Kieran Maguire is a football finance expert in the University of Liverpool’s Management School

With football financial issues being in the public eye as a result of Neymar’s record transfer from FC Barcelona to Paris St. Germain, has football priced itself out of being a family game?

It is generally accepted that the Premier League is the most financially successful global football competition.

In 2016/17 the Premier League had eight of the top twenty income generating clubs in the world, matches are sold out (attendances were 98% of capacity in 2016/17), and there are waiting lists for season tickets at many clubs.

Attending a single match, which used to be a case of walking up to the turnstiles and walking into the ground, can be both difficult to organise, but also expensive for an individual or family.

Income from fans represents one strand of revenue for clubs, the other two being broadcast rights from TV and radio, and commercial/marketing income.

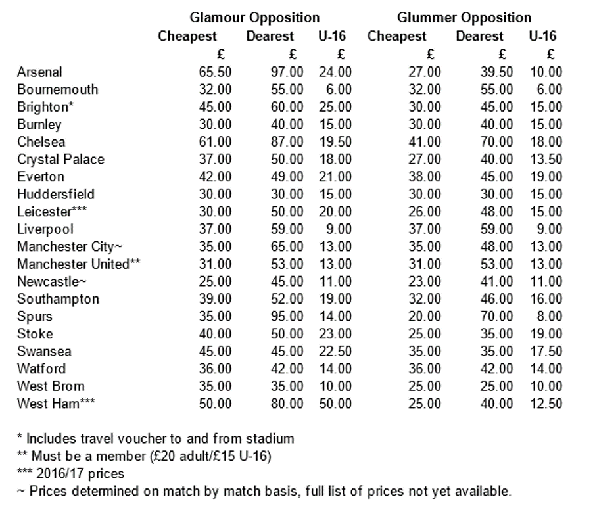

We have looked at prices being charged by clubs for the forthcoming season to see different strategies being employed in terms of clubs in the Premier League.

How much do tickets cost?

Some clubs are transparent about ticket prices for individual matches, whereas others have not yet published details, or keep them behind a membership wall.

Clubs also have different strategies depending upon the extent of the fanbase, and how tolerant fans are of paying different prices to watch different opposition.

These clubs therefore have categories of prices (Newcastle, according to local sources, charged six different prices the last time they were in the Premier League, for example).

We have therefore contrasted prices charged when the opposition is a glamour club (Manchester United, Liverpool, Chelsea etc.) or a small club, such as Crystal Palace.

Some clubs (Liverpool, Burnley, Bournemouth, Huddersfield for example) charge identical prices regardless of the opposing team.

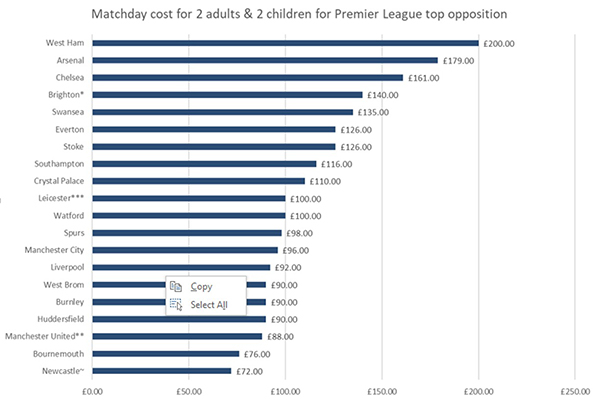

So how much does would it cost two adults and two children to watch a match against the likes of Liverpool or Manchester United?

So how much does would it cost two adults and two children to watch a match against the likes of Liverpool or Manchester United?

The range is considerable (and this is of course before taking into consideration transport, merchandise, food and drink etc.) ranging from £72 to £200. West Ham United, owned by novelty salesmen, playing in the London Stadium (which hosted the 2012 Olympic Games and 2017 IAAF World Athletic Championships), are by far the most expensive.

For fans of away teams there is some solace. Away ticket prices in the Premier League have been capped at £30 each, to encourage fans to travel to watch their team.

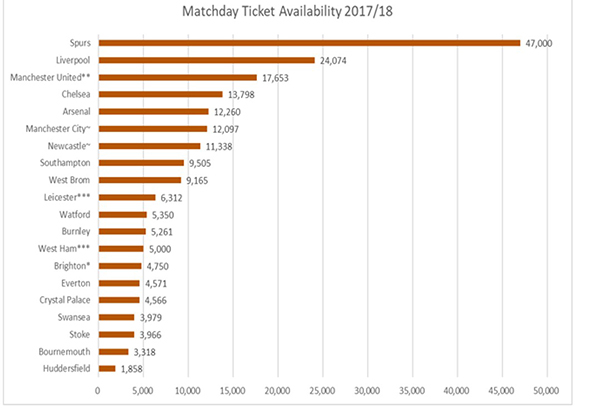

How many tickets are available?

It could be of course that some clubs will charge a lot because tickets are scarce, as so many are sold to season ticket holders, and therefore they can justify high prices to irregular fans and football tourists.

This does seem however to penalise those who, perhaps by work, family or financial reasons cannot acquire a season ticket.

Many clubs are coy about the number of tickets available on a match by match basis, but the latest information, based on ground capacities, seats allocated to away fans and published season ticket sales is as follows:

The figure for Spurs is distorted this season because the club is playing its home fixtures at Wembley Stadium whilst White Hart Lane is being redeveloped to increase its capacity.

The figure for Spurs is distorted this season because the club is playing its home fixtures at Wembley Stadium whilst White Hart Lane is being redeveloped to increase its capacity.

It could also be argued that some of the above tickets may be allocated to corporate boxes, and so less are available to regular fans.

The table does highlight that some of those clubs with a very large fanbase restrict the number of season tickets sold to increase the chances of other fans seeing their team at the home ground.

This might initially appear very noble, but from a financial perspective these irregular fans are also more likely to buy merchandise when they visit the stadium. This means their total spend at a match is considerably lower than that of a season ticket holder.

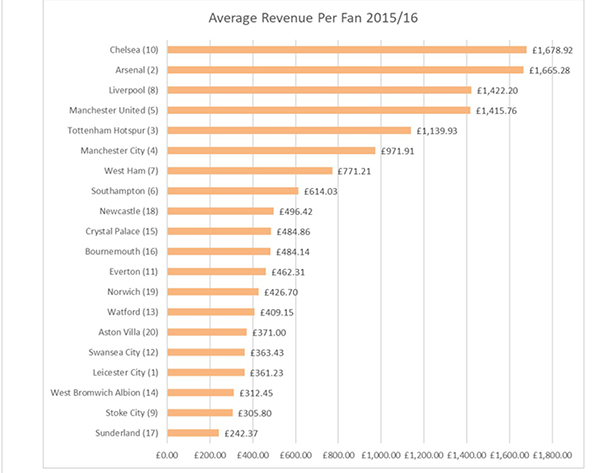

This is borne out by looking at the average matchday spend (which does include corporate boxes and hospitality for most clubs) for clubs in the Premier League in 2015/16, the most recent year for which we have data (figures in parentheses after the team name represents the final position that season).

The above shows the impact of being in more affluent locations, such as London, cup success (Liverpool had thirteen home cup games in 2015/16, for example) and the ability to extract extra income from non-season ticket holders.

Conclusion

Football has reached a ceiling in terms of the prices charged to many who love the game and want to see their team.

Anecdotal evidence of falling viewers for subscription sports channels suggest that clubs cannot squeeze fans, both armchair and terrace, any further.