Kieran Maguire is a football finance expert in the University of Liverpool’s Management School.

What do Paris Saint-Germain and Manchester City have in common? They are both owned by Middle Eastern wealth funds, they both spent over £200 million in the Summer 2017 transfer window, and both have previously been found guilty of Financial Fair Play (FFP) overspending by UEFA in 2014, with resultant fines (mainly suspended), squad and transfer limits imposed.

Both clubs have now also been subject to accusations of breaching FFP in the Summer 2017 transfer window, with PSG doubling the world transfer record with Neymar, and City spending over £200 million. La Liga, the Spanish football league, has reported both clubs to UEFA in relation to their recent transfer activity.

This seems initially harsh, as both clubs made a profit in the most recent set of accounts, and are not the highest paying clubs in terms of wages, compared to other clubs in the Premier League.

Why does FFP exist?

Michel Platini announced FFP to great fanfare in 2010, claiming “this approval is the start of an important journey for European football’s club finances as we begin to put stability and economic common sense back into football. I thank all the stakeholders who have supported this along the way”.

Sounds very noble, but a quick look at the rules revealed that FFP was a profit (or in the case of many clubs, a loss) based metric.

As anyone who has worked in finance will know, bankruptcy arises because of a lack of cash, not profit. If you don’t have the cash to pay your suppliers, wages or bank loans the business faces the risk of administration.

Profit is an artificial measure, full of judgement, opinion and far more easily manipulated than cash, so it seems odd that UEFA would go down this particular route.

Further analysis indicated that many of the established ‘big’ clubs were very keen on FFP. Why was this the case?

Prior to the newly monied clubs arriving on the scene, the makeup of Champions League places was constant. Between 2004/5 and 2009/10 the same four clubs (Manchester United, Liverpool, Chelsea and Arsenal) all qualified for the Champions League by taking the top positions in the Premier League.

The broadcasting and commercial benefits of Champions League qualification gave these clubs a financial advantage that made it very difficult for other teams to challenge for a top four position, and so an effective cartel arose, with (almost) guaranteed Champions League appearances.

The arrival of ‘new money’ in the form of Abu Dhabi and UAE ownership changed the cartel at the top of European football.

FFP was an attempt to prevent the rise of another PSG or City, by ensuring that new owners could not inject huge sums into clubs to ‘buy’ domestic success and the attached Champions League qualification.

What are the rules?

Under the initial UEFA rules clubs must aim to break even (i.e. costs should not exceed income) over a rolling three-year period. The rules have been slightly relaxed so that now clubs can make an FFP loss of €30 million over the same period.

FFP losses are not the same as the figures in the accounts. This is because some expenses, (youth development, women’s football, community projects and infrastructure costs) are excluded from FFP costs. Therefore, a club could make a €30-40m accounting loss and still break even for FFP purposes.

Can the rules be circumnavigated?

Simply put, yes. There is scope for clubs to artificially increase income (PSG currently have the third highest commercial income of any club, exceeding that of Real Madrid and Barçelona, despite their lack of Champions League success or global fanbase) by signing deals with ‘friendly’ parties, perhaps related or controlled by the club owners, at above market rates.

For example, a sponsorship deal that might normally be worth €10m might be signed for €40m.

Manchester City signed a naming rights deal in 2011 with Etihad Airways for a reported £400 million. City are owned by Sheik Mansoor of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Etihad Airways is the national air carrier of UAE. There’s nothing wrong legally with signing such an agreement, but it led to accusations of ‘financial doping’ from the likes of Arsene Wenger.

UEFA do have the right to adjust these numbers to a ‘fair’ (i.e. market) value, when investigating FFP breaches, but it is difficult to ascertain what a fair figure should be.

As well as inflating income, clubs could manipulate costs. A player could sign a contract with a club and be paid ‘only’ £50,000 a week, but simultaneously sign an agreement to be a sporting ambassador for a friendly party for a further £500,000 a week. This would not go through the club books, and so would be ignored for FFP purposes.

Multi-club ownership, where an organisation owns many football clubs, also allows some scope for moving costs.

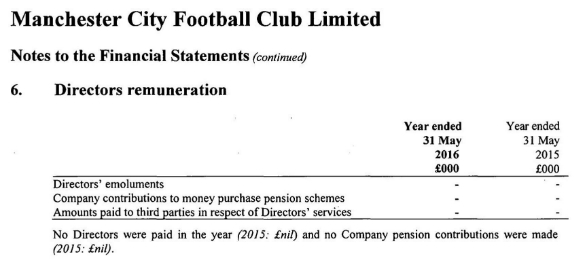

For example, a look at directors’ wages for Manchester City Football Club Limited shows the following:

Manchester City football club are 100% owned by City Football Group Limited, who also own clubs in Australia and the USA (and have just taken part ownership of Girona in Spain), and they show the following in relation to directors pay:

Manchester City and PSG do have financial advantages over other clubs as a result of being owned by sovereign wealth funds. These advantages have been used to offset the monetary head start of pre-existing ‘big’ clubs, some of whom themselves have benefitted from institutional and state support historically.

There’s nothing that ‘old money’ dislikes more than ‘new money’, and this is as much as anything else the motivation behind the accusations made by La Liga in relation to the two Middle Eastern owned clubs.

I wouldn’t recommend buying any 2017 Spanish wine, as it appear to consist of some sour grapes.