Picture: Sander Lamme

Dr Mike Jones is a Senior Lecturer in the University of Liverpool’s Department of Music

Today (Thursday 26 September 2019) marks the 50th anniversary of the release of the Beatles album Abbey Road. Essentially, this was their final album – the final release, Let it Be, consisted of material recorded before the Abbey Road sessions.

Abbey Road is notable for a host of reasons: firstly, it was a return to a reasonably ‘collective’ form of recording. Once the Beatles had ceased touring and settled themselves into the Abbey Road studio, individual recordings had increasingly become ‘solo’ projects; the double-album The Beatles (better known as ‘The White Album’) exemplifies this, but the process is much in evidence on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and even on Revolver. Ultimately, the experience of working together again could not halt the fragmentation of the group. In this way, the album stands as a poignant exercise in ‘what might have been’ – it is a high quality record which shows that the Beatles had kept on going forward in terms of their originality despite the deepening rifts between the group’s members.

Secondly, Abbey Road contains two very notable George Harrison songs: Something and Here Comes the Sun. Something was released as a single and topped the US charts. There were many subsequent cover versions (making it the second most covered Beatles song after Yesterday) and it is, at the time of writing, their most streamed song in Spotify. Something earned high praise from Frank Sinatra as one of the great love songs, and the two Harrison tracks suggest another ‘what might have been’ had his song-writing been more encouraged by Lennon and McCartney.

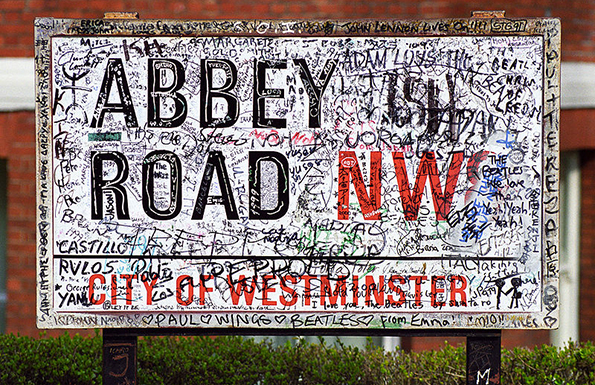

Thirdly, the albums cover photograph, although a very simple one when compared with the elaborate Sgt. Pepper’s sleeve, has gone on to become one of the most enduring images of the Beatles. If a picture is worth a thousand words then this one seems worth a novel, or at least a dramatized documentary – the four figures look very distinct from each other and not especially happy, yet the regular ‘bars’ of the zebra crossing enforce a uniformity on them. Here are the Beatles as ‘the world’ had experienced them, in step with each other as they had been from the day Ringo joined to their last ever paid gig at Candlestick Park in San Francisco on the 29th August 1966. Yet another ‘what might have been’.

The lack of smiles in the Abbey Road photograph tells its own story – the divisions had become unhealable, and it is again poignant that the furthest they could be persuaded to travel together to be photographed was, quite literally, just across the road from the studio in which almost all of their most famous recordings had been made.

Liverpool musician Thomas McConnell has just finished recording his album at Abbey Road and, in conversation, reported that some of the instruments played by the Beatles remain at the studio – including the piano Paul McCartney played on Fool on the Hill and the celeste George Martin played on Baby Its You. From a distance these seem to be ghostly relics of a remarkable past, but musical instruments are, depending on your perspective, either obliging or promiscuous, those in question were as likely to be played on Hole in the Ground by Bernard Cribbins as on Goldfinger by Shirley Bassey (both George Martin productions) – they do not ‘belong’ to the Beatles and the individual Beatles do not belong to our fond memories of them.

Tape and film fix sounds and images but these never capture all the relationships in play at the moment of that fixing. Where the Beatles Abbey Road is concerned, songs as relaxed as Here Comes the Sun, as potent as Come Together and as surreptitiously barbed as You Never Give Me Your Money, have confirmed the Beatles as a lasting cultural phenomenon, even when the group itself was in the process of not lasting as the unit that had inspired so many.