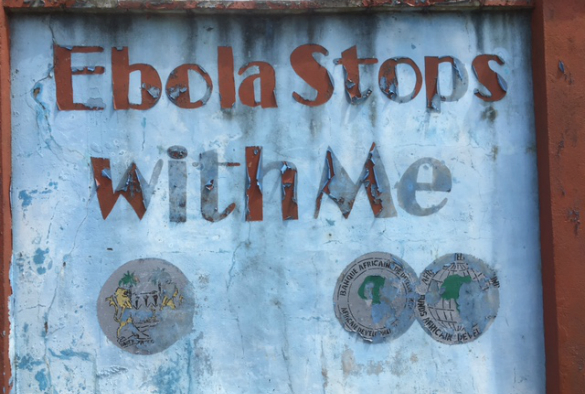

A faded Ebola warning sign in Freetown, Sierra Leone

Dr Georgios Pollakis is a Senior Research Fellow at the University’s Institute of Infection and Global Health. He recently travelled to Freetown in Sierra Leone as part of his research into the Ebola virus.

There were two sets of scientists and doctors that worked hard to halt the devastating 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak – those that travelled immediately to West Africa to treat victims and implement public health strategies aimed at halting the epidemic, and those, like me, that remained working in the lab and on computers to understand the epidemic as it unfolded. The aim for all however, was ‘never again’.

One only realises the full extent of the epidemic on their first trip to a now Ebola-free region, where everyday life was stunted and which now slowly begins to return to normality. On my first day in Freetown, when I spotted a continental electrical plug stuck in a British socket, I said to myself that maybe I should downgrade my expectations a little. When I sent a text to my companion back in Liverpool the response was, “Can you do that?” As the days went on though that changed and my initial expectations about how far the city had come since the epidemic ended were more than surpassed.

The outbreak may be over, however the fading warning signs around the city are still evident, and are a constant reminder of devastation caused and the countless people left grieving the loss of their loved ones.

‘Never again’

During my visit I met doctors, scientists and students all with the same aim – ‘never again’. Each wanted to address their own questions and to understand what happened, including myself and other Liverpool colleagues who studied the virus during the outbreak and continue to do so now.

Dr Georgios Pollakis (left) in the lab in Sierra Leone.

It has become very clear to all that some of the answers to these questions may be held by the biology of those who lived – the survivors. They themselves know this and I was astounded by their support of those continuing to carry out research. Scientists such as Brigadier General Dr Sarh and Major Dr Sevalie and others at the Military Hospital 34 (MH34), one of the many Ebola Treatment units, are to be thanked for their work.

The doctors, the nurses and the rest of the staff at MH34, the blood bank and the members of the national ethical committee expressed their thanks for sharing with them our efforts to understand the virus, all trying to find a way for the ‘never again’. The health-sciences students at the University of Makeni equally astonished us with the pertinence of their questions and their commitment to their studies.

Dr Janet Scott and I are now back in Liverpool with renewed enthusiasm to continue investigating the immune parameters in Ebola survivors’ blood – enthusiasm injected by the doctors and the survivors themselves during our two-week stay in Sierra Leone. It was two most gratifying weeks, both in the lab and the seminar room. While giving my presentations I could not help but wonder, “How many survivors do I have in front of me, I hope I am not disappointing them”. I hope there is a sentiment that their contribution to our laboratory work has been fruitful.