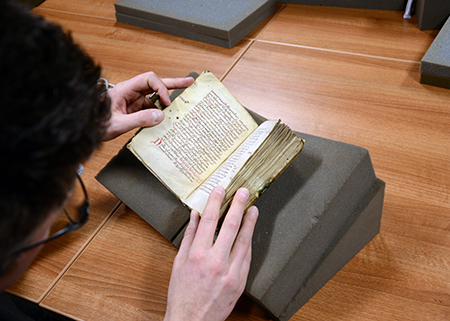

Dr Erik Kwakkel with Gregorius’ De cura pastorali – now thought to be almost a thousand years old

A book in the Sydney Jones Library can now claim to have been made almost a thousand years ago – and take the title of oldest book in University of Liverpool’s collection – after a visiting expert redated it using new developments in the field.

Dr Erik Kwakkel, of Leiden University in the Netherlands, was visiting the University’s Special Collections and Archives to deliver a workshop and talk to postgraduate students on medieval manuscripts.

‘Cultural residue’

An expert in the fields of palaeography and codicology, Dr Kwakkel attempts to uncover what he terms the ‘cultural residue’ of works, to gain an insight into their age and possible use. He explores manuscripts by examining aspects not central to the text itself; such as book chains, marks from candle wax, reader annotations or the type of material the work is written on.

The visit was organised by Dr Sarah Peverley, of the University’s School of English. Dr Peverley said: “The work Dr Kwakkel is doing with manuscripts is revolutionising our ways of thinking about them. His research on the ways in which the features of a medieval book can be tracked and recorded will allow scholars to date manuscripts more precisely and replace the intuitive judgments that palaeographers traditionally use with hard evidence.”

Dr Kwakkel leafs through the text with, from left, Dr Sarah Peverley and Medieval and Renaissance Studies MA students, Kate Watkins, Seamus Cartmell and James Duffy

Dr Kwakkel was given the opportunity to explore the extensive collection and determined that a copy held of Gregorius’ De cura pastorali was not made in the 13th Century, as originally thought, but actually dates back an additional 100 years – making it the oldest in the collection.

Erik said: “We can see that this book is a little bit older than thought. But what makes it more significant is that it still has its original bindings. These are extremely rare in the Middle Ages, particularly when we move back in time from the 13th Century to the 12th Century. This is the most important item here. When you have the binding, you can see what it looked like in the Middle Ages. We have the full picture and we can see the book like a medieval person did.”

Among those attending the workshop were Medieval and Renaissance Studies MA students, Kate Watkins, Seamus Cartmell and James Duffy. Seamus said: “It’s interesting to think that it’s not necessarily what’s in the document, as much as its physicality – we have to listen to what it says. The book is a silent witness.”

On a mission

Erik told students that the presence of a chain on a book, or even the remnants of a chain, revealed that it was stored in a public place. Any annotations or marginalia were also likely to have been produced by readers across the ages, and not by the monks who originally produced each work.

He added: “I do this because I am on a mission. The medieval manuscript needs a bigger audience, much bigger than it has, and the next generation needs to be inspired. I do feel that graduate students need to feel there is something still to be researched.”

To further this aim, both Erik and Sarah are active on twitter @Erik_Kwakkel and @Sarah_Peverley

The oldest book in University of Liverpool’s extensive collection, complete with bookworm holes

Dr Peverley added: “We have a wonderful collection of medieval books at Liverpool, which we use all the time for teaching, so it’s great that the team in Special Collections is supportive and allows us to bring in guest speakers to work with such precious items.”

Find out more about our Special Collections and Archives here: http://sca.lib.liv.ac.uk/collections/index.html