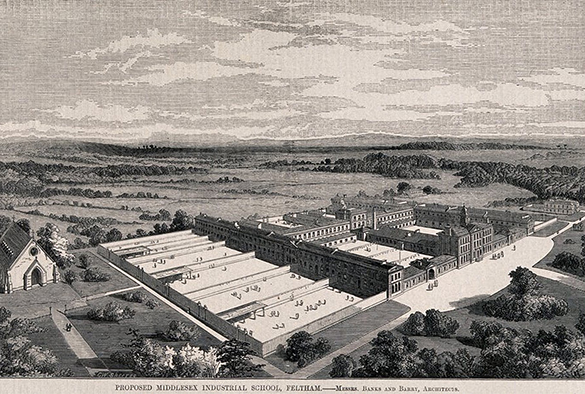

Plans for an industrial school in Feltham, England. Charles William Sheeres, Banks and Barry via Wellcome Images, CC BY-SA

Barry Godfrey is Professor of Social Justice in the University of Liverpool’s Department of Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology

Victorian institutions designed to reform delinquent or vulnerable children were much more successful than today’s youth justice system in assisting children to recover from troubled starts in life, according to new research my colleagues and I have published.

From the 1850s, the government, charities, and faith communities constructed a rudimentary welfare net for children who had committed crimes by sending them to reformatories or military training ships. Children who were at risk of committing crimes because of neglectful or criminal parents were sent to industrial schools rather than workhouses because they were deemed at risk of becoming delinquent.

Our research revealed that approximately 9,000 children a year were admitted to industrial schools from the mid-1850s to the end of the 19th century, and another 1,000 a year to reformatories, according to the annual judicial figures that my colleagues and I analysed.

The average reconviction rates for these institutionalised children were low. Taking the whole of their lives into consideration, only 22% of children who were in reformatories and industrial schools committed crimes in their adult lives following release – and only 2% committed more than one crime after release. Victorian and Edwardian children who had either committed offences or were deemed at risk of committing offences seem to have had better outcomes than today’s children, where the reconviction rate is much higher.

Today, 40% of juvenile offenders in England and Wales reoffend within just the first 12 months of their release from custody.

Why did the Victorians succeed?

Both the reformatory and industrial school systems of the 19th century were orientated towards equipping children for work. Children were taught employment skills suitable for the Victorian marketplace. Stockport Industrial School, for example, trained children for the textile trade, and had relationships with local employers who employed children directly after they left their institution.

Bradwall Reformatory in Cheshire gave their children the sort of skills required for the local agricultural economy. They too were employed as soon as they left the reformatory – many had already served work placements with their future employers.

Reformatories and industrial schools then maintained contact with the children, enquiring how they were getting on in the world of work for years after they were released. Our research found that many children wrote letters back “home” to the institutional alma maters when they became adults.

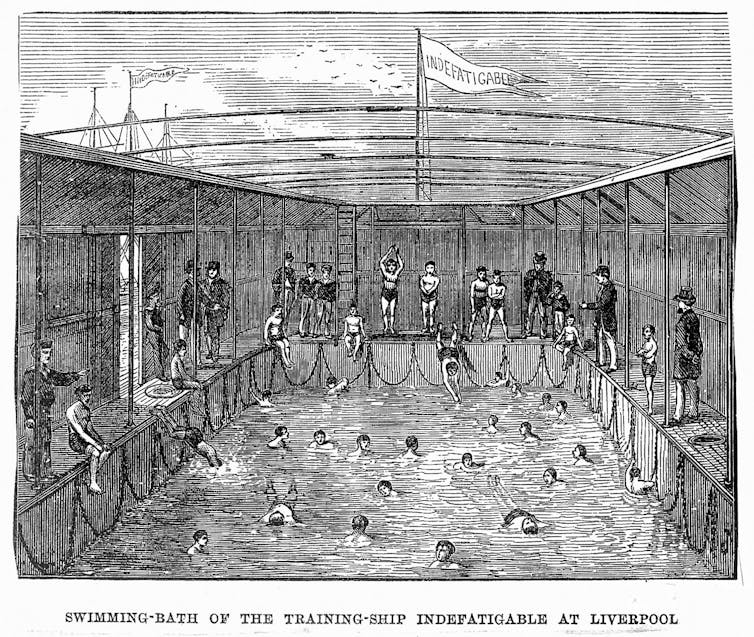

Wellcome Images, CC BY-SA

Institution staff provided a family life for children, many of whom had not experienced settled and loving family environments before they entered the institution, and formed lifelong relationships with their former charges. In 1896, eight-year-old William Brown had been found living in a house frequented by prostitutes. He was sent to Stockport Industrial School to stay there until he was 16.

After leaving, Brown enlisted as a “band boy” with the 21st Lancers but was discharged just one year later, despite his character being recorded as “very good” by his regiment. He then picked up a number of temporary jobs (barman, mechanic, chauffer, waiter) but found his feet in 1910 when he started work as a photographer’s assistant in London.

Commenting on the regular reports and photographs he sent back to Stockport Industrial School, the staff noted that he was “a fine young man, quite a swell”. He emigrated to Canada and found employment as a photographer, and married. Some 30 years after leaving Stockport, he brought his wife to the UK to visit the school. As with many children who went on to lead decent lives, a good relationship with institutional staff during and after their period in care was critical to them staying out of the courts and gaining useful employment.

Violent and abusive places to grow up

We know, of course, that many children suffered horrendous violent and sexual abuse. In 1910, the publication John Bull, in an article entitled “Reformatory School Horrors”, alleged that three boys had died as a result of excessive punishments and neglect. The newspaper particularly condemned the “cold water” punishments of “malingerers”, one of whom “was taken out into the courtyard in wintry weather, when he had 52 buckets of cold water thrown over him”.

Other punishments included birching and caning, and deprivation of food and clothing. Children at one of the other institutions my colleagues and I studied, the Akbar Training Ship, moored in the Mersey, often mutinied and rebelled against their brutal treatment.

Victorian society may have seen harsh treatment as a part of bringing reform and a successful life to institutionalised children. The measures of success were different, and the aspirations of the children in Victorian institutions may also have been different. We can imagine that any kind of “British Dream” that would have made sense to Victorian and Edwardian children would have meant a safe and secure residence, continuity of some form of employment, and their children having a better life than they had had.

![]() The reformatories and industrial schools set up by the state and charity sector during the Victorian period ensured that most of the children who passed through them did actually achieve these modest dreams. For those who were irrevocably damaged by their early institutionalisation, of course, their childhood experiences may have haunted them into adulthood.

The reformatories and industrial schools set up by the state and charity sector during the Victorian period ensured that most of the children who passed through them did actually achieve these modest dreams. For those who were irrevocably damaged by their early institutionalisation, of course, their childhood experiences may have haunted them into adulthood.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.