120 million years ago. The researchers have coined this period “the Mid-Palaeozoic Dipole low (MPDL).”

Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study supports the theory that the strength of the earth’s magnetic field is cyclical, and weakens every 200 million years, an idea proposed by a previous study lead by Liverpool in 2012. One of the limitations at the time was the lack of reliable field strength data available prior to 300 million years ago, so this new study fills in an important time gap.

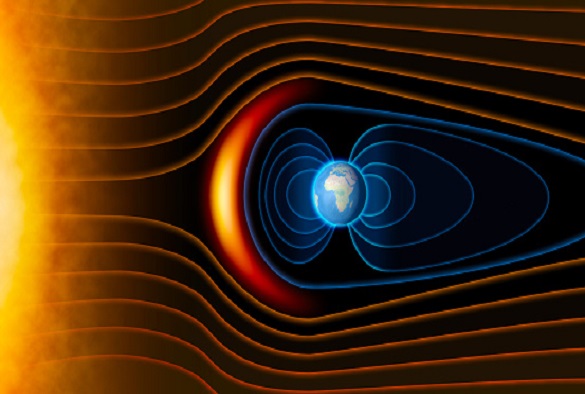

The Earth’s magnetic field shields the planet from huge blasts of deadly solar radiation. It is not completely stable in strength and direction, both over time and space, and has the ability to completely flip or reverse itself with substantial implications.

Deciphering variations in past geomagnetic field strength is important as it indicates changes in deep Earth processes over hundreds of millions of years and could provide clues as to how it might fluctuate, flip or reverse in the future.

A weak field also has implications for life on our planet. A recent study has suggested that the Devonian-Carboniferous mass extinction is linked to elevated UV-B levels, around the same as the weakest field measurements from the MPDL.

Liverpool palaeomagnetist and lead author of the paper, Dr Louise Hawkins, said: “This comprehensive magnetic analysis of the Strathmore and Kinghorn lava flows was key for filling in the period leading up the Kiman Superchron, a period where the geomagnetic poles are stable and do not flip for about 50 million years.

“This dataset compliments other studies we have worked on over the last few years, alongside our colleagues in Moscow and Alberta, that fit between the ages of these two locations.

“Our findings, when considered alongside the existing datasets, supports the existence of an approximately 200-million-year long cycle in the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field related to deep Earth processes. As almost all of our evidence for processes within the Earth’s interior is being constantly destroyed by plate tectonics, the preservation of this signal for deep inside the Earth is exceedingly valuable as one of the few constraints we have.

“Our findings also provide further support that a weak magnetic field is associated with pole reversals, while the field is generally strong during a Superchron, which is important as it has proved nearly impossible to improve the reversal record prior to ~300 million years ago.”

The research is part of the University’s Determining Earth Evolution from Palaeomagnetism (DEEP) group that brings together research expertise across geophysics and geology to develop palaeomagnetism as a tool for understanding deep Earth processes occurring across timescales of millions to billions of years.

DEEP is based in the University’s world class Geomagnetism Laboratory and supported through the Leverhulme Trust and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC)

The paper ` Intensity of the Earth’s magnetic field: evidence for a Mid-Paleozoic dipole low’ is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.