Image by Pimlico Badger licensed CC BY-SA 2.0

Dr Tom Arnold is a Research Associate in the University of Liverpool’s Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place

The Government’s newly announced Integrated Rail Plan (IRP) was, most agreed, a major downgrade on the rail investment promised to Northern England and the Midlands for the best part of a decade.

The eastern leg of HS2 is cancelled, with a high speed service now running only from Birmingham to East Midlands Parkway. Northern Powerhouse Rail (NPR) in its full fat form is no more, replaced by a mix of new line and electrification. Bradford will not get a new high speed service to Leeds and Manchester. A West Yorkshire Mass Transit network is proposed, although as various plans have been in place for a light rail network covering Leeds and its neighbours for almost 50 years, reaction in the region has been understandably sceptical.

The plan is a difficult read. In part, this is because many of the proposals have previously been announced, rendering the Prime Minister’s announcement that it represents the “biggest ever government investment in our rail network” hard to quantify.

Discerning genuine changes to strategic transport policy from post-hoc justifications for abandoning flagship infrastructure schemes is tough work. Hidden amongst the small print is the detail that “commitments will be made only to progress individual schemes up the next stage of development” – even the scaled back projects proposed in the IRP as replacements for HS2 East and NPR are far from guaranteed.

However, draw back from the detail and the plan prompts three key questions.

What does the IRP say about the government’s broader transport agenda?

The IRP is not a plan designed to increase rail travel.

HS2 and, to a lesser extent NPR, were proposed on the basis that capacity on the rail network would need to significantly increase to cope with more passengers and shifting freight traffic from road to rail. Transport for the North (TfN), the statutory planning body responsible for planning NPR, have emphasised the importance of this modal shift in meeting carbon emission targets, projecting that car usage must fall if the UK is to have a chance of achieving net zero.

The IRP suggests the focus will instead be on delivering ‘quick wins’ through electrification and other upgrades to existing lines, recalibrating policy away from a focus on high speed rail and towards local links.

I am sceptical about this approach for several reasons.

First, the plans do little to significantly increase capacity, meaning freight and local services will continue in most cases to use the same lines as inter-city services, with speeds restricted. Some of the most undersold benefits of HS2 lie in its ability to release capacity on other lines.

Second, upgrades to the existing network will be hugely disruptive for passengers, leading some commuters to switch to driving, perhaps permanently.

Third, the plan does not address congestion in and around Manchester, which slows down services travelling through the city, with IRP proposals continuing to rely on an already over-burdened Piccadilly station.

Fourth, a key aim of high speed rail is to reduce domestic air travel, an objective that is barely mentioned in the IRP and will not be achieved with piecemeal improvements.

And finally, electrifying rail lines should be considered a basic upgrade to ancient infrastructure, not a fundamental part of an ambitious transport plan. Much of the Transpennine electrification heralded in the IRP was first announced in 2011.

Ultimately, the cuts to previously agreed infrastructure proposals are a result of the Treasury’s innate institutional caution, bolstered further by Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s reluctance to increase government borrowing.

As the New Statesman’s Stephen Bush points out, Sunak’s decision to impose a limit of 3% of GDP on infrastructure spending makes it difficult to achieve the level of investment needed to transform the UK’s ageing, carbon-intensive transport network. Despite changes to the Green Book in 2020 which were designed to encourage a shift away from the myopic focus on cost-benefit analysis that had long characterised transport spending decisions, the Treasury remains a formidable block on public investment.

The IRP represents a continuation of British transport policy over several decades that sees infrastructure primarily in terms of demand management and fiscal restraint rather than as a tool of economic and environmental transformation.

What next for Transport for the North?

The cancellation of HS2 East and NPR represent a major blow to Transport for the North (TfN).

The organisation was established in 2015 and set the task of developing a transport plan to promote economic rebalancing, create a ‘single economy’ in Northern England, and connect cities and towns to allow them to be “stronger than the sum of their parts”.

TfN’s original plan for NPR focused on reducing rail times between Manchester, Leeds and Sheffield, but the development of a significant economic evidence base and extensive lobbying by West Yorkshire Combined Authority led to the inclusion of Bradford in its ‘vision’ for the high speed network (below), published in its 2019 Strategic Transport Plan.

