Costas Milas is a Professor of Finance in the University of Liverpool’s Management School

As the coronavirus escalates and public worries about the outbreak sky-rocket worldwide, the attempts by central banks to unleash a co-ordinated response have fallen alarmingly flat.

America’s central bank, the Federal Reserve, led the way on March 15 by slashing the US headline interest rate to zero (between 0% and 0.25%) and launching a new US$750 billion (£620 billion) round of quantitative easing (QE), the policy that aims to shore up the financial system by creating new money to buy assets like government bonds. This supposed “bazooka” came less than two weeks after the Fed cut rates from 1.75% to 1.25% and subsequently made US$1.5 trillion in additional liquidity available to US banks.

The Bank of Japan, which has been pursuing QE continuously for a decade, has announced it will double its programme for buying stocks to ¥12 trillion (£93 billion) a year, while also increasing its purchases of shares in property funds and corporate bonds. These followed comparable moves by the Bank of England, European Central Bank and most recently the People’s Bank of China.

World markets were deeply unimpressed by this huge intervention. The Dow Jones plunged 13% on Monday March 16, its second worst ever daily performance after the Black Monday crash of 1987, and many markets are falling again on March 17. During previous crises, such coordinated moves have seen markets rise or at least stop falling so sharply.

Policy limits

Part of the problem, as outlined in research I co-authored with Chris Martin, a professor at the University of Bath, is that QE is fairly ineffective in the current environment of extremely low interest rates. Notably, both the UK and US governments’ costs of borrowing for ten years are extremely low. This means that injecting more QE in an attempt to lower the country-specific costs of borrowing, which is in turn intended to pass through to lower corporate borrowing, has just about reached its limits.

It has not helped that ECB president Christine Lagarde made a “dangerous slip” a few days ago when she said it wasn’t the bank’s job to narrow the differences in borrowing costs between different eurozone countries. She was comparing Germany and Italy, in a statement that seemed totally at odds with her predecessor Mario Draghi’s loud commitment to do “whatever it takes” to prop up the struggling Mediterranean countries during the eurozone crisis in order to save the euro.

Alexandros Michailidis

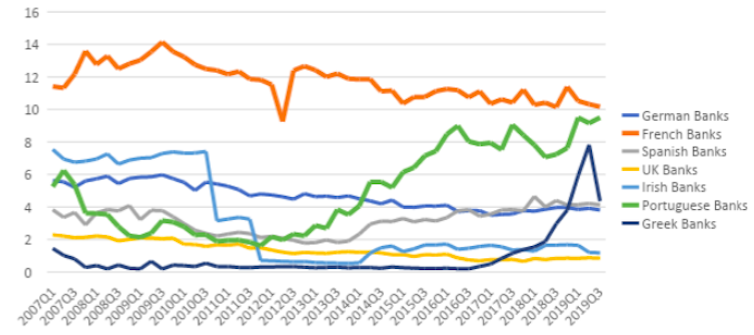

Though Lagarde and her chief economist later clarified that the ECB would fight against fragmentation in the eurozone, the costs of borrowing for Greece and Italy have risen sharply. As well as inflicting further jeopardy on these countries at a time when the coronavirus is causing chaos in Italy, many northern European banks are significantly exposed to Italian private and public debt – per the graph below.

Interestingly, after Draghi’s original “whatever it takes” statement in 2012, almost all European banks, particularly Portuguese ones, increased their exposure to Italian debt. French banks have maintained significant exposure ever since, while Greek banks should also worry because they have become more exposed in the past three years or so.

Exposure to Italian debt as a % of total global debt exposure

Mark Carney, the former governor of the Bank of England, recently mentioned that banks, unlike during the 2008 financial crisis, can be “part of the solution” this time around, having been strengthened to cope with crises. To some extent, this may be right. But if Italy is not supported by the ECB, Europe’s banks will start to have a problem.

What next

To mitigate this crisis, there are five things that can now be done to help.

1) Governments must hammer together a co-ordinated plan to boost spending. This is likely to be more effective than tax cuts in stimulating the economy in the short run. Such moves should build on the interventions we have seen from the likes of the UK and New Zealand already. Co-ordination is important, as echoed by the head of the IMF, because countries trade with each other. If one does “enough” to restore its supply chain and demand but others don’t, we will all still be stuck with the problems in supply and demand that are driving the economy down.

For instance, governments can support those who have lost their jobs or are quarantined. This is arguably more pressing in the UK, where unemployment benefits are much lower as a percentage of previous income than the OECD average. Another good move would be to increase wages for those on the front line, such as nurses, whose starting salaries took a hit in real terms after the last financial crisis.

2) Tax cuts are still an important stimulus in the medium term, so we need to see them too. We should significantly cut VAT to stimulate consumer demand around the world, with particularly aggressive cuts from countries hit hardest by the outbreak. Governments should slash corporate tax rates to help prevent companies from collapsing under the weight of the crisis. The OECD average VAT rate is 19.3% and the average corporate tax rate is 23.5%. If every country slashed both rates by five percentage points, it should help.

3) Closing European borders is not the answer. To see Germany, the power engine on the continent, doing this for all but commercial traffic feels like a large step in the wrong direction. It risks introducing extra frictions in trade that will add to the economic downturn. This will make it harder to coordinate economic action and must be reversed. To misquote Dante, the darkest places in the economic hell will be reserved for those who refuse to coordinate policies with other countries at a time like this.

4) To mitigate the mounting crisis in Europe, Christine Lagarde must keep re-iterating that her policy is a continuation of Draghi’s policy. This will re-assure the markets, which have a very short memory and like it when policymakers repeat robust messages.

5) While the virus is still rampant, there is a limit to what can be achieved by cutting taxes and interest rates. Only by getting it under control will we see the confidence boost that will bring consumers back to spending and allow healthy workers to return to full capacity. It goes without saying that this means implementing the best mitigation measures and pushing to create a vaccine as quickly as possible.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For all the latest news and insight from the University of Liverpool, follow @livuninews