Image by Valeri Fortuna is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Costas Milas is Professor of Finance in the University of Liverpool’s Management School

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) sets interest rates with the aim of bringing two-year ahead Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation back to the 2% target. The Bank of England, however, is not a ‘strict inflation targeter’. This is because setting interest rates with the sole aim of keeping inflation under control risks undermining economic growth.

When the Bank was granted operational independence over monetary policy by (New) Labour (led by Tony Blair) in 1997, it understandably followed a stricter policy of inflation targeting. Indeed, in earlier work, Professor Chris Martin and I found that the Bank’s MPC members adopted “asymmetric” monetary policy targeting In particular, rather than attempting to hit the 2.5% inflation target (based on the targeted, at that time, Retail Price Index minus mortgage interest rate payments measure of inflation) they pursued a policy of “zone” targeting. That is, they were very keen to raise the Bank’s interest rate when inflation exceeded 2.6% or cut the policy rate when inflation fell below 1.4%.

In other words, the Bank, during its early years of operational independence, was very keen to establish its anti-inflationary authority by “going tough” on inflation when the latter exceeded 2.6%. On the other hand, during these early years, the Bank did not see (very) low inflation as an urgent matter to respond to.

What is the current situation with UK interest rates in light of rising inflation? The Bank expected (in November 2021) CPI inflation to peak at 5% in the second quarter of 2022. The Bank also expected inflation to remain well in excess of the 2% target whether, in line with financial market expectations, it raised its policy rate to 1.1% by the end of 2023 or, instead, decided to take no interest rate action up until 2024!

Even worse, Ben Broadbent, Deputy Governor of the Bank and an MPC member, noted one month later (in December 2021) that UK inflation is likely to soar “comfortably” above 5% in spring 2022. Inflation well in excess of 5% definitely puts the Bank of England under additional pressure to act swiftly even if rising prices are (mainly) due to supply-side bottlenecks. Needless to say, it also raises unpleasant questions about the Bank’s forecasting ability.

All this raises the important issue of why the Bank of England is not taking (strong) action against rising inflation. In other words, has the Bank of England given up on inflation? The answer relates, of course, to the impact of the pandemic and the emergence (in late November 2021) of the “Omicron” variant.

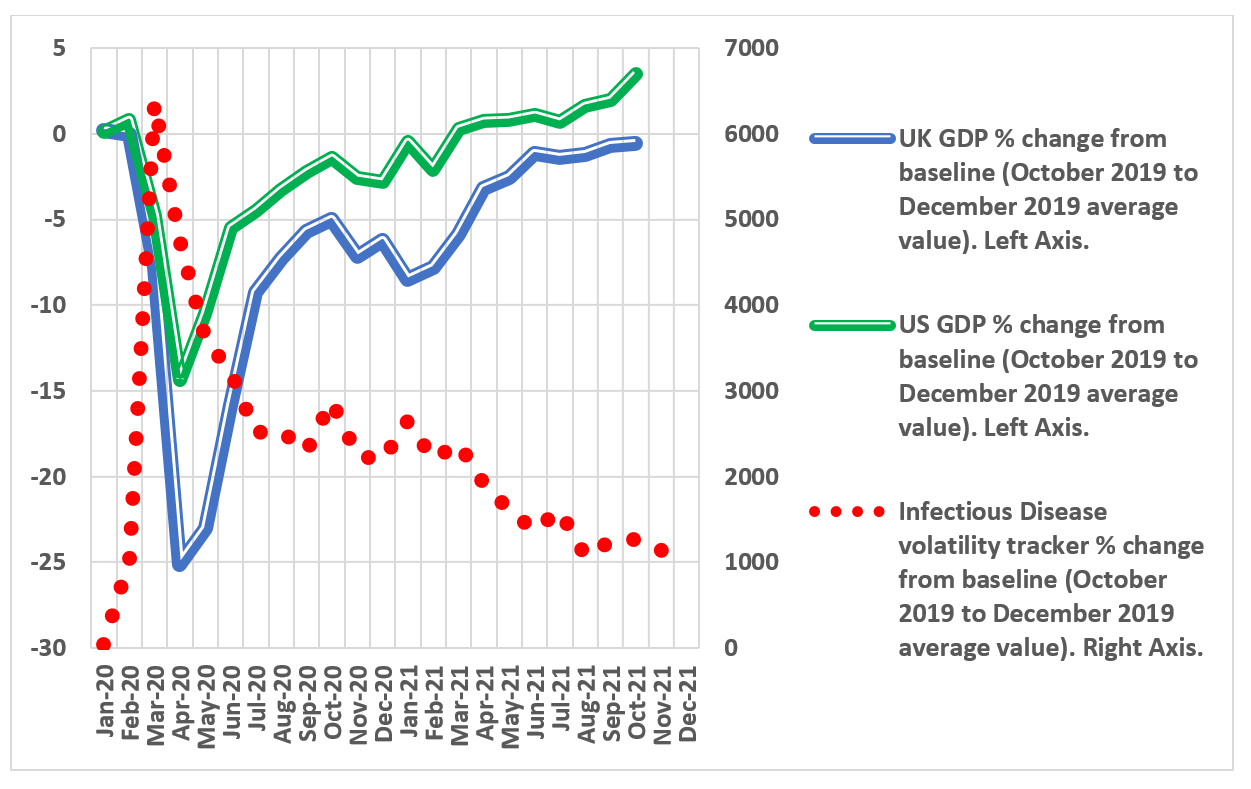

The pandemic consequences for the UK economy can be seen in Figure 1, which plots UK GDP (% change from its pre-pandemic value) together with the so-called “Infectious Disease Equity Market Volatility Tracker” (% change from its pre-pandemic value). The latter index tracks articles discussing economic/financial uncertainty as well as infectious diseases in a large number of US newspapers. In December 2021, the Infectious Disease tracker was slightly on the rise, mainly due to concerns about the new “Omicron” variant and its ability to evade, to some extent, vaccines. UK GDP data are published with a delay. According to the latest data, GDP recorded a month-on-month growth of only 0.1% in October 2021. Consequently, UK GDP remained, in October 2021, 0.6% below its pre-pandemic level.

