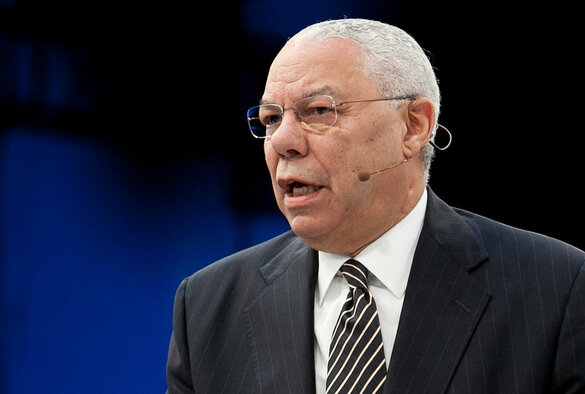

Image by jdlasica licensed under CC BY 2.0

Dr Michael Hopkins is a Reader in American Foreign Policy in the University of Liverpool’s Department of History

The death from COVID-19 complications of Colin Powell on 18 October was yet another sad consequence of the coronavirus pandemic. It marked the end of a great American life. From humble beginnings he had risen through the ranks of the US Army to become Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Secretary of State – and was the first black American to hold each of these posts. His remarkable career confirmed the special qualities he possessed. It revealed how the US Army progressively changed to provide greater opportunities for people of colour. And it demonstrated that it was possible for a decent man to rise to the top in the ruthless upper echelons in Washington.

Colin Luther Powell was born in Harlem, New York on 5 April 1937, the second child of immigrant parents from Jamaica. Growing up in the Bronx he was no more than an average student at high school and at City College of New York. He drifted until he discovered the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps and found a sense of purpose. On graduation from CCNY, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the US Army. With a new-found sense of direction he thrived, enjoying a succession of promotions. He served two tours in Vietnam. In 1972-1973 he held a fellowship at Richard Nixon’s White House. Thereafter, while remaining an army officer, he alternated between military appointments and national security positions in Washington.

He was Deputy National Security Advisor (1987) and then National Security Advisor (1987-1989) to President Ronald Reagan whose successor, George H. W. Bush, appointed him as Chairman of the JCS in October 1989. Powell held the post until he retired in September 1993 after 35 years of service. He had no intention of returning to public office but served as Secretary of State in 2001-2005 when George W. Bush, the son of George H. W. Bush, was elected president.

During his career Powell displayed particular personal qualities and talents. Organised, hard-working, always thoroughly prepared, gregarious, genuinely interested in people, good-humoured, focused on achieving defined outcomes and ready to hear contrary views, he impressed a succession of military commanders and civilian officials with his calm effectiveness. He chose to respond to racist attitudes and behaviour not by protest but by his prodigious achievements. Facing frequent racial slurs and having to serve at military camps located in racially segregated states, he was determined to overcome the challenges. Privately angry at the treatment, he resisted the urge to hit back, declaring, instead, “I’ll show them.” He responded similarly to the less blatant racial tensions he encountered in Washington. His motto was “get mad and get over it,” an attitude he applied to all aspects of his life.

Powell’s reputation, above all, rests on his role in two wars with Iraq.

When Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990 the George Bush administration regarded this aggression as a serious challenge to the world order that required a military response. As JCS Chairman, Powell’s task was to organise military action. From his experience in Vietnam he developed a new strategy – the Powell Doctrine. The country should only wage war in pursuit of clear national interests, that war should involve careful plans for a decisive victory by deploying overwhelming force, and there should be a clear exit strategy. Powell doubted the Iraqi invasion constituted a threat to vital national interests but, once Bush decided to take military action, he persuaded the president to adopt his military strategy. A relentless air campaign targeted the Iraqi military and then a force of 500,000 troops destroyed the Iraqis in a 100-hour war. No attempt was made to follow up military victory with invasion and occupation. Powell became the first US military chief to win a war since 1945.

The second war with Iraq that began in March 2003, when he was Secretary of State, seriously damaged his reputation. Following the terrorist attacks of 9 September 2001, hawks like Vice-President Dick Cheney in the George W. Bush administration urged immediate military action, suggesting Saddam was helping terror groups. Powell shared the concern with Iraq but favoured robust diplomacy and persuaded the president not to act in 2001-2002. By early 2003 he had lost the argument, as the president increasingly listened to Cheney and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. Bush appeared to doubt the value of Powell’s counsel, noting in his memoirs, Decision Points (2010): “it sometimes seemed like the State Department he led wasn’t fully on board with my philosophy and policies.”

Hoping to halt or at least delay the rush to war, Powell acceded to Bush’s request that he address the UN in February 2003. Given only four days to examine CIA intelligence, he accepted their assurances that Saddam possessed weapons of mass destruction. But he was never entirely convinced and suspected he was being used by the White House. War began in March with forces about one-third the size of those deployed in 1991. Iraq was rapidly defeated but troop numbers proved inadequate to the multiple tasks of occupation. By late 2003 there was a serious insurgency. All three pillars of the Powell Doctrine had been ignored. As a loyal member of Bush’s cabinet, Powell accepted that decisions rested with the president but his disenchantment grew, particularly when it became clear that there were no WMD. In early 2004 he signalled his desire to leave the administration. Bush persuaded him to remain until the end of the presidential term in January 2005.

Powell did not write a memoir of his time as Secretary of State, so we lack his detailed account of his role in the Iraq war. He accepted his mistakes, was angry with himself for not detecting the weaknesses in the intelligence, with the CIA, with the hawks and, though he never voiced it, probably with Bush himself. He “got mad then got over it.”