This article written Colin Irwin, Department of Politics, was originally published in The Conversation.

The talks aimed at ending the violence in Gaza are failing because there is no guarantee any ceasefire negotiated at present will last. Hamas wants a permanent ceasefire leading to the establishment of a “fully sovereign” Palestinian state. The Israeli government – particularly the more rightwing nationalistic elements – wants Hamas destroyed completely. It’s not clear these conflicting positions can be reconciled.

Insurgencies can be defeated by eliminating the insurgent militarily, or by effectively addressing the grievances that prompted them to take up arms – or a combination of both. This means continuing conflict while negotiating a peace deal in good faith.

In Northern Ireland, the British were persuaded to do both and it worked. In Palestine, Israel uses force with considerable effect – but in the absence of peacemaking, this force is counterproductive. The grievance remains unaddressed and the insurgency grows.

In his 2023 address marking the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, US senator George Mitchell rightly pointed out that without John Hume, there would have been no peace process, and without David Trimble, there would have been no peace agreement. Both received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1998: Hume for persuading Sinn Fein and its military wing, the Provisional IRA, to pursue a constitutional path to peace, and for bringing in the US as peace brokers.

As a result, the then-US president, Bill Clinton, took up this initiative and persuaded the British to do likewise. The Northern Ireland secretary, Peter Brooke, declared that the British had no selfish or strategic interests in Northern Ireland, ceasefires were agreed, and an effective, inclusive peace process was implemented.

That peace process was not easy. It took the combined political effort of the Irish and British governments, the US presidency and the EU to get there. But peace was achieved, and with Sinn Fein now sharing power with the other constitutional parties in Northern Ireland, the insurgency no longer has such a grievance. It seems unlikely that Northern Ireland will go back to war.

Can Israel do the same? I believe so. I came to this conclusion when I met with Hamas on December 3 2008, while making preparations for Mitchell to start work as newly elected US president Barack Obama’s special envoy for Middle East peace.

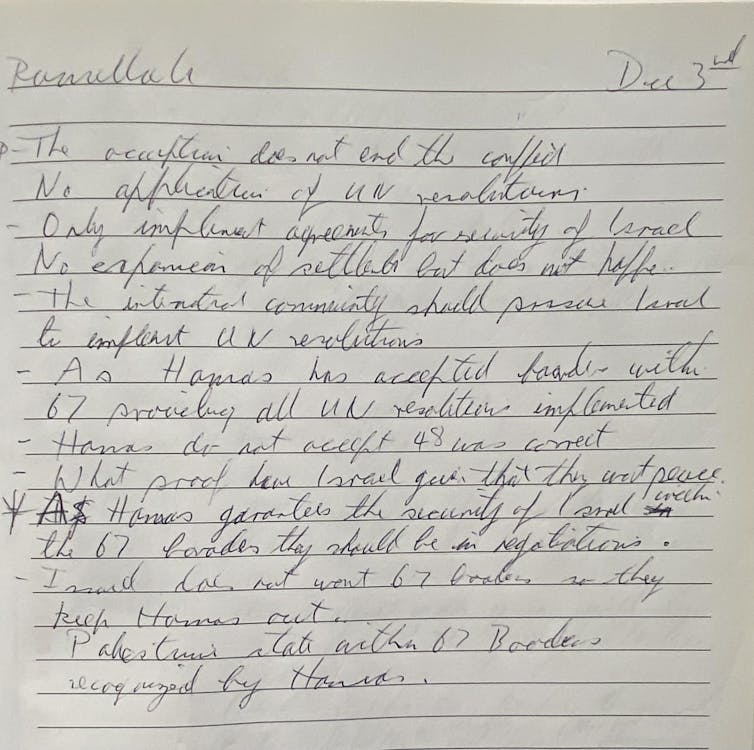

In the image below are the notes I took during that meeting in Ramallah – a series of bullet points summarising the Hamas negotiating position.

Colin Irwin, CC BY-SA

They show that Hamas was serious about a peace process. It was prepared to guarantee the security of Israel, and accept a Palestinian state within the internationally recognised borders following the war of 1967.

It also reflects a degree of scepticism about Israel’s willingness to negotiate in good faith, and frustration at the failure of the international community to fully implement UN resolutions aimed at bringing peace to the region.

But it shows Hamas was ready to engage. Political organisations such as Sinn Fein and Hamas have good intelligence, so Hamas would have known before I met them all about me, and my role in running public opinion polls in Northern Ireland to gauge sentiment on all sides prior to forging the Good Friday Agreement.

From our meeting, it was clear that Hamas was willing to be part of an inclusive peace process when Mitchell took up his post in 2009.

Accepting change

Paramilitary organisations such as Sinn Fein and Hamas have to bring their followers with them on the difficult journey to peace. On this point, I was able to help Sinn Fein deal with a critical problem which has also been a problem for Hamas: its constitution.

Sinn Fein’s constitution prohibited it taking seats in a Northern Ireland assembly – it could only participate in a parliament that represented a united Ireland. So, arguably, it had negotiated the Good Friday Agreement in bad faith.

To help fix this problem, we drafted and ran some questions that clearly demonstrated that Sinn Fein voters wanted their own representatives in the new Northern Ireland assembly, along with everyone else. On the back of this result, Sinn Fein called a special Ard Fheis (general meeting) and changed its constitution so it could agree to and endorse the Good Friday Agreement.

When I met with Hamas in 2008, I was certain that, given the opportunity – and the prospect of gaining legitimate constitutional power – Hamas would have done the same, and accepted the two-state solution.

Mahdi Abdul-Hadi, director of East Jerusalem-based thinktank the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, helped set up my first meeting with Hamas in 2008. When I saw him again in Jerusalem in May this year, he told me there are now “two Hamas”. Since I was there in 2008, it has split into the Gaza faction under Yahya Sinwar, and the political bureau led by Ismail Haniyeh in Qatar.

Sinn Fein and the Provisional IRA had to confront a similar issue during the Northern Ireland peace process, with the breakaway group that called itself the Real IRA. But with the success of Sinn Fein as a constitutional political party sharing power, the Real IRA is no longer a significant threat.

Sadly, the failure of the Israeli peace process in 2009 has led to a very different outcome: 1,200 Israeli dead on October 7 last year, and 37,000 and counting Palestinian dead since then.

On October 18 2023, the US president, Joe Biden, advised the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, not to repeat the errors the US had made after 9/11. He might also have suggested Netanyahu learn the lessons of Northern Ireland and make peace with his Palestinian neighbours.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.