Tom Phillips is a PhD candidate in international human rights law in University of Liverpool Law School

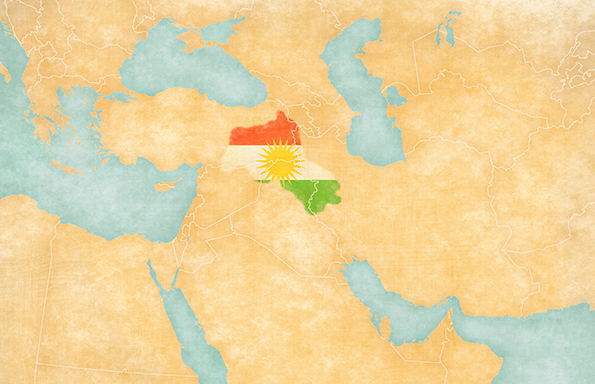

For many Iraqi Kurds, today will be a historic day. They will go to the polling booths to vote for or against having an independent State.

According to acting President of the Kurdistan Region, Massoud Barzani, the outcome of vote (which will, in all likelihood, be a vote in favour of independence) will not lead to an immediate declaration of independence. Instead, Mr. Barzani plans to negotiate with the central government in Baghdad for a period not exceeding two years.

The vote will take place both in the established Kurdistan Region and in the outlying “disputed areas” which are claimed by both Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

State responses

State responses to the planned Kurdish referendum have been predictably negative. The USA, the UK, Turkey, Iran, the Council of the European Union, the Arab League and the Iraqi central government have all publicly opposed the referendum. In fact, the only State that has openly supported the plebiscite is Israel.

Several States express their opposition to the plan to hold the referendum in the ethnically and religiously diverse disputed areas. The Iraqi parliament recently voted to authorise Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to take necessary measures to protect Iraq’s territorial integrity, and to dismiss the Kurdish governor of Kirkuk.

Of course, as Mr. Barzani points out, the legitimacy of the referendum does not come from foreign diplomats. One source of legitimacy that he and other authoritative figures claim is the right of self-determinaiton.

Self-determination and secession

Self-determination can plausibly be understood as a participatory right that applies to territorial units.

In the Kosovo case, the International Court of Justice ruled that international law does not prohibit declarations of independence. But it chose not to consider the important question of whether self-determination entails a right to unilaterally declare independence (i.e. without the permission of the host State).

We do not yet know what the KRG plans to do if it cannot reach an amicable agreement with Baghdad, but it does not seem likely that international law recognises a right to unilateral secession. The respected international lawyer James Crawford points out that “Since 1945, no State which has been created by unilateral secession has been admitted to the United Nations against the wishes of the government of the predecessor State.”

The court in Kosovo also touched upon the claim that self-determination entails a right to unilateral secession in cases where a group has been subjected to gross human rights violations or is subsumed under an unrepresentative government.

The court found that those taking part in the proceedings expressed “radically different views” on that question. Since only 11 out of 36 participating States supported the claim, it seems unlikely that there is a customary law right to secede even under such parlous circumstances.

Negotiated self-determination

In 1998, the Canadian Supreme Court in Reference re Secession of Quebec argued that Quebec was not entitled to unilaterally secede from Canada, whether or not pursuant to the right of self-determination. Instead, the Court ruled that the Canadian authorities were under an obligation to give “considerable weight” to the views of the population of Quebec on the independence question and to negotiate with them in good faith.

Mr. Barzani already plans to exercise the right of self-determination in this way, but the case suggests that a failure to reach agreement with Baghdad will not necessarily entitle the KRG to go its own way.

Of course, one must bear in mind that Iraq is not Canada. It is not at all clear that Iraq’s Prime Minister is free to even consider allowing Kurdistan to secede, given the currently existing regional dynamics.

Some procedural problems

Discussions around self-determination often focus exclusively on possible end-states, such as independence. But it also important to focus on the process through which the end state is reached.

Although the KRG is, by regional standards, fairly democratic and open, there are several shortcomings.

The independent news channel NRT TV has been prevented from airing programs critical of the referendum and journalists have not been completely free to express their opposition to it.

There are also serious problems in the disputed areas. Matthew Barber, who has considerable on-the-ground experience, notes that the minority communities in the disputed areas reject being annexed to the Kurdistan Region and reject being ruled by Mr. Barzani’s KDP. Many of them complain, with some justice, about the bullying of the population in areas where they live.

Such behaviour only serves to undermine the overall legitimacy of the referendum – at least in the pertinent regions. Whatever the future status of the Kurdistan Region and its outlying areas, some kind of arrangement will be needed to accommodate the various minority communities who also have an interest in self-determination.

In that respect, Mr. Barzani’s promise that a future Kurdistan will be an inclusive “homeland for all” based on decentralisation and federalism is a welcome development. But it looks like there is a long way to go before some minority communities are convinced.

Whatever happens after the referendum on 25th September, the Kurds are no longer an invisible nation. Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey should seek ways of dealing with that new reality by accommodating their demands for self-determination, whether in the form of statehood, enhanced autonomy, some form of advanced cultural rights regime, or a combination of these approaches. The advancement of democracy, human rights, and peace in the region depends on it.

A longer version of this article is available here: http://www.nrttv.com/EN/birura-details.aspx?Jimare=7655