University of Liverpool researchers are part of an international physics experiment that has just announced its record-breaking latest results in the search for dark matter.

The LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment is dedicated to uncovering the secrets of dark matter, the elusive substance thought to constitute 85% of the universe, and a central challenge in modern physics.

LZ is the world’s most sensitive dark matter detector, bringing together 250 scientists and engineers from 37 institutions, including a key team from the University of Liverpool’s Department of Physics.

Led by the USA Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the LZ experiment operates almost one mile underground in the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota, hunting for traces of dark matter in unprecedented detail.

The newest results from LZ extend the experiment’s search for low-mass dark matter and set world-leading limits on one of the prime dark matter candidates: weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs.

They also mark the first time LZ has picked up signals from neutrinos from the sun, a milestone in sensitivity.

The new results use the largest dataset ever collected by a dark matter detector and have unmatched sensitivity.

The analysis, based on 417 live days of data that were taken from March 2023 to April 2025, found no sign of WIMPs with a mass between 3 GeV/c2 (gigaelectronvolts/c2), roughly the mass of three protons, and 9 GeV/c2.

It’s the first time LZ researchers have looked for WIMPs below 9 GeV/c2, and the world-leading results above 5 GeV/c2 further narrow down possibilities of what dark matter might be and how it might interact with ordinary matter.

The results were presented today in a scientific talk at SURF and will be released on the online repository arXiv. The paper will also be submitted to the journal Physical Review Letters.

Liverpool’s role

Liverpool physicists have been part of the LZ collaboration since 2014, providing significant technical, hardware and software expertise to the experiment.

Led by Professor Sergey Burdin of the Particle Physics Group, they played a key contribution to these latest results.

The Liverpool team maintain and operate the Optical Calibration System (OCS) for the LZ Outer Detector, which was produced with support from the Detector Development and Manufacturing Facility.

In addition, Dr Ewan Fraser, together with postgraduate and undergraduate students, develops sophisticated machine-learning algorithms for data analysis, calibration and detector monitoring. He also leads the Data Quality group, which is essential for understanding detector effects.

Professor Burdin said: “The exceptional performance of the LZ detector and the extensive work on its calibration and data analysis enabled us to reach unprecedented sensitivity. As a result, LZ observed the strongest evidence to date of boron-8 solar neutrinos interacting with xenon atoms via the rare coherent elastic neutrino–nucleus scattering process. Although this is not a dark-matter signal, its observation — and its agreement with theoretical predictions — is essential to validate the detector’s sensitivity.

“This process, nicknamed the ‘neutrino fog’ (also referred to as the ‘neutrino floor’), will be one of the main limiting factors for next-generation dark-matter searches, so understanding it is crucial. We are using our hardware and software expertise to design the next-generation experiment, which will extend sensitivity to dark-matter particles down to the neutrino-fog limit across a wide range of masses.”

The boron-8 solar neutrino

LZ’s extreme sensitivity, designed to hunt dark matter, now also allows it to detect neutrinos — fundamental, nearly massless particles that are notoriously hard to catch — in a new way. (Fittingly, LZ sits in the same underground cavern where Ray Davis ran his decades-long, Nobel Prize-winning experiment on neutrinos).

The analysis showed a new look at neutrinos from a particular source: the boron-8 solar neutrino produced by fusion in our sun’s core. This data is a window into how neutrinos interact and the nuclear reactions in stars that produce them. But the signal also mimics what researchers expect to see from dark matter. That background noise, sometimes called the “neutrino fog,” could start to compete with dark matter interactions as researchers look for lower-mass particles.

The boron-8 solar neutrinos interact in the detector through a process that was only observed for the first time in 2017: coherent elastic neutrino-nucleus scattering, or CEvNS. In this process, a neutrino interacts with an atomic nucleus as a whole, rather than just one of the particles inside it (a proton or neutron). Hints of boron-8 solar neutrinos interacting with xenon appeared in two detectors last year: PandaX-4T and XENONnT. Those experiments were shy of the standard threshold for a physics discovery, a confidence level known as “5 sigma,” reporting 2.64 and 2.73 sigma (respectively). The new LZ result improves the significance to 4.5 sigma, passing the 3-sigma threshold that is considered “evidence.”

