Dr Michael Ellington is a Lecturer in Finance and Costas Milas is a Professor in Finance in the University of Liverpool’s Management School

Prime Minister Theresa May has warned “it’s either my [Chequers] deal or no deal”. With betting odds implying a probability of 62.5% on no deal being reached before April 1st 2019, one way of looking at the impact of such an outcome is to consider its consequences in terms of an economic policy uncertainty shock. There are good reasons why policy uncertainty affects the economy. Policy uncertainty motivatesagents to delay investment and hiring decisions, and so leads to a decline in investment employment and total output. Further, under these conditions, monetary policy becomes less effective. This is because agents tend to postpone decisions until more precise information becomes available, and this cautiousness makes them less responsive to changes in the economic environment, including the interest rate. Last but not least, credit rating agencies respond by downgrading the credit profile of countries hit by rising policy uncertainty.

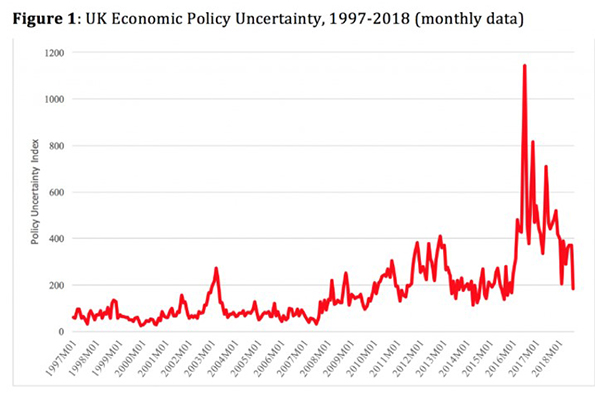

We measure economic policy uncertainty based on articles from The Times and The Financial Timesregarding policy uncertainty. We count the number of articles containing the terms uncertain or uncertainty, economic or economy, and one or more policy-relevant terms. Following from the EU Referendum result, policy uncertainty recorded an unprecedented spike in June 2016 (see Figure 1). Since then, policy uncertainty has somewhat receded; nevertheless, it remains elevated compared to its pre-2015 levels.

Source: http://www.policyuncertainty.com/index.html

In new research we assess the impact of economic policy uncertainty on the effective exchange rate and interest rate differentials between the UK and our main trading partners (namely the Euro area and the US) prior to, during, and in the aftermath of the EU Referendum. This is done in the context of so-called time-varying models which are flexible enough to track the changing nature of key economic variables over time. Two key results emerge.

First, the influence of a policy uncertainty shock to the interest rate differential between the UK and our trading partners had been more persistent and contractionary in the run up to the referendum. For a given value of our trading partners’ policy rate, a shock to economic policy uncertainty a year before the referendum remained prominent 20 months after the shock was observed.

Second, the depreciation of the sterling effective exchange rate was substantially more persistent and contractionary in June 2016 than the year prior to and following the vote. In June 2016, a shock to economic policy uncertainty caused the exchange rate to depreciate by 15.8% in the year after the shock occured. Notice that in the year after the referendum the actual sterling depreciation was 9.3%.

Our results highlight the importance of economic policy uncertainty for monetary policy stance as well as for exchange rate movements. What our findings also emphasise is that, in order to hinder the influence of policy uncertainty, the UK needs to agree on a trade deal prior to its departure from the EU.

Mark Carney has warned MPs that “[f]rom a monetary perspective, we would look to do what we could to ease that [no-deal] scenario but there are limits to what we can do,”. Under the assumption that the impact of an economic policy uncertainty shock during June 2016 is a ‘best-case’ scenario of what might happen to monetary policy stance and exchange rates, the absence of a trade agreement looks set to yield further depreciations of the pound relative to leading currencies, together with a sharp cut in the Bank’s policy rate and another round of quantitative easing. Loosening the monetary policy lever through quantitative easing will also look to hinder possible downgrade pressures on the UK’s national debt, something that will most certainly be transmitted to the private sector. In other words, a no-deal Brexit will push the Bank of England to the limit.