by Andrea Livesey, School of Histories, Languages and Cultures

Andrea is studying a PhD on the sexual abuse and exploitation of enslaved African Americans in the lower US South.

“One hundred and fifty years ago the United States was in the midst of civil war, and whilst Abraham Lincoln had just issued the emancipation proclamation – it would still be another eighteen months until freedom finally came for the four million African Americans held in bondage in the United States. The status of these people as ‘non-human’ was so engrained in the American psyche that even the rape of an enslaved woman could only be brought to court if it was considered to be a ‘trespass’ on someone else’s property. On the other hand, a man’s rape of his own enslaved woman could not be a crime – after all, a man is free to do what he likes with his own property. It was this very aspect of enslavement that led former enslaved woman Harriet Jacobs to lament that ‘Slavery is terrible for men; but it is far more terrible for women’.

Ancestry

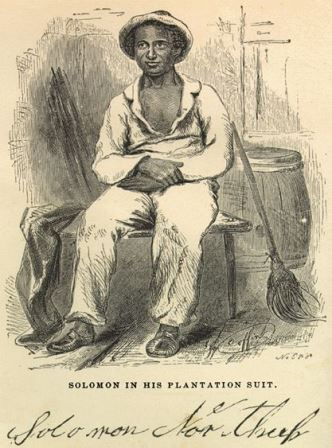

In 2012 genealogists looking into the ancestry of America’s first lady found that Michelle Obama was the great-great-great granddaughter of an illiterate field slave from Georgia named Melvinia who gave birth at age fifteen to a child by a white father, most likely to be the slaveowner’s son. As stories such as Melvinia’s are largely lost to history, it is unclear how many Americans, now living as ‘white’ or ‘black’ have African-American ancestors who endured some form of sexual abuse. What we do know, from the prevalence of references to this in the testimony of former slaves, is that either sexual abuse was a common occurrence or alternatively – the cases that occurred were so traumatic and the fear of abuse so great that these former slaves were unable to omit it from their description of enslavement. One such former slave was Solomon Northup and the film adaptation of his 1853 narrative Twelve Years a Slave, is released in cinemas today.

The film is intrinsically different to both Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained, and Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, despite all three films receiving attention for their release during the 150th commemorations of the Civil War and of course featuring slavery as a key theme. The film may have a central male protagonist, but the director Steve McQueen focuses on the issues of enslaved women in a way only matched by the film Beloved starring Oprah Winfrey and based on the novel by Toni Morrison. Like Twelve Years a Slave, Beloved is based on a real life story, that of Margaret Garner a sexually abused enslaved woman who escaped with her four children before tragically attempting to murder them when she learned that their master had located them. She succeeded in ending the life of her two-year-old daughter. To Garner, after a lifetime of sexual abuse and knowing the fate of her children, death was preferable to enslavement – and infanticide a higher form of love.

Tragedy

This tragedy is echoed in McQueen’s film through the experience of three enslaved women: Eliza, Patsey, and Harriet – all three sexually abused by white men.

First we meet Eliza, who was for nine years kept as the enslaved mistress of her master. She confesses to Northup in the slave pen: ‘I have done dishonorable things to survive…God forgive me’. Eliza knew that she was ultimately her master’s ‘property’ to do with as he pleased and so rather than resist his rape, she chose to submit to his demands in the hope of a better life for herself and her children. But when her master fell ill, she and her two children were sold to local slave traders by the master’s daughter. Eliza’s young child Emily is destined to be sold as a ‘fancy girl’, an enslaved woman, usually light-skinned, sold purely for sexual labour and popular in the New Orleans slave market. The slave trader remarks that there is ‘heaps and piles of money to be made from her, she’s a beauty’. Emily is both the product of white male sexual assault, and its future victim.

Similar to Eliza, Harriet (incidentally without a voice in Northup’s narrative), is kept as the mistress of Master Shaw, a nearby farm owner. She confides that she plays along with the master ‘pantomime’ of affection and fidelity as long as it continues to alleviate her position – the film-goer is aware of the instability of this position. The relationship between US President Thomas Jefferson and his enslaved woman Sally Hemings has often been romanticized as one based on love rather than coercion – yet from the testimony of former slaves we know that enslaved women, such as Harriet, did what they could within the constraints of their gender and status in order to alleviate their position – and after all, Thomas Jefferson did not ever free Sally Hemings. Whilst Supreme Court records demonstrate that many masters did attempt to free their enslaved mistresses after their death, this still demonstrates a clear need to legally control the women in their lifetime.

Abuse

Finally, the slave girl Patsey plays the most prominent role of all the other enslaved women. We are alerted to her youth from her first appearance making corn dolls in the field. Patsey is the victim of both the master and the mistress – the master sexually assaults her and the mistress, instead of sympathizing with her plight, subjects her to psychological and physical abuse. We see here an example of the peculiar extended domestic space and cross-navigational relations of power that slavery created and fostered.

Solomon Northup’s story is not unique. My own research looking at narratives of and interviews with former slaves in the period stretching seventy years after the end of the Civil War highlights the real extent of sexual abuse of women, and the premature sexualisation of girls such as Emily was common. No doubt the sexual abuse of men and young boys by slave holders (male and female) occurred, but evidence is harder to come by. What is obvious is that the psychological pain of men and boys having to stand by and often watch their wives, mothers, sisters enduring punishment and sexual abuse must have been immense.”