University of Liverpool archaeologists carrying out an Iron Age experiment in Wales have instead uncovered the ‘Plastic Age’ – the plastic dominated archaeology left behind by modern society.

The researchers were investigating the remains of reconstructed Iron Age roundhouses built on the original sites at Castell Henllys Iron Age fort.

These had been open to visitors for over 30 years, hosting hundreds of school days out, before being dismantled at the end of their life. It was hoped excavating these structures would shed light on the decay process and how it impacts archaeological preservation.

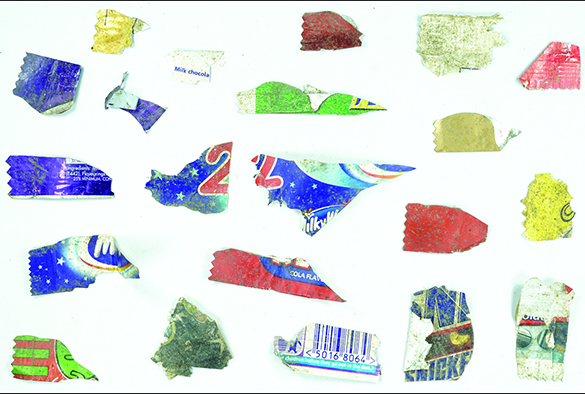

However, the more dramatic discovery, published in the journal Antiquity, was the sheer amount of plastic dug up. Despite the fact the houses were regularly cleaned to maintain the illusion of an Iron Age environment, the excavators found over 2,000 plastic items.

This far outweighs the replica prehistoric items used at the site or even other traces of modern life.

Lead author, Professor Harold Mytum, in the University’s Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, said: “We had not anticipated the large amounts of rubbish – mainly plastic – that was deposited, even though the houses did not look untidy.”

The sheer number of the finds prompted the researchers to join with other scholars arguing we are now living in the ‘Plastic Age’.

Even in this relatively isolated and well-maintained space, enough plastic was trodden into the earth or lost in dark corners to dominate the archaeological record of the houses.

What would such finds tell an archaeologist in the future? It turns out the record from the houses was mostly driven by children, whose packed lunches often feature a lot of plastic which needs to be torn to get at the contents.

Professor Mytum said: “Plastic spoons, straws, snack bar wrappers and cling film, and even labels from apples, were all very common finds.

“Schools and families need to think about how they can make pack lunches that are more environmentally friendly.”

The archaeologist of the future would also have trouble directly dating many of these finds. Whilst many items once had best before dates, the process of tearing them open meant surprisingly few remained readable.

Meanwhile, the researchers in the present are hoping to use these discoveries to investigate how and where plastic accumulates to reduce the amount incorporated into the ground.

They are also working with Pembrokeshire Coast National Park to use these finds to better educate the public and raise their awareness of these environmental concerns.

Ultimately, Professor Mytum and his team hope the Plastic Age might not last millennia like the Iron.

He added: “With many initiatives now pushing to switch from disposable plastic and plasticised items, this may be a narrow, but archaeologically distinctive chronological horizon.”

Read the full paper, The Iron Age in the Plastic Age: Anthropocene signatures at Castell Henllys published in the journal, Antiquity. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.237