Professor Peter Shirlow is Director of the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Irish Studies

I spoke with Martin McGuinness several times, through a mixture of humour and more serious conversation. The first time was when I was up in Stormont and I met him standing alone in a corridor looking tired and frustrated. ‘Have they thrown you out of Sinn Féin?’ I quipped. He smiled, laughed, and retorted, ‘If they had sense they would.’

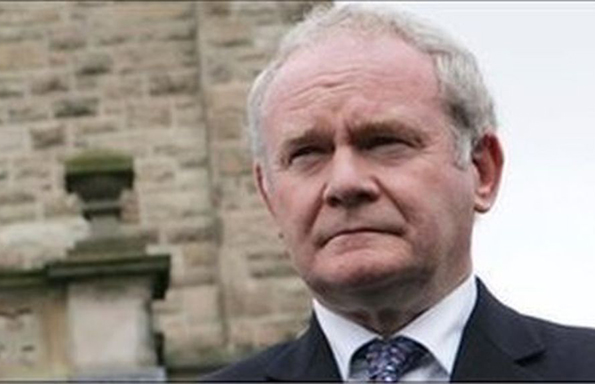

Being up close to a person I had as a child come to loathe, and then knowing him to be human, was in itself a powerful cure to the hatred and fear that dominated so much of life in Northern Ireland. He was without doubt one of those few people you would meet who had leadership qualities. He was patient, firm, comradely and dignified, but as we all know he was a person who had a past. A past that was hard to take for those of us who saw the conflict as dirty and pernicious. Living through that conflict, and then the peace that followed, never removed the anger about it or the desire to challenge the legitimacy casting about it. However, Martin’s leadership and his sense of there being a better and less contested way to cope with sectarian animosity, and shift a divided society into some more agreed future, offered an alternative to wearisome sectarian diatribe and the politics of the never-achievable. I believe he came to that conclusion in the late 1970s when he came to understand that violence was stale, repetitive, and ultimately futile.

He and I were the keynote speakers at Sinn Fein’s “Belfast: A City of Equals on an Island of Equals” event in 2013. Mike Nesbitt then leader of the Ulster Unionist Party had pulled out, and I stepped in to present, from a unionist perspective, concerns about Sinn Féin and the actions of the IRA. A task in itself given there were over two hundred Sinn Féin members in the room. I began my talk by joking that no one else would do it, but that I was not so proud to not feel privileged to be asked all the same. Martin wisecracked: ‘No Pete, we got you because you were cheap.’

Martin listened intently to what I had to say, which was that Sinn Féin had a misguided reading of unionism as merely a sectarian monolith. In his response, there was none of the usual whataboutery, but as he noted: ‘What Pete has said is fair. There is a responsibility upon us to listen.’

As we were relaxing afterwards and chatting about the event, I said: ‘Martin, I respect the leadership you have shown, but will never agree that tying a man to a truck full of bombs or shooting off-duty police officers in the border counties was a war.’ He stared intently at me for a few seconds and then replied, ‘I have thought about that for some time.’ I said, ‘Martin, if that lot out there hear that they will throw you out.’ Laughing, he replied ‘They probably should, they probably should.’

They were wise to never contemplate that.