From Figure 1, there is a strong and negative correlation (equal to -0.70) between the two variables. The ongoing pandemic exerts a negative impact on UK growth, which understandably makes MPC members less willing to act on inflation because a series of interest rate hikes could “derail” economic recovery. The Infectious Disease Volatility tracker is international in nature and therefore exerts worldwide effects.

Again from Figure 1, US GDP stood, in October 2021, 3.5% above its pre-pandemic level. Notice also the inverse relationship between the tracker and US GDP (correlation equals -0.73) which suggests that further increases in the tracker due to the ‘Omicron’ variant will also undermine economic recovery in the US and, consequently, the rest of the world (including the UK) since global growth is influenced by growth in the US.

Figure 1. UK GDP, US GDP and Infectious Disease Volatility tracker (% change from pre-pandemic period for all three series). Monthly data.

Data sources: UK GDP: ONS; US GDP: IHS Markit; Infectious Disease Volatility tracker: Economic Policy Uncertainty

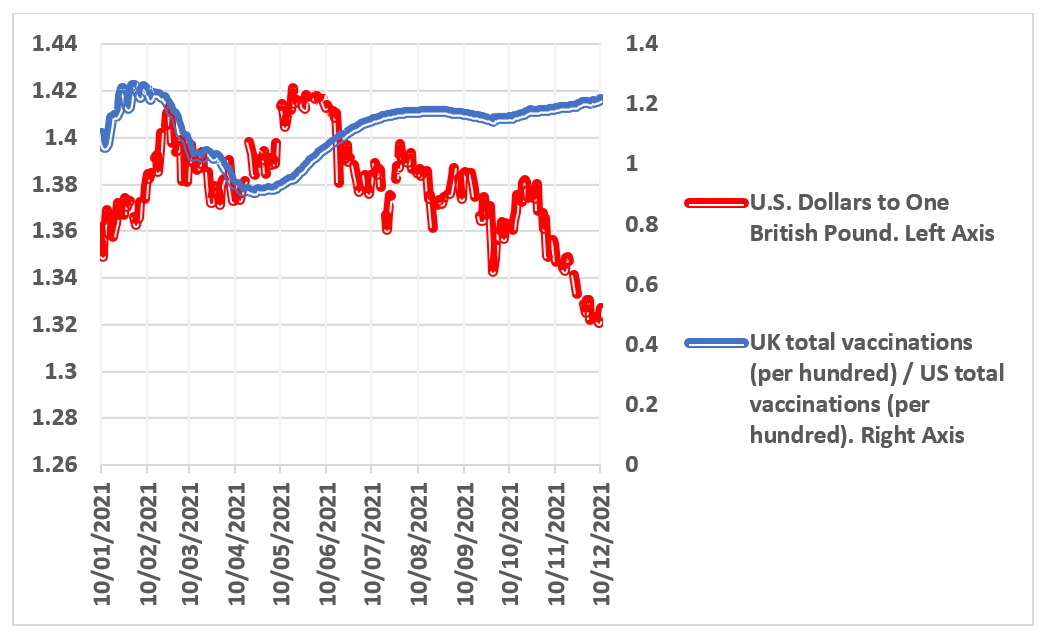

Notice also that the Bank’s job has definitely been complicated by the recent fall in the sterling exchange rate, which adds additional pressure on inflation. For parts of 2021, the successful rollout of the UK vaccination programme has provided a welcome shot in sterling’s arm, which contained, to some extent, UK inflation. Not anymore, as can be seen from Figure 2, which plots sterling against the dollar and the rollout of the UK vaccination programme relative to the one in the US. From Figure 2, the vaccine rollout in the UK is still going well, but as David Smith (Economics Editor of The Sunday Times) noted, “sterling’s vaccination boost has faded”.

Boris Johnson has just announced the government’s plan to throw everything at beating ‘Omicron’ by speeding up the booster rollout. This is likely to have the welcome economic side effect of strengthening sterling and slowing down to some extent the surge in inflation.

Figure 2. Sterling and the rollout of the vaccination programme. Daily data, January-December 2021

Data sources: Sterling: FRED Economic Data; Rollout of vaccination programme: Our World in Data

All these, in light of the emergence of the “Omicron” variant and additional COVID-19 restrictions announced by Boris Johnson on 8 December 2021 make it extremely likely that the Bank of England MPC members will delay a rise in UK interest rates despite the surge in inflation. In other words, the Bank of England has not given up on inflation. Although “Omicron” worries have taken over, the UK economy has adapted well to past Covid-19 restrictions which arguably suggests only a slight delay in interest rate hikes…

This article first appeared in LSE Business Review, to read the original article please visit https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2021/12/14/has-the-bank-of-england-given-up-on-inflation/