Dr Michael Ellington is a Lecturer in Finance and Costas Milas is a Professor of Finance in the University of Liverpool’s Management School

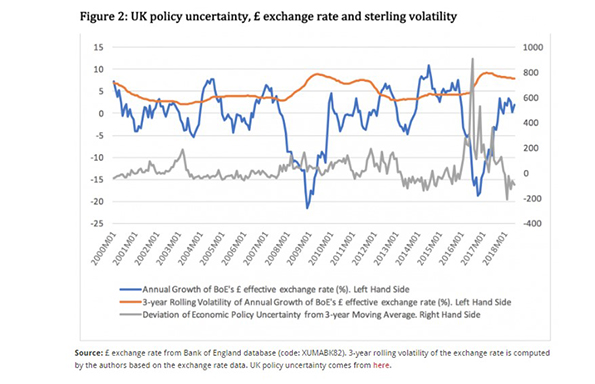

The ongoing political turbulence over Brexit two years on has not stopped the UK economy from growing in a fairly robust manner. Indeed, brand-new monthly GDP data released by the ONS for the first time in July 2018 indicate that our economy is growing slightly better than previously thought. Figure 1 plots together annual GDP growth (based on the latest release of quarterly GDP data) and inferred annual growth based on the first-ever release of monthly GDP data.

As can be seen from Figure 1, the monthly data paint a much rosier picture since the EU referendum. All this implies that if the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) members decide to trust the brand-new monthly GDP data, it is more likely than not that they will raise the Bank’s policy rate in early August. Unless, of course, Boris Johnson and other pro-Brexit MPs have other ideas about our government’s fate.

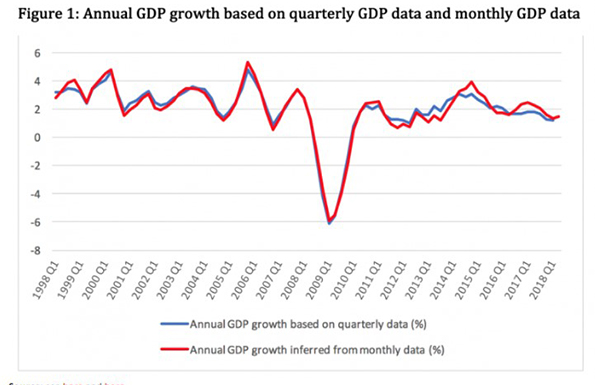

In fact, the very resignations of David Davis and Boris Johnson have the potential of destabilising the economy if one (or both) ex-ministers decide to ‘challenge’ Ms May’s leadership. Alternatively, our EU trading partners have the potential to slow down our economic prospects if they decide to challenge the ‘soft’ Brexit approach agreed by our government during the recent Chequers meeting. Indeed, either Boris Johnson or Michel Barnier have the potential of adding to policy uncertainty which, in turn, will trigger a big drop in the pound’s exchange rate and a big rise in the pound’s exchange rate volatility.

Historically, sharp drops in the sterling’s exchange rate and rising exchange rate volatility go hand in hand with peaks in policy uncertainty. This is indeed documented by Figure 2 which plots deviations of UK policy uncertainty (measured by newspaper articles from The Times and The Financial Times discussing economic policy uncertainty) from its 3-year Moving Average together with the annual growth of sterling’s effective exchange rate and the 3-year rolling exchange rate volatility.

As can be seen from Figure 2, rising policy uncertainty fuels exchange rate volatility and both of these ‘economic ills’ eradicate any economic benefits stemming from the weaker exchange rate. In the presence of rising policy uncertainty and exchange rate volatility, UK exporters will consume themselves into spending considerable time and effort to hedge against exchange rate risk rather than pursuing profitable investments in export-related trade. All this will lead to higher inflation, therefore undermining the ability of consumers to support our economy through additional spending; and slow down investment planning therefore questioning the ability of our economy to grow stronger.

Watch out for the next move of our Conservative Brexiters and the response of EU’s Chief negotiator Michel Barnier to Ms May’s ‘soft’ Brexit approach. In other words, an interest rate rise in August is far from a done deal and very much dependent on our internal politics as well as the response of EU policymakers to our government’s Brexit proposals.