Research from the University of Liverpool has revealed that our Palaeolithic ancestors enjoyed vegetarian meals and cooked up sophisticated, flavoursome recipes including flatbread-like items.

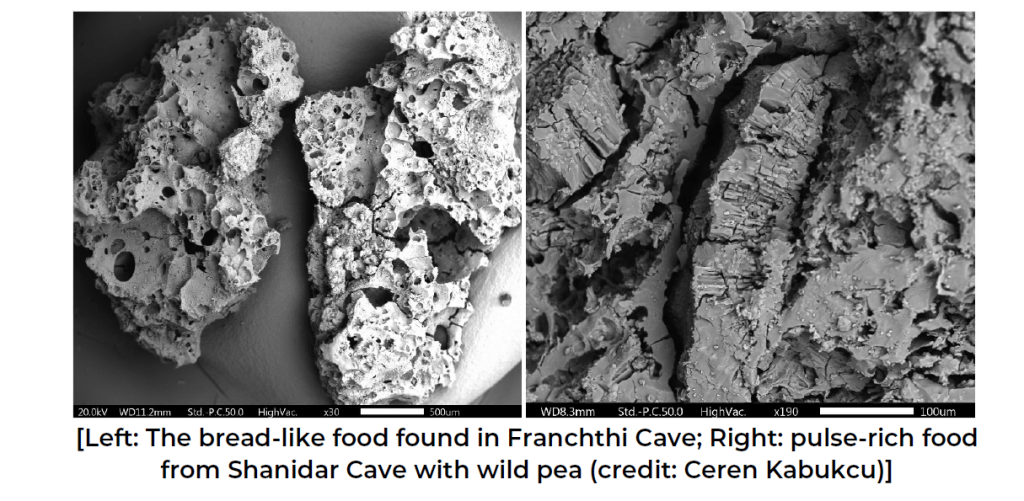

Analysis of some of the oldest food remains ever found (pictured) by a team of archaeologists, led by Dr Ceren Kabukcu at the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology has shown that early modern humans and Neanderthals feasted upon a complex and diverse diet in which plants played a major role.

The research published today (Wednesday 23 November) is the first to show that modern food preparation and processing techniques, and use of a diverse group of plant seeds, were commonplace thousands of years earlier than previously suggested.