While the background signal from neutrinos presents challenges for the dark matter detector at low masses (3-9 GeV/c2), its new secondary role as a solar neutrino observatory gives theorists more information for their models of neutrinos, which still hold many mysteries themselves. LZ can provide an independent measurement of how many boron-8 neutrinos are coming from the sun (known as “neutrino flux”), detect future neutrino bursts to better understand supernovae, and help study one of the fundamental parameters that describe how particles interact (the weak mixing angle).

Reaching into the neutrino fog also highlights LZ’s performance, with the ability to sense incredibly tiny amounts of energy from individual particle interactions.

Next steps

LZ is scheduled to collect over 1,000 days of live search data by 2028, more than doubling its current exposure. With that enormous and high-quality dataset, LZ will become more sensitive to dark matter at higher masses in the 100 GeV/c2 to 100 TeV/c2 (teraelectronvolt) range. Collaborators will also work to reduce the energy threshold to search for low-mass dark matter below 3 GeV/c2, and search for unexpected or “exotic” ways that dark matter might interact with xenon.

Many of the researchers from LZ are also designing a future dark matter detector that uses liquid xenon on an even larger scale.

The XLZD detector will combine the best technologies from projects like LZ, XENONnT, and DARWIN for a next-generation WIMP hunter that can also study neutrinos, the sun, cosmic rays, and other unusual candidates for dark matter, such as dark photons and axion-like particles.

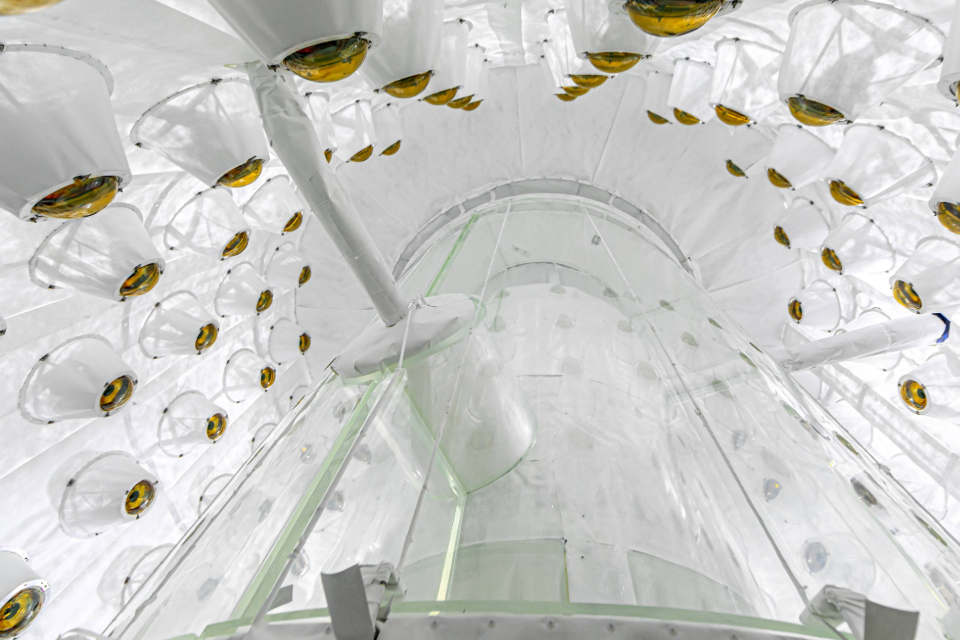

Image caption: Looking up into the LZ outer detector, used to veto radioactivity that can mimic a dark matter signal.

Credit: Matthew Kapust/Sanford Underground Research Facility