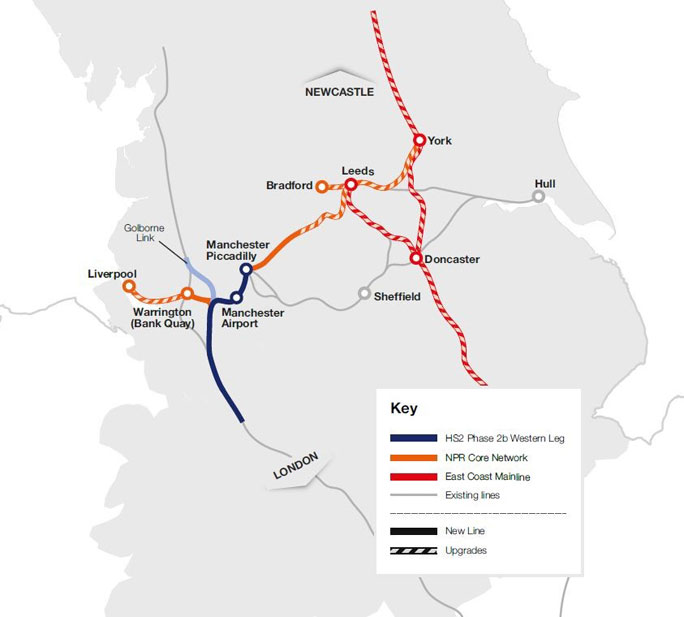

Northern Powerhouse Rail ‘emerging vision’, including new high speed lines between Liverpool and Manchester, and Manchester and Leeds via Bradofrd (Transport for the North, 2019)

Northern Powerhouse Rail is TfN’s totemic project.

The organisation’s extensive investment in economic appraisal and modelling was designed to develop a bulletproof case for investment that would be transformational – “more than an infrastructure project…a social and economic catalyst for the region”.

TfN has delivered some impressive work, acting as a de facto economic agency for Northern England as well as a transport body, particularly through the Northern Powerhouse Independent Economic Review. The mayors and local authority leaders who sit on the TfN board may now be wondering, however, what the point of it is if government can simply ignore plans that have been five years in the making.

Together with government’s apparent cooling on sub-national institutions over recent years, it is hard to be optimistic about the future of Northern England’s sub-national transport body.

The new NPR ‘core network’ proposals, showing a mix of upgrades and some new line (IRP, 2021)

Is Levelling Up over before it began?

Levelling Up has long appeared a catchphrase in search of some policies, but the focus of the agenda appears clearer than it did a few months ago.

Now in charge of the new Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, Michael Gove has highlighted a focus on four areas: local leadership, living standards, public services and ‘pride of place’. Notable in its absence, and in contrast with earlier attempts to inject energy into tackling the UK’s wide interregional disparities, is transport infrastructure.

The IRP represents the latest evidence of a clear move away from significant capital spending on megaprojects, and towards smaller scale investments.

The Levelling Up Fund, for example, only provides funding for projects worth up to £20m, with an emphasis on those that can be delivered quickly. Similarly, the Towns Fund offers up to £25m for successful bids.

While sprucing up high streets, building leisure centres and installing more bins are laudable enough projects, these were the types of regeneration activity until recently routinely delivered by local authorities.

This level of investment is unlikely to contribute significantly to rebalancing the economic geography of the UK – “the greatest project any government can embark on”, according to the Prime Minister in his Conservative party conference speech earlier this year.

There is a legitimate argument that voters will appreciate improvements to their local environment – parks, public services and other amenities – more than new rail lines they may not use for another 20 years, if at all. However, the economic, social and environmental challenges facing the UK over the coming years make investment in transport infrastructure imperative.

The UK’s commitment to achieve net zero by 2050 will not be achieved without shifting journeys from air and road to more carbon-efficient forms of transport, even if electric cars become ubiquitous over the next decade.

England’s cities outside London are poorer and less productive than they should be, with weak transport connectivity a major contributor. Freight and distribution networks will need to be enhanced in the UK’s post-Brexit trading environment.

The IRP represents a blow for those who believe infrastructure investment is not only effective in improving economic and social outcomes, but also prudent.