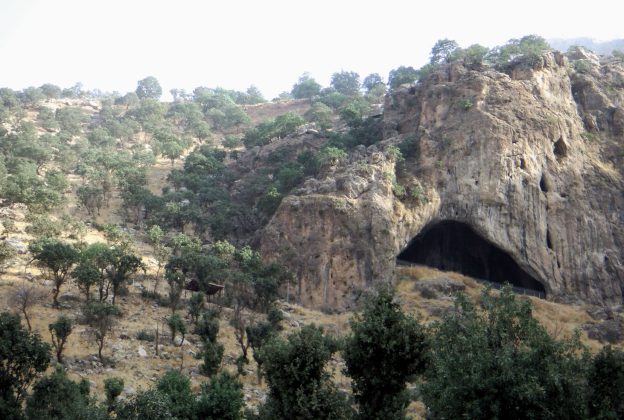

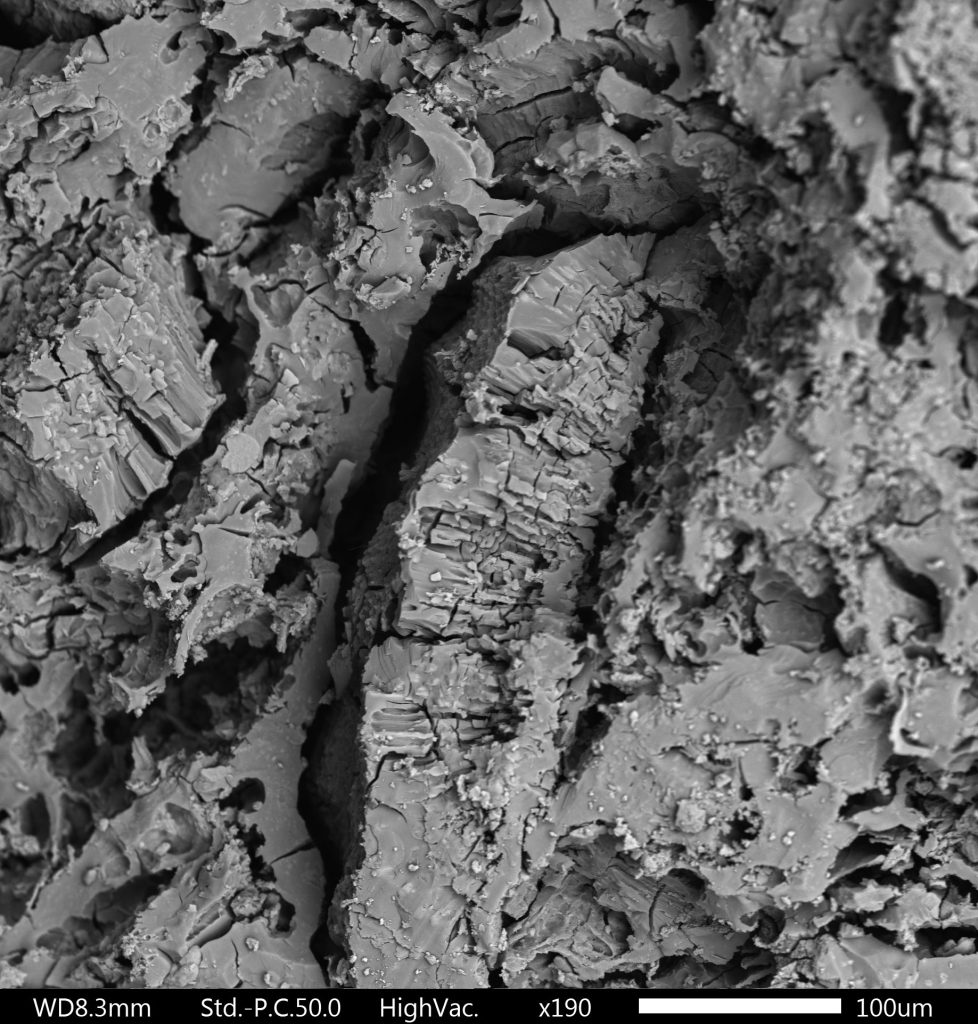

The team used a scanning electron microscope to analyse samples of charred food remains from early modern human (40,000 years ago) and Neanderthal (70,000 years ago) occupations at Shanidar Cave in Iraq, which are the earliest such remains discovered in South West Asia.

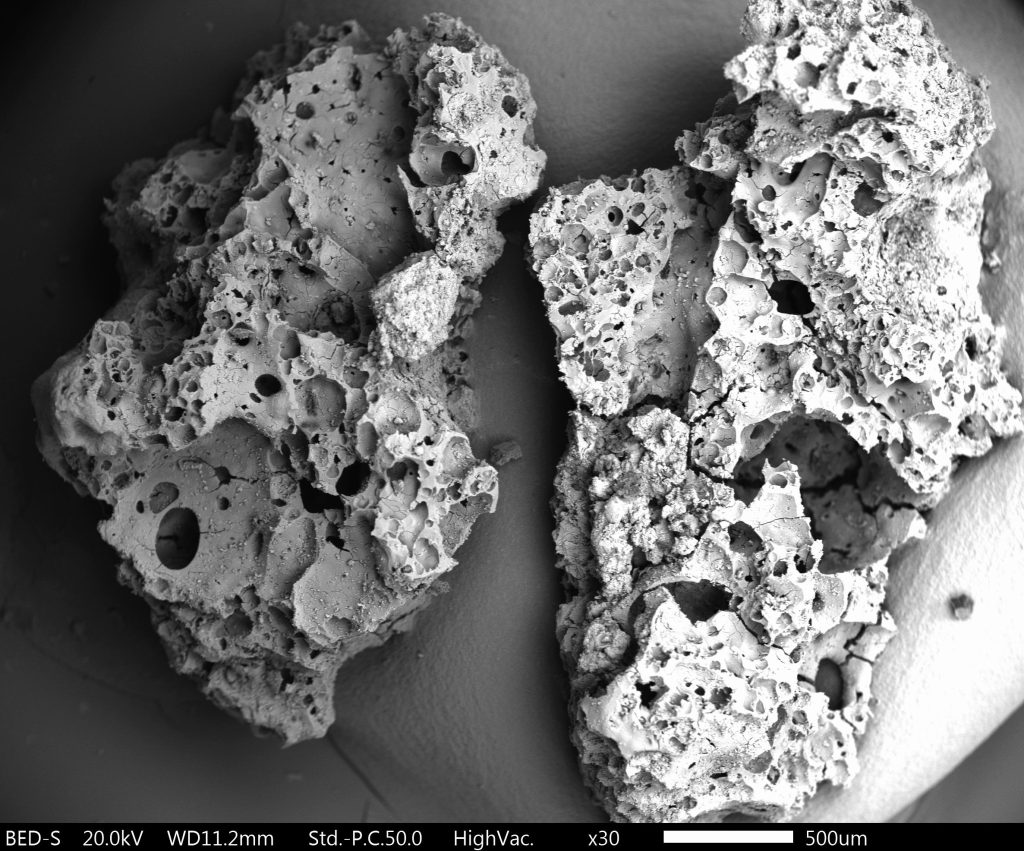

Plant food remains from Franchthi Cave, Greece, are the earliest of their kind discovered in Europe (around 12,000 to 13,000 years old) and include bread-like items resembling flatbread.

The results of these analyses, published in the journal Antiquity, confirm that flavour in food was important from as early as 70,000 years ago and Neanderthal and early modern human cooking often included plants with bitter, sharp, tannin-rich tastes.

From studying the food remains, the archaeologists found that complicated recipes formed part of the Palaeolithic diet, debunking the stereotype that Neanderthals relied on a largely meat-based diet.

The study also identified that Palaeo-chefs used a range of tricks to make their food more palatable. For example, pulses, the most common ingredient identified, have a naturally bitter taste due to the tannins and alkaloids in their seed coats. However, this research found that Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers used complex preparation techniques such as soaking and leaching followed by pounding or rough grinding to remove much of the bitter taste.

Dr Kabukcu said: “This study points to cognitive complexity and the development of culinary cultures in which flavours were significant from a very early date.

“Our work conclusively demonstrates the complexities in the early hunter-gatherer diet which are akin to modern food preparation practices. For example, wild nuts and grasses were often combined with pulses, like lentils, and wild mustard.

“These results represent a major advance over earlier debates about the eating habits of hunter-gatherers, their culinary exploits, and whether Palaeolithic foragers were predominantly carnivores or devoted vegetarians!”

Professor Eleni Asouti, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Liverpool and co-author of the study, said: “Such culinary practices have long been perceived by archaeologists and anthropologists as the hallmarks of Neolithic agricultural societies and the origin of cuisine as we understand it today.

“Our discoveries show that modern cooking techniques have a much deeper and longer ancestry predating the start of agriculture by thousands of years. This research opens new frontiers in the scientific study of the evolution of the human diet.”

You can read the journal article in full here.